Today, we’re joined by Bobby Fijan. He’s a co-founder of the American Housing Corporation, a startup building housing for families in cities. A burning question motivates his work: How do you make cities places where families can live and thrive? He has a new report out with the Institute of Family Studies looking at what families really want from their apartments.

This is a pretty self-indulgent episode for me. I live in Brooklyn with my wife and two-year-old, and we’re expecting our second kid. We want to stay in the city — it’s where our life and community are, and where we’ve put down roots. But the classic route for people like us is to move out to the suburbs once the family grows. I hoped talking to Bobby would help me avoid that fate.

Bobby argues that the best ideas for family-friendly housing aren’t new. Pre-war apartments in American cities look a lot like what he’s advocating for. We’ve done this before, and we could do it again.

We discuss:

How the financial crisis fuelled a boom in studio apartments

Why did apartments get so much smaller after 2008?

Why are most two-bedroom apartments designed for roommates?

What do families actually want in a floor plan, and why don’t developers build it?

Whether upzoning can help

Thanks to Harry Fletcher-Wood and Katerina Barton for their judicious transcript and audio edits.

For a printable transcript of this interview, click here:

Bobby, I hope I’m not putting too much pressure on you in this conversation, to save me from despair that I’ll have to leave NYC.

I hope not.

Since the Great Recession, there’s been a huge change in the American housing market. More and more of our new housing is apartment buildings instead of single-family homes. Why is that?

Not only are apartments a greater share of housing relative to generations past, but this is concentrated in areas where apartments were already being built — cities and the areas directly around them. An apartment is only going to go in an area where land values are slightly higher. A single-family house is more likely to go in greenfield development.

I was not involved professionally in real estate prior to the Great Recession. But afterwards — in 2009–11 — if you had a project called a “condo project,” the barriers placed on you by lenders were very high. They required things like pre-sales of units in order to make the loan. Whereas for an “apartment project” — the same building, volume, and space — they were going to allow that to just go forward.

This is something that doesn’t get telegraphed enough to intelligent laymen: how much the policies of the agency lenders — Fannie Mae and Freddie Mac, in particular — drove development and rehabilitation of apartment stock. Like a lot of government programs, it turns out that there are corner solutions. Apartments ended up being one of those corner solutions. Then smaller and smaller apartments, or apartments that had a greater share of one bedrooms and roommate-oriented two bedrooms, started being built in significantly greater numbers, accelerating from 2009 until today.

Was that because of regulation, like Dodd-Frank in 2010? Or was it this “once bitten, twice shy” dynamic — post the housing collapse, lenders are more nervous about non-standard apartment types?

There was so much inventory that had been built for sale, slowly working its way through the market. That same time period is when the private equity firms started entering in a big way, buying single-family rentals. That hadn’t existed before, but there was a huge amount of stock that ended up getting purchased by Invitation Homes and other firms. It was difficult to justify how you could make the numbers work to build when the market was so saturated.

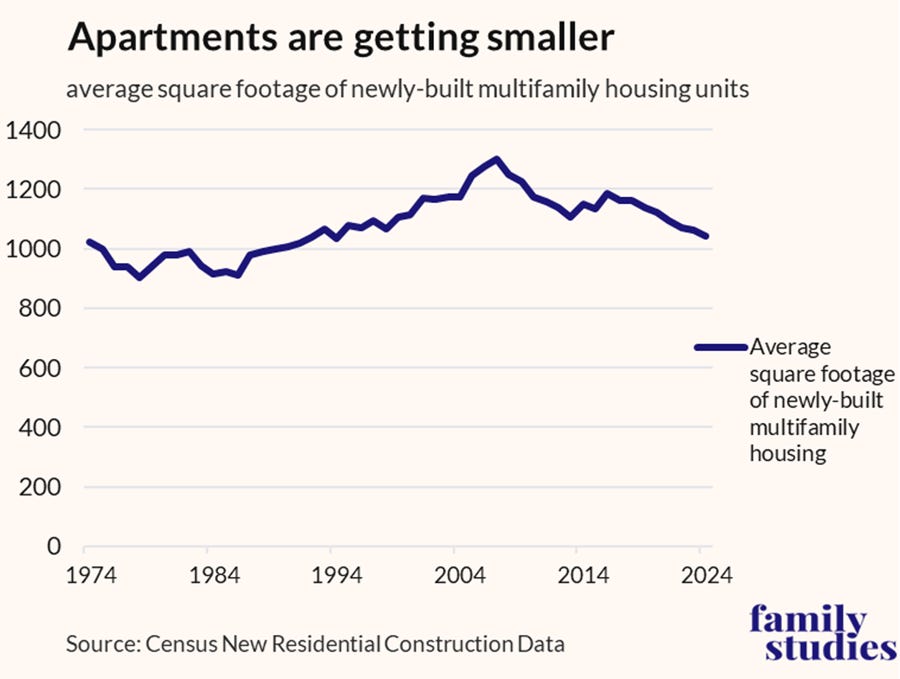

You have a new paper out with the Institute for Family Studies — full disclosure to readers, my wife is a fellow with IFS. This chart from the paper shows the average square footage of new multi-family housing. It peaks in 2008-2009, and it’s been dropping since. In 2024, the average square footage of a new apartment is around 1,000 square feet. That’s equivalent to the average square footage in 1994.

What’s going on?

The share of apartments that are studios is dramatically increasing. There are more people moving to the cities and to slightly denser areas. People would rather live on their own than with roommates. Before 2000, if you look at Austin, studios weren’t built that much. Now, as high as 20–30% of new products are studios. So the greater share of the overall mix being 400, 500-square-foot units drives the average down quite a bit.

That’s one thing I don’t think gets picked up enough in housing statistics. People look at raw numbers, rather than at “typology.” The average unit size is shrinking anyway. It becomes easier to understand when you say, “We didn’t build studios, and now we build tons of studios.”

But you’ve also pointed out that the larger apartments we build today are less good for families. It’s not just that there are fewer two- or three-bedrooms than there used to be. You’re also saying, “The two- and three-bedrooms that exist often are not designed for families.” What does that mean?

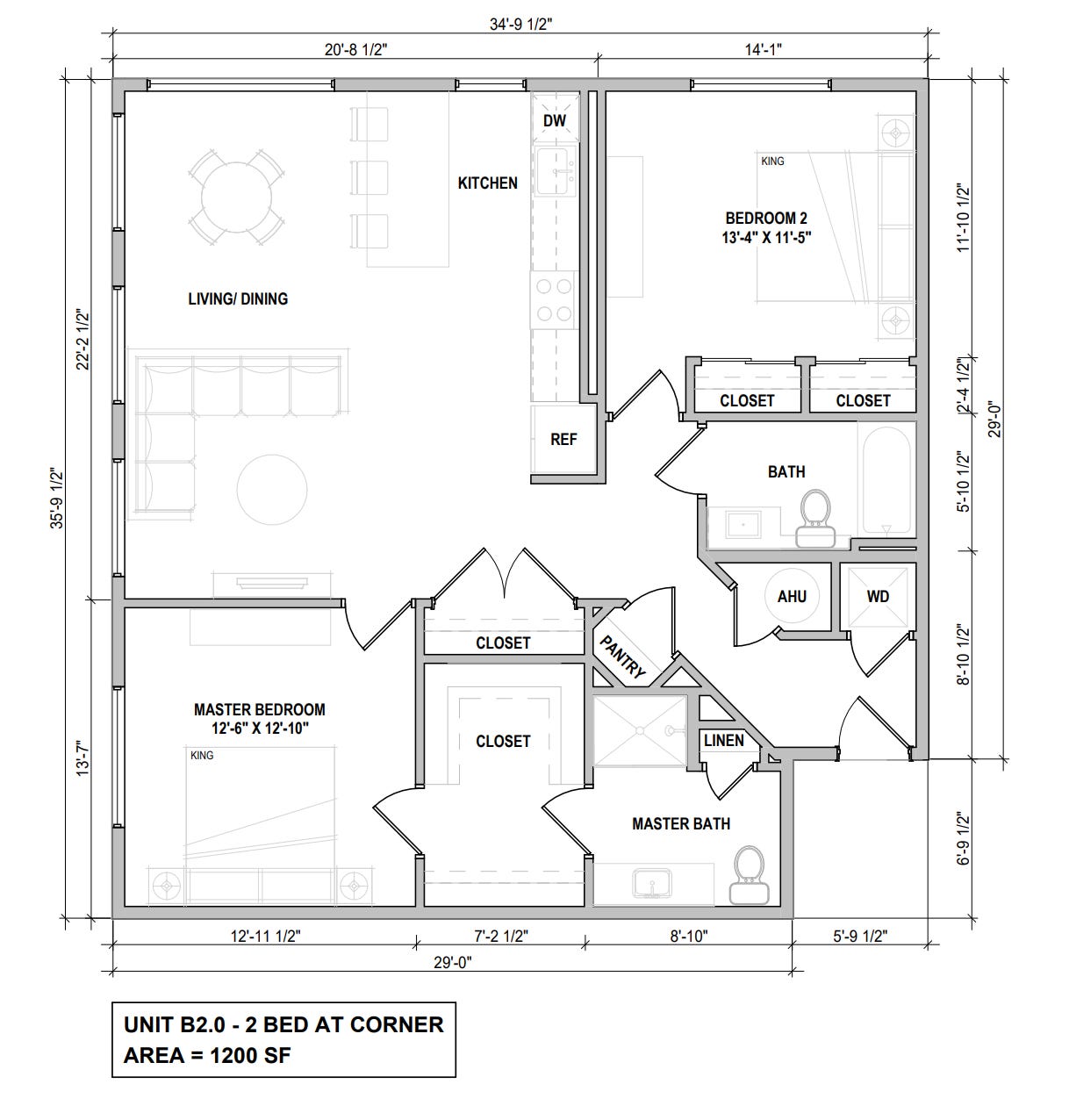

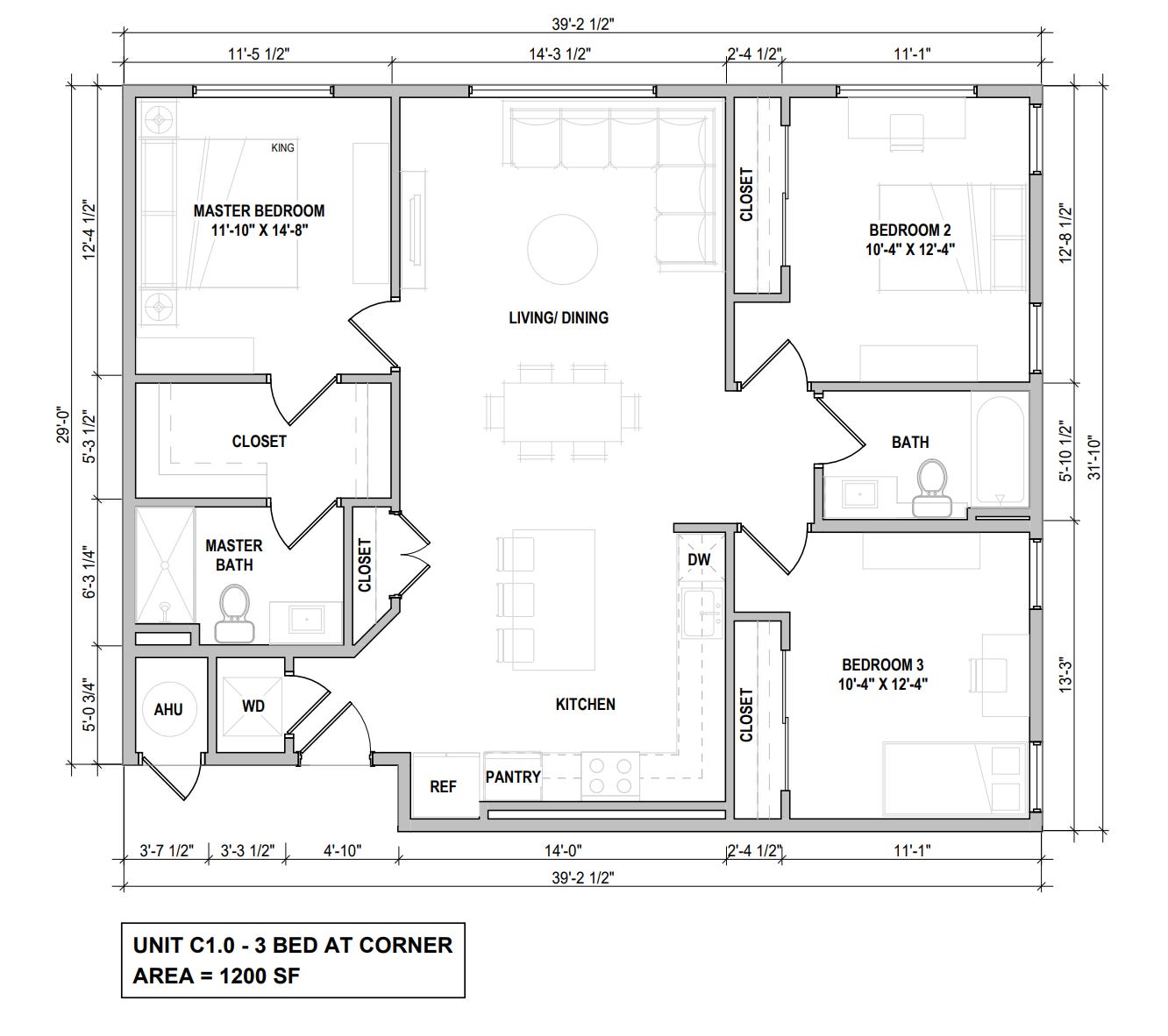

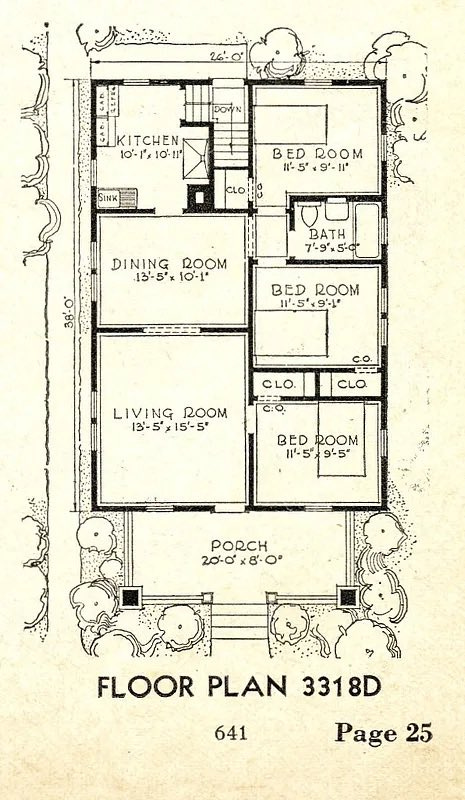

I would encourage everyone to look at the floor plans, and it’ll become abundantly clear. If you were to look at a typical two-bedroom apartment in D.C., Philadelphia, Boston — even Austin, Dallas — it will look the same in most of those markets. It has two equal-sized bedrooms with direct access to a bathroom and large closets. That’s an ideal layout when what you’re trying to solve for is maximizing rent, based on studios. Let’s say the studio rent is going to be $1,000. To share a bedroom, it’s going to be slightly cheaper than that — 80–90%. That still puts two-bedroom rents at a fairly good number based on the overall size.

There was no poor intent on anyone, but the main reason they’re not designed for families is that they were designed for roommates. Since the Great Recession, many more young people have moved into the cities. The market is reacting to the fact that people want new apartments and they want to share.

What would that same two-bedroom look like if it were built for a family?

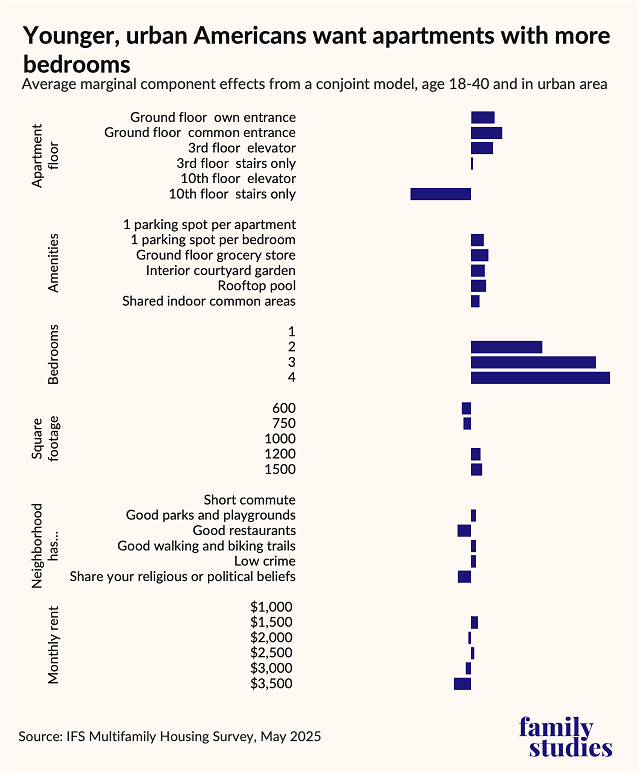

That is one of the things the IFS study looked at. We showed survey respondents a two-bedroom that had two equal-sized bedrooms, and then one that had a larger bedroom for parents and two smaller rooms, one that had a window and one that did not. Families, or people who were open to having children, had a dramatic preference for the same square footage with the extra room. That’s the general principle of what it would look like: more open space, smaller secondary bedrooms.

The other key point, within a fixed square footage, is fewer bathrooms than bedrooms. Through the ‘70s and ‘80s, two-bed, one-baths were a fairly commonplace unit type. Since the ‘90s, and particularly the 2000s, two-bedroom, one-baths are not built. It’s all two-bedroom, two-bath.

Not only have apartment sizes shrunk, but the ratio of bedrooms to bathrooms has also shrunk. The excess living space has also decreased, because bathrooms are regulated by turn radius and other fixed things, more than other rooms. You can’t get them much smaller than 5x8 feet, especially if they have a shower or a tub. That usable square footage shrinks even more.

By turn radius, you mean there needs to be a certain amount of room in a bathroom for it to be up to code?

The turn radius is specifically designed for a wheelchair. Whether or not the unit is fully-compliant with a wheelchair, one of the bathrooms needs to be partially available for wheelchair users. It means that bathrooms need to be larger, and it’s the reason that bathrooms are larger in the US than in Europe.

When you ask people who are open to having kids about the features in a floor plan they value, they’re willing to give up other things to get extra bedrooms. What are they willing to give up?

Bedrooms are far and away the highest asset they want — over everything else, including yard, price, and space. We could not find one asset that they preferred more.

When you think about it from first principles, you want another place to put your child. Everyone who’s lived in the city knows that parents are resourceful. In New York, I knew plenty of people who used a second bathroom, a closet, or put up a temporary wall. You figure out some way to get your child in their own space. Obviously there are some people who do co-sleeping, but by some point, you want the kids to have their own little area where they can hit their bedtime at 7:00 PM, and the parents don’t have to go to sleep at the same time.

I got breakfast with a buddy this week who has a daughter, and she sleeps in the tub of the second bathroom. He said it works great. They don’t turn on the faucet.

In your survey, the only apartment feature people hated more than they wanted the extra bedroom was a tenth-floor walkup.

I didn’t say it partly because that one was absurd, but that’s right.

As an aside, do those exist? Are there tenth-floor walkups today in America?

There might be. They’re not allowed to be built, so new housing can’t do that. Once you get up to four stories — three in some places — you have to put in an elevator. If it exists, it is a vestige of an earlier time. You might find it in some part of a city that’s over 140 years old. But it would be very unusual.

When my wife was pregnant with our first, we had to move out of our Manhattan one-bedroom. I visited a bunch of listings, and there was a place in Chinatown that I loved, but it was a fifth-floor walkup. I was trying to rationalize in my head, “Can I sell this situation to my pregnant wife?”

If there’s one thing I want the company to do, it’s to build products that prevent the exact situation you described. I want people to be able to have a kid and stay. That is what the extra room gives. When people have to immediately say, “Now I’ve got to go find a new apartment so that we aren’t moving and having a baby at the same time,” that is when the city loses too many people.

There’s a lot of different things that the city needs to fix. But the key part about making cities better for families is that they don’t have to be fixed for a newborn. Babies are small. All they need is that extra space, and then you can figure things out. That’s not to say there aren’t other things that are as annoying as the fourth-floor walkup. Anyone who uses the subway who has a kid knows there’s no elevators that go to any subways, and the ones that do, you probably don’t want to take them — either they’re unreliable or unsafe. So you’re carrying the stroller up and down four flights of stairs anyway: which was good for me; it was less good for my wife.

In the study, you have people look at a bunch of floor plans and pick, “A or B, which do you prefer?” One of the big takeaways is, “If you want to build housing for families, the open floor plan has got to go.” It’s funny because I think of the open floor plan as a feature of modern suburban family life: mom can see the kids from the kitchen and we’re all in the same space, even though it’s much bigger. But in an urban context, you say, get rid of it.

You have design features that have been imported from other housing types. Go look at any 750-square-foot one-bedroom in AvalonBay or Toll Brothers. The kitchens are enormous. They’re enormous for all floor plan types, even studios. Every single one of them has a full-size kitchen range. No one ever cooks there. It’s not like anyone is hosting Thanksgiving in their 550-square-foot studio. Yet the kitchen is still 14½ feet long.

That is driven by institutional standards: with more apartments under management, it’s easier to build and manage one type of thing. Look at pictures of a kitchen with a huge island — that makes sense in a 3,400-square-foot McMansion. The kitchens are about the same size in the city, which makes no sense, but it’s what’s done.

When you say that’s driven on the institutional side, do you mean it’s easier to build that big boat of a kitchen, or it’s easier to build it at scale?

Anyone who takes a first-principles approach and walks into a studio would say to themselves, “Why is the refrigerator or the range in a studio the same size as in the three-bedrooms?” It does not make sense.

Why do they have four burners, and the fridge is taller than me?

Exactly. So why is it? Housing costs elsewhere are going up. People are looking to reduce costs as much as possible. In the United States, we have not been able to manage modularized construction as well as other places. The way that we can marginally reduce construction costs is through standardization at the building level. So when someone builds a 250-unit apartment complex, they want to say, “We have 15 floor plan types, 3 one-bedroom types, and these kinds of kitchens.” It becomes an easier way of designing and constructing a limited number of things on site. That’s what keeps similarity there.

It has become politically convenient to talk about units being held vacant. We obviously agree that no one is holding market-rate apartments open on purpose in order to make money because they don’t. They lose money. There are some parts of it that are a teeny bit true, in that optimized price theory would say that if you were at 100% occupancy, the prices are too low. In an efficient market, there should be some level of vacancy, because it means that you’ve raised it enough such that there are some empty units. That’s trying to be very generous to those [who believe in this critique].

But the other part of vacancy, which actually adds 1-2%, is — think through the process when someone gives notice. In most markets, when someone gives notice, it’s usually 60 or 90 days in advance. The property manager gets that notice and then decides what date they are going to place that unit available for rent. The thing that cannot happen to a property manager is that someone’s lease date comes and the unit isn’t ready. That either means you have to put them up at a hotel, or there’s a tremendous amount of management hassle.

How does an enterprising manager handle that? They say, “We do not know the state of that unit until the day it is vacated. Are we going to try and back-to-back every unit? That would be insane.” So they generally push it out one or two weeks. There might be some that they turn over right away, where they’ve gone into the apartment in advance, but you still won’t know exactly. Someone gives notice on July 1st, you say, “The unit is available July 15th,” but someone can move in between the 15th and the 30th. So the vacancy might end up being a month.

Here’s the other part that becomes interesting: how that plays into studios. Studios turn over at about double the rate of a three-bedroom. That’s because people who are 22–26 are going to be changing jobs more; they might want to upgrade to something else. The more that units churn, the more building occupancy is going to decrease, due to the logistics of needing to change the carpet, or fixing the doors.

That all comes back around to the kitchen question: building managers use their vacant units — they know they’re going to have a few — as storage for their other units. If you need to get an apartment ready right away, and the handle on the fridge is broken, you go to one of your vacants and you pull it. As an efficient manager, you want to have similarity within all appliances, to be able to swap things out as much as possible.

We were in a once-in-a-generation bull market run of institutional apartment class [as an investment opportunity] from 2012 to 2022. The zero interest rate policy (ZIRP) era was phenomenal for anyone involved in real estate development. Interest rates being low pushed asset values to the moon in every market. Phoenix, Austin, every urban city was going crazy. Even if you didn’t do anything to increase your profitability at the unit, your asset value went up. Generationally good time to be involved in the real estate market.

Since 2022, people have had to look at a lot more things like operations. If you talk to the sophisticated professional investors — the people who are now buying apartments for long-term ownership, rather than to take interest rate bets on valuations — they are focused more on those operational things. I know of several owners who own nearly 100,000 units who will pass on buildings as a result of their mix, saying, “It’s going to be too operationally complex. We know that the income is soft because we can’t operate it well enough.”

The other interesting part of how real estate works is that developers can respond to what prices are today, but the product isn’t delivered for several years. There’s always this lag effect. So what I would hope is that in subsequent years, as people see the market is softening for buildings that are studio-heavy, that developers can change their product to build units that don’t churn quite as much, which is why there is an opportunity for some developers to — on the margin — build slightly family-friendlier apartments.

Recently, you were posting about the floor plans of pre-war apartments. They have slightly smaller common living spaces, substantially fewer bathrooms, and sometimes closet space for the second and third bedrooms is constrained. There is a second and third bedroom. What you’re pushing for in the industry is, “We should do more of what developers have done historically.”

Yes, yes, yes. Most of the best ideas are ones that have been done before and proven to be true. Building for long-term ownership, aligning incentives — looking to the past, not in the nostalgic way: more like, it has worked for a while. It’s one of the reasons the product I’m excited about building is two- and three-story connected row homes. People have lived in those units for millennia. There’s a good reason for it. So yes, pre-war units are better.

We can look to reform our current building codes. One of the things I find most compelling about the Yes In My Back Yard (YIMBY) movement is people who point out the maps and say, “Here are all the buildings that exist. Here’s the percentage that would not be allowed today.” There is certainly some level of improved regulation — there are some safety ones that are better. But generally, we have improved our ability to fire-rate buildings, we’ve improved technologically, but we’re still not able to build housing product that is built in other parts of the world — or even that already exists in the United States. We should go back to that, with appropriate safeguards.

Let me ask you about policy fixes. One thing you hear is, “We need to fix zoning.” I tend to be in that camp. The counterpoint, and you’ve talked about this, is that if you hold everything else constant, upzoning tends to produce studios and one-bedrooms aimed at singles. You’re not directly increasing the stock of apartments for families. What could you do to make it easier to build family housing in city centers?

I’m not an academic obviously, I’m a practitioner, so my motive for helping the study that we did with IFS was very biased: I wanted it to have the effect of changing the product that gets built.

With that caveat aside, I am leery of additional, well-intentioned government intervention. I’ve had plenty of people ask me, “What are the policies that would be putting a weight on the scale against studios, in order to increase family-oriented housing?” I try to take those off the table, because I don’t like that. There could be a thousand other unintended consequences. At minimum, units should be treated the same. There are some policies that are designed against apartments for families. In many jurisdictions (although not in as many cities, more so in the areas around them), parking ratios are assessed per bedroom, and not per unit. When you have that cost adding per bedroom, you will get fewer bedrooms. If you have to build a parking space for every bedroom, then you will make sure that they’ll be designed for the people who will need two parking spaces, which is more likely to be two roommates, and not a young family who share a single car.

What are policies that could make it better? The power that drives studios and one-bedrooms is higher rents. A 400-square-foot studio in any city in America will rent for $1,200. That is very inexpensive, even for Cincinnati, even New York, where that would be outrageous. That’s $3 a square foot. But for a family apartment, $3 a square foot for a 1,500-square-foot would be $4,500. There are not many cities where that would be affordable for a two-income household, let alone a single-income household. The power of that ratio is what has driven studios and one bedrooms. It hasn’t been that developers or planners or anyone is putting their finger on the scale against families. It’s that it is the best use for short-term rents.

There are other factors that, in small projects or individual units, can make it so that it is not as harmful [for investors] to build something designed for a family. It can be quite rational, as an investor, to take contrary bets. If a new neighborhood has 8,000 new one-bedrooms and studios — well, in five years, we should expect some percentage of them will be couples. Five years after that, some percentage of them should be parents. So we should build at least a portion of those [apartments] for those same people when they’re 32.

What should we be copying from places outside the US? People who spend time in this debate always end up with a favorite country or city overseas. “Oh my gosh, we need to do what Vienna does.” What would your set of wants be from overseas?

You might have met Stephen Smith: he’s a friend, one of the people who’s been talking about single-stair. But that’s probably the easiest example of, we have improved fire rating of buildings and materials.

Our readers are going to be divided into people who totally know what you mean by “single-stair,” and a bunch of folks who have no idea what you’re talking about.

The most straightforward difference between Europe and the United States, that would be the easiest to implement — and there has been success at the state and local level — is changing the requirement on the number of stairwells that you need to have in a building. In Europe there are more buildings that are smaller that have a single stairwell, and then fewer units off of that landing. In the United States, two stairwells are almost always required once you get above three stories.

For fire safety reasons?

That is the justification that’s given. Whether that’s actually safer or not — it’s mostly an issue of, “It’s just safe in general.” Buildings that tall, especially new buildings, are all required to have pressure-rated stairs and sprinklers. So it is extremely unusual for there to be a fire in a new apartment building. The only ones that I’m aware of now are mid-construction, before the sprinkler system is in place. The number of injuries that occur in new apartment buildings in the US is extremely low. It’s an issue of safe versus already safe.

Readers may remember, Mayor Eric Adams in New York got into a corruption scandal involving fast-tracking the fire alarm permitting for the Turkish consulate. Separate from the question of corruption, which is bad, there’s a strong argument that that should not be its own process at all. Every other permit happens through the Department of Buildings: it’s all centralized and you have requirements for the building not to be flammable. The fire department still manages to own this one permit. You make it harder to extort other actors if you consolidate all that permitting.

There are a thousand other ones that are very similar. It’s one of the reasons that zoning isn’t all of it. The other example is, when a decent-sized apartment building is being built, you want to have that building leased as quickly as possible, which means you want to start leasing it in advance of the date people can move in. That almost always involves getting permission from your local fire marshal to allow people to walk through the building to see it. You can have a very agreeable fire marshal, who says, “Yes,” or someone who says, “No.” There are ways for all those different little agencies and city employees to help or hinder projects.

If you talk to any local developer, they want to be friends with everyone in the city. The adversarial nature of some legislation which is designed to whip localities into shape is underestimating how many levers there are for relationships to go sour in building housing. It’s why everyone wants to be nice. They call their city councilman and try to expedite the process — to have them lean on the fire department. Which is extremely common. That thing for which Adams got dinged happens hundreds of times in every city across the country.

Because to fast-track stuff, you’re going to often need to call in a favor?

If you have that relationship, then you would say, “Can you have someone call and ask?” There’s a point at which it tips into corruption, but there’s also a point at which someone who is an engaged local politician does check in with the city employees and says, “This thing is important. Can we make sure that it gets done?” Because it is a priority to get housing done appropriately. So, without being too much of an Eric Adams stan, I would vote for him if I was a resident of New York City [this interview was recorded before Adams dropped out of the mayoral race]. There is a way in which it isn’t blatantly corrupt.

Well, I’ll join you here and say, I would vote for Eric Adams, but he will lose the upcoming election. So it doesn’t matter at this point. Some of the other corruption stuff is quite bad, a real black mark, but expediting a fire permit seems like a nothing-burger to me. There’s other stuff that he’s done that’s more egregious.

Anything else I should have asked you about?

I don’t think it’s often appreciated by laymen how much of an impact short-term private equity has had on the type of housing that we build. The vast majority of the capital used to fund apartments comes from closed-end funds. Due to the different types of risks of housing, these funds need to build apartments in order to maximize revenue in two to three years — when the building’s finished.

It’s because there are very different return expectations when you take the risk to go from vacant land to finished building. Generally, an investor wants to have high teens or low twenties returns. That’s because the risk you’re taking is that there is nothing built. So developers buy it, it’s funded with capital out of New York, Los Angeles, or elsewhere. Someone gets a 1.5 times multiple on that money and then sells it to another large institution. Those institutions are going to put long-term debt on it. That’s bought by life insurance companies or people who want steady streams of income.

The effect of short-term capital being used to fund these buildings is that very few people look to the long term. Similar to the effect of private equity rolling up HVAC, or veterinary clinics, or short-term retail buyers in the stock market — when there’s capital that [seeks returns] either quarterly or within two years, it has distorting effects. I would encourage more investors to build and invest in things very long term. Some folks have looked at opportunity zones or other vehicles which encourage investors to put money in for longer periods. More stuff like that is good.

In general, getting more capital into real estate that is built and held — aligning incentives for the city and for investors — is helpful. But as of now, developers are primarily worried about, “How good is New York going to be for my building in two years?” Long-term owners are more, “How is income going to grow?” That is a topic that bears exploring for people who care about cities and believe in capitalism being an important force in that. I think there’s a good critique — for people who are capitalists — who can look at that as investors and say, “How do we do better, knowing this is what the factors are?”

On the financial timelines point, this is something I learned from working with my colleagues. We work on geothermal energy, which is clean, firm, and baseload — there are good things about it if you can get it to scale. To do that, it turns out you have to pay close attention to, “Is this investable? On what timelines could you see returns? What are the blockers? How long does it take to drill a well?”

You could take more risks as an investor in geothermal if it didn’t take five years to get the permit. All of a sudden a bunch of actors, who otherwise cannot invest in this risky technology, could jump in. It’s been part of my adult education to see how, in many industries, financing is the bottleneck. Unless you understand that, you don’t understand the industry.

One of the reasons why comparisons of housing between the United States of Europe don’t work is, we don’t finance them in the same way. They’re largely built by either public or fixed-profit financing vehicles. Whereas in the United States, it’s primarily built with short-term private equity incentives. Charlie Munger says, “Show me the incentive and I’ll show you the outcome.”

Housing, like lots of other things, has become a financialized product. Unlike a lot of other private money types, real estate is a very good way of deploying a whole lot of money. Venture capital is about trying to take $100,000 and turn it into $100 million. Real estate is about trying to take $50 billion and turning it into $60 billion over 10 years. It’s very efficient at that.

Our paper gets into the challenges for the upzoning of middle or smaller projects. Even were those to be permitted, the people with all the money in real estate don’t want to do 10–20 unit projects. They want to do one 200-unit project. It’s significantly easier to deploy one $30 million check, because they’re in the business of deploying $2 billion a year. It’s unsustainable to do that in a linear fashion at smaller check sizes. Those firms have to deploy money and they’re not as interested in maximizing returns by a little bit. Understanding those incentives is key to making the city better. Or else the only product that’s going to get built is 250-unit apartment complexes and 10,000-home greenfield communities, because that’s very efficient for Bain Capital, Blackstone, and Apollo to fund. It’s not efficient for them to fund a great, boutique, 12-unit project with a daycare and coffee shop at the ground floor, which would be phenomenal.

We’ve done the recent past, the present, and what you are working on in the American Housing Corporation. I want to close by asking you to project a little bit into the future. What trends in housing and urban life are you paying attention to? One that you were tweeting about recently is, there’s trouble coming for student housing. The number of 18 year-olds is larger than the number of 17 year-olds, which is larger than the number of 16 year-olds, and we’re in a new place. What other big structural trends are developers looking at when they think about building housing for the next five, ten, or twenty years?

I’m most hopeful that there are enough challenges now that developers are starting to look five or ten years down the road. The bull run of real estate over the last fifteen years has been so short-sighted that almost no developers ask that question, “What is going to happen in the next five to ten years?” You’re just building to get the building up, because you know you can sell it for more.

There are critiques that, “Developers are evil.” A capitalist critique is that there is too much housing being built for the very short term. If you are trying to maximize revenue in two years, it probably does make sense to build studios. You’re not as worried about turnover, or about what’s going to happen to the city down the road. Whether it’s student housing or other things, there’s enough large forces coming into play that I hope both capital and developers are starting to think, “I build this now — what does happen in five to ten years?”

There is enough pressure on both sides that there is going to be densification among new housing types. My company is betting that there will be a wave of state and local laws that will make it marginally easier to build — not necessarily high rises, but slightly more dense housing. That’s positive, and that’s going to continue.

My fear would be — and I say this as someone who’s a conservative who loves cities — I want it to be soon enough. I’m not old enough, and I haven’t seen enough cycles, to be too hyperbolic, because there were certainly much worse times for cities in history. But there has been so much good progress that it feels urgent to not let that generation leave.

What worries me the most is the continued decline of the share of the city population under five. There are a thousand things that need to happen on that one: housing, schools, safety, transit — all huge on their own. They all need to go forward. I focus on housing because one, it’s what I do; but two, it is the appropriate first one — well, safety is probably the bedrock one: you need order for there to be society at all. But after basic levels of order, housing is that first one.

If you can’t pay for the apartment, if the apartment doesn’t exist, the rest of it is a foregone conclusion.

As a capitalist, as someone who’s a Christian and believes in cities, communities, and the power of that force, I believe that the city’s going to get better bottom-up. When there’s a few more people with children around you, it naturally gets better. It gets a lot easier to say, “Let’s all meet at the park at this time.” It is going to have fewer families than some other suburbs, but it makes it so much easier. Schools — one of the solutions is people being friends with other people in the area and all being willing to put your kids in pre-K or kindergarten and then you try to make it work.

There’s other difficulties on the horizon. It worries me that people are trying to copy some of the bad parts of California real estate policy, like eliminating real estate taxes or capping real estate growth, especially for non-homeowners. That one frightens me.

It doesn’t take a lot more families to make keeping your kids in the city feel much more doable. I was in our local park recently. I wondered, “How many kids were there in this neighborhood a hundred years ago?” The average family had five or six kids, so the park would’ve been overrun with kids. I don’t think we’re going back to that. But the bones of New York are totally compatible with a lot more kids living here. There’s no rule that says that cities have to be places for people my age. It’s been our experience, especially post-Covid, that people with families leave. But it is not a fact about New York or any other great American city.

It’s not, and I also think that families being in and around the city is by far the most effective way to encourage pro-natalism. I tend to be skeptical of preaching being effective. If there is going to be preaching, it’s going to be done through people seeing other people in their neighborhood with kids. Little kids are wonderful. My kids are ten, eight, and six. I’ve started sending my wife more pictures of them when they were little. My goodness, I miss little kids — they’re still not big yet, but I miss them. They make the cities better places to be. They force people to focus on real problems, because if kids aren’t getting educated, then suddenly, heads are going to roll.