Today we’re joined by David Schleicher. David is Professor of Property and Urban Law at Yale Law School, and an expert in local government law, land use, finance, and urban development. I found David’s book, In a Bad State: Responding to State and Local Budget Crises, a fascinating and readable primer on municipal debt: what it is, how it grows, and how cities can face up to it.

Municipal pension funding may not sound like the most fascinating topic, but I hope this conversation illustrates two things: First, how our pension systems work matters to all of us — whether or not we are enrolled in a municipal pension. Second, these questions go to the heart of how our cities are run, why they fail, and how they can be improved.

In the sections on Chicago, I’m drawing on coverage from sources including the Chicago Tribune, A City That Works, Illinois Policy, friend-of-Statecraft Judge Glock, the WSJ, and Austin Berg, among others. Thanks to Harry Fletcher-Wood and Katerina Barton for their judicious transcript and audio edits.

For a printable PDF of this interview, click here:

Most Statecraft readers are Gen X or younger. I would hazard a guess that most are not in jobs with pensions, although a large number of readers are civil servants. Most of you readers, like me, have zero personal experience dealing with pensions, and you won’t in the future. This is just my mental model of you, the reader.

So, David, if we’re not future pensioners, why should we care how state and local governments run their pension systems?

To the extent that jurisdictions spend a lot on it, they’re not spending money on other things. When a pension system is indebted, you’re paying for services you received in the past. We’re paying, not only for our school system today, but for our older school system. That means we can invest less in today’s system, because we still have to pay off the money we effectively borrowed when we employed people in the ‘70s and didn’t save for their pensions. It has an effect on budgets; it limits what jurisdictions can otherwise buy.

A pension is just a form of deferred compensation. When you work for any employer, they pay your salary and something for retirement. People who are used to a 401(k) or a 401(k) match understand that the company might help you with retirement. State and local pensions are traditionally not “defined contribution” but defined benefit. If you work for a certain amount of time, you get some kind of annuity — a certain amount of money every year — that begins when you retire. The idea is that the employer will save money while you work, they’ll invest it, and they’ll have enough money when you retire to pay for this annuity every year.

Governments have always offered some kind of pension — there are Civil War pensions. But the modern system of state and local pensions really takes off in the 1950s, ‘60s, and particularly the ‘70s.

A couple of things happen to make it different and notable. The first one is you see public employee unions asking for pensions in negotiations. You start seeing bigger pensions offered.

The second thing is a legal change. Prior to this period, it differed by state, but pensions were called in the law a “mere gratuity.” The government offered them, but then could just not pay them if they wanted to. Then states — through constitutional amendments or judicial decisions — gave pensions the status of either contract or property. What this meant was that they couldn’t not pay them. Pensions had the same legal status as debt, and they were protected by state constitutions and the federal Constitution’s Contract Clause.

Some states went further than this and adopted the California Rule: The pension you’ve already earned is guaranteed by law, and any potential future earnings you have under your current pension policy are also guaranteed, and can’t be changed unless there’s an offsetting benefit. In a California Rule state, which includes New York, Illinois, and a bunch of other states, if you start working as a teacher aged 24, your pension policy can’t be changed until your retirement, unless it’s made better or there’s some offsetting benefit.

Normally, a person borrows money to get an asset, like a house, and governments borrow money to build a bridge. Traditional debt is limited by debt limits. State constitutions have rules governing when debt is issued. Many readers have voted in a debt election, where there’s a bond on the ballot: “Should we borrow $10 million to build a swimming pool?”

By contrast, pension debt — workers worked, but you didn’t save the money for the retirement you are legally required to pay — isn’t covered by these debt limits. In some jurisdictions, it is a particularly attractive place to hide deficits. If you’re legally required to balance your budget and you can’t, underfunding your pension system is a way to bury your fiscal imbalances, by borrowing that is not limited or regulated.

So I’m a governor, and my state legislature slashes taxes, or we promised some big new benefit, and I’m having trouble making the math work. The first place I go to try and make the accounting work is the pensions.

You underfund your pensions. You can do it in all sorts of ways. The biggest way jurisdictions have done this is say in their pension accounting that they’re going to get a big return every year. “We’re going to get 8% returns every year.” They might, but they might not.

New York just did 10.5%.

Sometimes it’s good. But because you’re legally required to pay, an economist would say you should assume the “risk-free rate of return.” If you have an absolute legal obligation to pay something, you can’t take the risk that it’s not going to be there. You’re supposed to account for only those returns that you’d get if you invested in Treasury bills. But that’s not how any jurisdiction works. There are other things you can do to hide how indebted you are, or just get yourself more indebted.

Let’s pretend I’m the governor of New Jersey, which has poorly-funded pensions. It comes to the point where I just can’t pay our debts. I’m supposed to start paying pensions to teachers who’ve just retired. That money does not exist. What happens next?

We haven’t had a state default since the 1930s, because states have extraordinary taxing powers. They can raise the income taxes to very high rates — if they want to. That’ll cause some exit and some problems.

What it means to not be able to pay is an interesting question. Take Detroit. Legally, states can’t file for bankruptcy. Cities can. Detroit did file for bankruptcy under Chapter Nine. But at the moment it filed for bankruptcy, it wasn’t unable to make its next payment — it probably could have, if it sold City Hall. It just would’ve meant that it couldn’t make its future payments. The legal requirement for bankruptcy is insolvency, which is understood to mean not making your payments and not able to make future payments. But what that means is not obvious.

Courts, in the case of Detroit — this is interesting and weird — created an idea called service-delivery insolvency. It was first created for Stockton, California. It was a rule that said, “If your services get too bad, then we’re not going to make you pay on your debts.” What “too bad” meant in this context is not clear. They note in the case — it takes an ambulance an hour to get to you, it’s really bad. But if you are in the Upper Peninsula of Michigan, who knows how long it takes an ambulance to get to. It might take three months.

It’s hard to think of one metric of service delivery that you could apply perfectly across jurisdictions.

There are no positive rights in these state constitutions. Education’s a little different, but there is no right to a level of policing service. But what happens if you can’t pay differs by jurisdiction. States have sovereign immunity: you can’t sue them in their own courts, or federal courts, unless they allow you to. You can’t make them pay. What happens when a state defaults? Mostly, nothing — except that they have trouble borrowing for a long time. With cities, they could be forced to pay, but the state can authorize them to file for bankruptcy.

In the last few interviews I’ve done, I’ve realized that only people in the world you and I inhabit use certain phrases. “Service delivery” is one that I hear used in wonk-world to mean “services the government provides,” but I’ve never heard it in any other context.

It’s true. But also “service-delivery insolvency” — a court just created it out of whole cloth in the mid-2010s. It’s not in the law. The law says “insolvency,” but in order to understand what insolvency means, they insert this wonk-speak, which is not in the statute. It serves a purpose, but it’s just made up. There’s a wonk-to-law channel going through the judicial opinion.

Insolvency is really hard to define here. Let’s say New York has some catastrophic financial crisis. It could sell off huge amounts of property. It could reduce the number of cop cars on the streets by 95%. It’s still doing “policing.” But there’s all these toggles you could turn down before it ran out of things.

This problem emerges in these cases. The courts are struggling with it, and it’s not obvious how to handle them. I don’t think that what they’re doing is best understood as applying a legal test. They’re saying, “When are things so bad that we’re going to allow you to use bankruptcy?”

Let’s talk about your book, In a Bad State: Responding to State and Local Budget Crises. For a book about budget crises, it’s remarkably engaging.

In it, you tell a story of a world a couple years from now, where Illinois and Chicago leadership call a joint press conference and say, “We’re bankrupt. We need the feds to step in and bail us out. The pensions are completely underfunded. Teachers, police, and civil servants won’t get paid unless the feds step in.”

What would happen next?

The book sets out three possible federal responses.

Bailout. We’ve done it a number of times over the course of American history. A jurisdiction is on the edge of bankruptcy, and the federal government — or, with respect to a city, a state government — offers it a bunch of money. Probably the most famous fiscal crisis in American history is the first major one. The states were on the edge of bankruptcy, and Alexander Hamilton and the federal government assumed the state debts.

Creditor loss. The federal government could provide a legal mechanism or otherwise force the creditors to eat the loss. This is bankruptcy, but there are other tools that do this as well, that make it hard for people to recover against governments that they’ve lent to.1

Austerity. Enforce those contracts very aggressively and also not offer bailouts. The loser then would be the people. The jurisdiction would have to raise taxes, cut spending, and sell everything. Maybe that won’t be enough, in the case of a small local government. But Illinois has extraordinary taxing authority. This would be very costly. It would be a huge spending cut during an economic decline. In a decline, people have greater need for social welfare services. You’d be cutting those.

Over the course of American history, governments have toggled between bailout, austerity, and credit loss.

What’s the problem with bailouts? Why can’t we say “We’re going to bail you guys out,” every time?

It’s the problem of moral hazard. If we offer bailouts, everyone will get themselves into trouble, so that they get bailouts. This can operate through two channels. The traditional idea is that governors will look around and say, “They’re getting a bailout. We should also be spendthrifts and get a bailout.” The degree to which that happens is debated, because you’re making predictions across time. Does anyone say, “40 years ago New York City got a bailout. Therefore, I will get it”?

The other mechanism for that moral hazard is bond markets. Lenders can say, “When push comes to shove, they always get a bailout.” There’s a good bit of evidence that that channel works. One example is, a bunch of states got into fiscal trouble in the late 1830s. Nicholas Biddle — who, for American history buffs, was the head of the Second Bank — after the end of that bank, he’s still the head of the US Bank of Pennsylvania. He goes to London and says, “You don’t have to worry about your Pennsylvania bonds. The federal government always bails out states.” Then they didn’t.

It’s famously hard to short municipal bonds. Why can’t I say, “Chicago or Illinois are not going to pay these back,” and make money on that?

There are credit default swaps on some municipal bonds. They’re generally pretty thinly traded. There are technical reasons why an actual short, to do with the reason people like to hold them: interest on municipal bonds is tax-exempt. Changing hands would change who would gain income from them, so it means that shorting is quite difficult. That’s the broad story, but it’s just not a thing. There’s no mechanism.

If you were able to short municipal bonds…

The default rate in municipal bonds is extraordinarily low. There have been many historical instances where that’s not true. In the Great Depression, there was a huge number of defaults of municipal bonds. In the 1860s and 1870s, after the Civil War, municipal bonds were defaulting left and right. The default rate is quite low on municipal bonds: it’s in the 1% rate. The big spike involved Puerto Rican municipal bonds. So another reason these markets don’t develop is because it seems pretty unlikely.

What about Chicago and Illinois makes them the canonical example of state and municipal budget trouble?

This is a famous case — I don’t mean it’s Taylor Swift famous.

It’s the Taylor-and-Travis news of the pensions world.

Chicago has four separate pension funds. All are in dire shape:

The Chicago Municipal — the regular civil servant pension system — is one of the worst-funded in the country.

The Chicago public schools operate one of the most underfunded teacher pension plans.

Illinois has the worst-funded state pension system in the country.

No major US city has a worse credit rating than Chicago. It’s got more pension debt than 43 US states.

7 of the 10 worst-funded local pension systems in the nation are in Illinois.

How does something like that happen?

In the 1970s, the big question was why was Chicago so fiscally well run. There’s a wonderful book by political scientist Ester Fuchs called Mayors and Money. Why did New York go bankrupt when Chicago didn’t? The answer she gives is that in New York, the political machine died, and the result was no centralizing function: they gave money to everybody. Whereas in Chicago, people were either for or against the Daley machine. That machine had an incentive not to get into a lot of fiscal trouble, because if it did, it would be punished politically.

One of the ironies is that Chicago’s fiscal troubles get a lot worse when Daley’s son is the mayor. He’s a much weaker political figure, and ends up spending more than they have across multiple dimensions. Pension debt is the biggest, but Daley also sold off parking meter revenues to balance the budget. Selling off future revenues is not debt, but it’s like debt.

All it takes to have a pension crisis is to have budget deficits forever. In Chicago’s case, they also offer rich pensions. But to have a pension debt, you don’t need to have particularly expensive pensions; You just need to not save money for them. Some jurisdictions have very expensive pensions. New York State has a pretty well-funded pension system: they have very high taxes and they pay for them.

Chicago has just not saved enough. Unlike the federal government, they can’t print money to solve their problems, and they don’t have the taxing power: people can leave Chicago — many people do.

Right now, Chicago is paying its teachers, police, and civil servants their pensions. It actually just juiced the amount it’s paying out, and the state General Assembly unanimously said, “Go ahead.” What is the problem for Chicago now?

They pay out the teachers every year. But the increasing amounts they have to, or should, pay on their pension squeezes what they can pay on everything else. That amount of money they can pay for other things shrinks every year. Eventually the piper has to get paid.

40% of the money the city of Chicago spends every year is debt and pensions. No other big city in America burns as big a chunk of its budget that way.

That’s what it actually pays. Never mind what it should pay. To amortize the debt over time, it should be paying a lot more. You are really talking about all of the money.

In theory, the state could authorize them to raise taxes. Chicago already has quite high property and sales taxes. Chicago voters turned down — I thought it was pretty poorly conceived — a property transfer tax recently, that was designed to pay for an additional set of programs. There are just limits to how much people will pay in tax. At some level, you start to see exit and economic pain.

You have seen that in Chicago, especially compared to other big cities that have contemplated raising taxes. Flight from New York is more of a media thing than a reality, when you look at the data. California, there is some exit. But Chicago has had outflows of very rich people to all kinds of other places.

The studies on flight are really interesting. They are usually about top-end personal tax increases. The evidence is that there’s a very little bit of flight in response. Part of the challenge is that all these studies are pre-COVID and pre-Zoom. Whether that changes things is a little unclear.

The social meaning is a little more complicated. One thing is the tax rate going up 2%. Another thing is the message, “You’re not wanted.” I don’t know what’s going to happen with exit. But one of the challenges for these jurisdictions is a lack of entry.

Meaning no mega-rich people are moving to Chicago?

I’m thinking about New York. Their share of the richest 1% has declined over time. A little bit of that is exit, but some of it is the absence of entrance.

As we see greater income inequality, one person can be a big deal. There’s a famous story involving a very rich person named David Tepper. He owns Charlotte Football Club and the Carolina Panthers. He left New Jersey and the lost tax revenue was a big deal. Ironically, he moved back during COVID.

In addition to the exit questions, it’s just economically punishing to have higher taxes and worse services. If you actually try to pay back your pensions — as opposed to getting a bailout or stiffing the investors — the result is a depressing politics for a long time, where you’re spending less and taxing more.

Connecticut is remarkable. It was one of the most underfunded pension systems, but since the late 2010s it has been extraordinarily responsible. It’s a much more complicated story about budget controls and bond covenants, but they’ve saved a lot of money every semester. The result of this is they’re neither cutting taxes — they cut taxes a little bit last session, but not this session — and they’re not raising spending. It’s just a downer.

Another way of saying this is you start thinking about generations. Why is politics so depressing in Connecticut? The boomers spent all the money and we’re paying off their debts. But Chicago might be much worse than that. It’s more than just something that can be solved by making your politics a little bit of a downer for a couple of years.

What other big cities or states are in the comparable range?

Pensions are in much better shape now than they were 10 years ago. We’ve been discussing the pension crisis for a long time, and the last number of years have been quite good for state budgets.

How much of that is that COVID?

A good bit of it. The states got a huge amount of money from the federal government. They were not supposed to spend any of it saving for pensions, but they made their pension payments. Even the most spendthrift ones — New Jersey would issue press releases, “We made our pension payment this year.” Which is like issuing a press release, “I paid my credit card.” You’re supposed to! State budgets were in bad shape before, but they’re not getting worse in most places. The desire to hide budget deficits has gone down.

In terms of jurisdictions, Illinois and Chicago are much, much worse than all the others. There are other measurements you could use that have Connecticut and New Jersey in bad shape, but those are the richest places in the history of Christendom. Their ability to bear the debt is better.

The real problem of Chicago is that the city has these unbelievably indebted pension systems — 18% funded. But then they’ve got the school districts. The complex relationship between those two entities — who’s borrowing to help who — is the subject of a huge fight right now. But the overlaying — the city, the school district, the parks district, the county, the transit district, the state — leads to nesting dolls of debts.

From the perspective of a taxpayer, you have to pay out all of it. This is something people don’t often realize about jurisdictions, but when most people pay their property taxes, they are paying to multiple jurisdictions. In Illinois, people will pay taxes to 13 separate jurisdictions that are overlapping in complex ways.

I’m still curious about how something like this happens. There was a bill that passed the Illinois General Assembly — Governor Pritzker just signed it — that boosts benefits for the city’s first responders to the same level as other people in the pension system. The cost is about $11 billion in pension liabilities. It deepens next year’s projected deficit by more than $1 billion dollars. It’ll probably receive another credit-rating downgrade for the City, and it passed the Illinois State Assembly unanimously.

How does something like that pass unanimously, when every accountant looks at it says, “This is horrifying”?

Chicago has what are called tiers of pensions. This is driven by the fact that they can’t change pensions policy for current workers at all. There’s a great Illinois Supreme Court case where they tried to do this, and the court said, “You can’t change things for current workers.” What they do is create a new tier when they want to cut pension spending going forward. They create these second tiers for workers. Those workers — who are doing the same jobs as previously-hired workers — will be earning pensions according to a different policy. What this did was change the policy for one of those tiers of workers to make it more like the other tiers of workers. It made it sweeter. But remember this is happening for police officers and firefighters. One side of this argument is scolds…

People like me and you.

Exactly. “This is going to be a problem in the future! My bow tie is out of whack!” The other side of this argument is the extremely powerful moral claims of police officers and firefighters who’ve been putting their bodies at risk for you, the citizenry. The problem is accruing over time, but probably won’t come to a head this year, or next year, or maybe not for fifteen years. Current officials face incentives where it’s, “Should I help out the firefighter today? Or should I think about the fiscal health of the city twenty years from now?”

When you put it that way, it’s pretty obvious.

This dynamic is exactly the central problem. The Illinois legislature — when they were creating their California Rule-like constitutional protection for pensions — had a debate about whether this exact dynamic would happen: whether jurisdictions would have incentive to under-save. What they said was, “We’re not going to put in a mandatory savings rule. We’re going to make it legally protected. The legislature will never take risks if they have a legal requirement to pay in the future.” They were wrong.

I get that it’s hard to go against the firefighters, the police, and their unions, and it looks really bad. Especially at a municipal level: if you’re in Chicago itself, they’re breathing down your necks.

But if you’re a state assemblyman from way out in rural Illinois, why isn’t there more incentive for you to be the brave truth-teller saying, “Chicago has been putting off its responsibilities for too long and I’m not going to put up with it any more”? Why is the vote unanimous?

Part of it is that you regularly see, with respect to local legislation, what are called universal logrolls. If you are from Springfield, you don’t want to get in the way of what Chicago wants — if you do that, the Chicago representatives will get in the way of what you want for Springfield, when you require state approval. That dynamic also helps explain the budget problems at the city level. Officials who want money for a new park know that this is going to crowd out their ability to borrow or spend in the future. But the go-along-to-get-along politics, particularly in the absence of sharp partisan competition, can result in these universal logrolls.

This is a point Barry Weingast famously made in the political science literature: it’s just the logic of the pork barrel, but applied to lots of different things. That dynamic is pretty powerful in the state legislature, and that’s what you saw. There’s an interesting question of why the governor didn’t veto the bill. If anyone’s in a position to be the voice of reason here, it’s the governor.

He’s got national political aspirations too.

He’ll have to defend it. But that goes both ways, because he’d have had to defend vetoing it, if he’d done that, to the teachers and firefighters.

Let me go back to your book, In a Bad State, about what the federal government should do if it’s asked to bail out Chicago. No matter what you do, somebody is holding the bag at the end. What principles should our president in 2030 use to think about this?

All the choices are bad. There’s austerity, usually in a recession; default, which limits your and maybe other jurisdictions’ ability to borrow in the future; and bailout, which creates moral hazard. What should you pick?

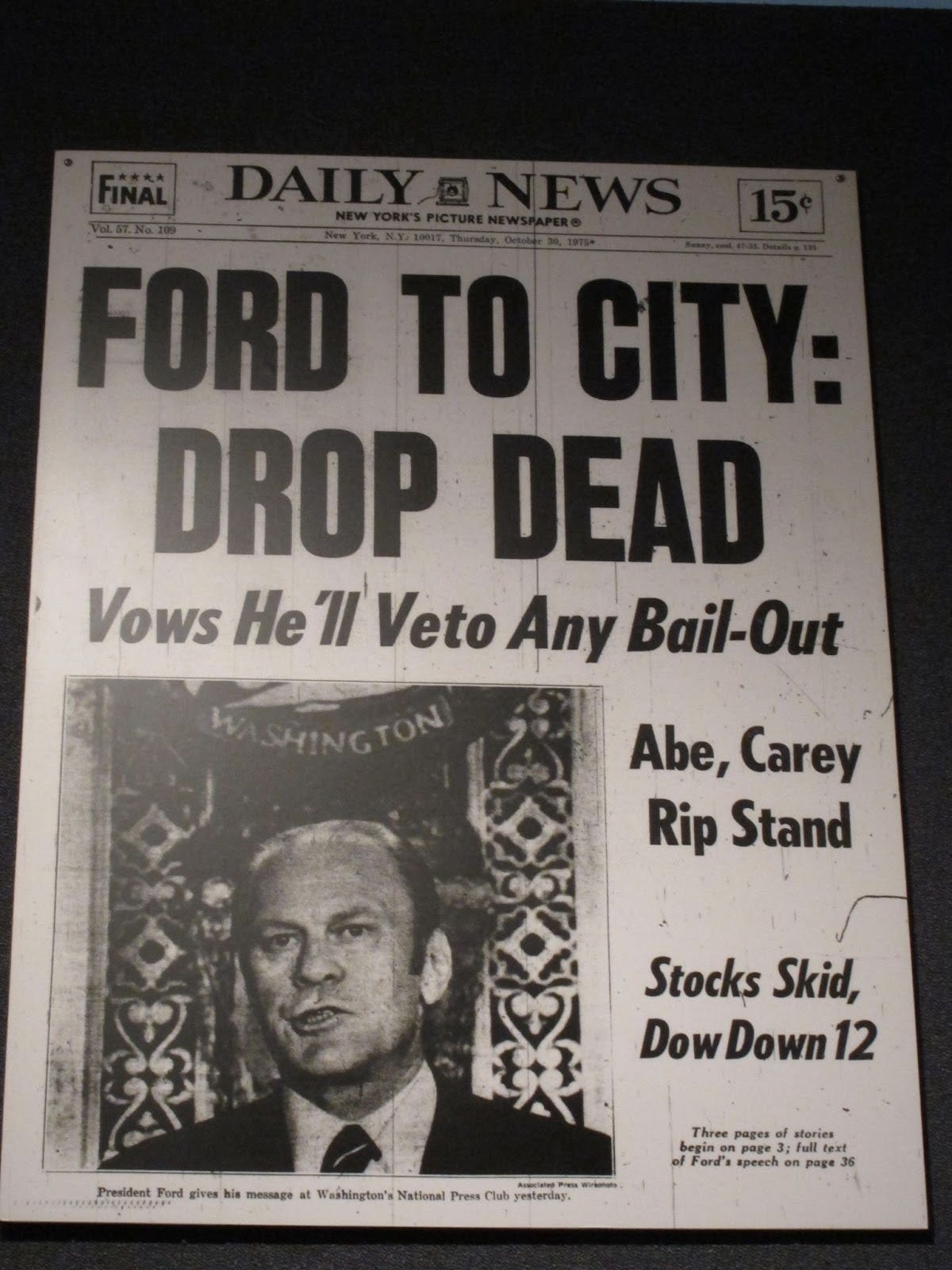

The US has picked all three at different times. You can go through different fiscal crises. The best responses are not all one or all the other. They mix elements of bailout, austerity, and default. For instance, in the New York City fiscal crisis, famously, there’s a headline, “Ford to City: Drop Dead,” where President Ford is saying, “I won’t bail out New York.”

But after the city quasi-defaults, engages in austerity, and creates a new governance structure, the federal government offers emergency loans through the Seasonal Financing Act. There’s a marginal increasing cost to all three [responses]:

A big default will stop you from borrowing for a very long time. But a small default: “We might get over it, especially if it’s a technical default.”

Austerity: if you have to cut everything, that’s bad. To cut some things — that’s less bad. It gets increasingly bad over time.

A big moral hazard is much worse than a small degree of bailout: jurisdictions are getting money from the federal government all the time.

Engaging in a little of all three is much more attractive than choosing one or the other.

What would this look like? For instance, bankruptcy. Jurisdictions regularly engage in a good bit of austerity, because of the insolvency requirement. Once they do, the court will say, “Now you’re insolvent. Therefore you can start impairing creditors.” After the bankruptcy started, Detroit found a combination of foundations and the state government offered money to help the city pay off some of its pensions. So it got a bailout, but after it already suffered.

That reduced the amount of moral hazard. If you are a politician, you’ve already taken the hit for going bankrupt. You’re living in infamy forever. Getting the bailout later reduces the harm without putting in much moral hazard. That would be one good metric: “What can we do to do a little bit from all three of these, rather than doing all of one, or all of them?”

The other thing you should be thinking about is taking advantage of these crises to set up rules that work well in the future. In the wake of the New York City fiscal crisis, a requirement was imposed on it to use honest accounting rules that limit your ability to get excessively indebted going forward.

Were they using dishonest accounting rules beforehand?

100%, yes. Government jurisdictions account on what’s called the cash basis. Do you have as much money coming in as going out? But that doesn’t affect whether you accrue debt over time. New York City was borrowing money to balance its budget every year. Jurisdictions do all sorts of weird stuff.

What are the most malicious ways to hide problems with the budget?

The funniest are what are called lease-and-buyback agreements. To balance its budget one year, Arizona sold the State House, then made an agreement to buy it back in the future, with payments every year. This looks just like a loan. You make annual payments and a lump-sum payment at the end — but it didn’t count as debt. The craziest ones are when they do lease-and-buyback for jails.

Another trick is not paying your suppliers for a long time. Governments use a lot of paper. You can pay a premium for paper, but agree, or tacitly say, “We’re not going to pay you for six months.” That turns the paper company into a lender. They’ve cleaned this up a bit, but Illinois had a very long lag time in paying off ordinary suppliers. That increases the cost, because it’s a loan. The idea that everyone who provides staples is effectively a bondholder of the State of Illinois is a pretty amusing one.

One move you mentioned in In a Bad State — it felt obvious the moment I read it, and I’d never thought of it before — was creating a new legal entity, shifting all of your debts onto it, and then saying, “Sorry, you can’t sue us, we’re a city with no debts.”

A number of jurisdictions did that; Port of Mobile is the one that made it to the Supreme Court. The City of Mobile owed money, so they created a new city called the Port of Mobile. The state legislature is allowed to create new cities. The Port of Mobile contained most of the city of Mobile. Now the power to tax property is given to the Port of Mobile and not the City of Mobile. By the way, the Port of Mobile is going to buy Mobile’s assets for a dollar. The Supreme Court just said, “You can’t do that. We don’t really know why, but you definitely can’t.”

It’s not really obvious why that’s constitutionally illegitimate, but you can’t do that.

Now we explain that as a violation of the Contract Clause: states can’t impair contracts, this is understood as a functional impairment of contract.

These massive public pensions are relatively modern. Why are public pensions structured so differently from private ones? If I’m a private company and I want to offer a pension to my employees, I have to use real actuarial projections, fund the pension every year, and buy pension insurance. I can’t pull accounting tricks.

If I’m a state or local government, I don’t have to do any of those things. Why not?

It used to be that defined benefit pensions were much more common, and they were getting into trouble. Congress passed the Employee Retirement Income Security Act (ERISA) that imposed all sorts of obligations upon holders. Most of your readers don’t have these things because companies have moved away from them, towards defined contribution systems, and 401(k)s particularly.

Congress didn’t apply ERISA to state and local bonds for two reasons. One is that state and local governments don’t default that much. Secondly, these restrictions would be thought to be a pretty big imposition on the rights of states. States and cities were very resistant to any limitations on their ability to do their own internal budgeting. That’s how they diverged.

The big story is that the defined benefit pension has fallen out of most of the private sector, but remains in the state and local sector. A few states have experimented with moving to defined contribution systems, but it’s a rarity.

One thing we haven’t talked about so far is how you should manage pensions. Some are passively managed. Famously — or “famously” — Nevada has fully passively-managed pensions. The guy who manages the pension puts the money in indexes, and he sits in his office all day and plays Doodle Jump on his phone. There’s an interesting report that if Chicago’s pensions had been passively managed in 2024, instead of spread across more than 80 management firms, the city would’ve saved $40 million in management fees and returns would’ve been about 25% better.

Should everybody passively manage their pension?

It’s something that the literature is a little unclear about. It depends a lot on the jurisdiction and how well-managed its pension fund is. There are potential gains from active management. The question is, should you expect your jurisdiction to achieve them? There are jurisdictions that are just very well run. Utah — they just run everything very well in Utah. I don’t know how they do it. Everything works out. If I were talking to Utah, I’d say, “You guys are pretty good. You do what you want, you can take some risks.” Other jurisdictions, I don’t know.

One thought is that because you’re creating a long-run obligation, like a university endowment, it provides capacity to invest in things that don’t have short-term returns. They should be able to invest in weirder things that give them greater returns, because they’re managing in the long run. Pension funds are the classic source of funding for alternative investments: private equity and hedge funds.

The challenge emerges: you have the world’s sharpest financial figures on one side of these negotiations; on the other, you have well-meaning civil servants who are a little bit outmanned. They’re holding giant sums of money. This has led to all sorts of abuses, like the disputes around Alan Hevesi, former New York City Comptroller, and Steven Rattner, a big-time investment banker who manages Michael Bloomberg‘s and the New York Times‘s money. [Pension funds are] also the biggest players in securities fraud litigation: a huge percentage is brought by CalPERS, the California pension funds. There’s a question: can they do this?

Some jurisdictions around the world have turned their pension funds into extremely well-paid financial firms. The Ontario funds: the managers make millions of dollars and it’s a pretty fancy operation. There’s potential gains to be had from this. The question is, can you pull it off?

Even if you’re [earning good returns], you shouldn’t account for that. Jurisdictions traditionally use their expected earnings to target what they should save going forward. They say, “We made 8% this year. We should save as if we are going to earn the same amount in the future.” But that doesn’t track, because you have to pay regardless of whether the financial year is a good year.

There’s a complicated thing about what the money should go into relative to the jurisdictions. You would prefer it to be things that are up when your budget is down. But there’s political pressure to do the opposite. Some jurisdictions invest their pension funds in affordable housing in their own jurisdiction.

Which is tightly correlated with the success of the jurisdiction.

On the other hand, there’s a lot of political pressure to do that. It can be a real challenge.

Do we have any evidence that the places that pay their pension managers a lot more do better at active management? I would imagine, if you’re getting paid millions to manage the Ontario pension plan, odds are you’re doing a better job.

There just aren’t a lot of instances of these [funds]. And it’s not like we’ve randomly dropped them on jurisdictions. One reason you’d move to having a privately-run organization, that’s outside of your control, is because your jurisdiction is incapable of doing so otherwise. Just like if someone is a problem person, you might want to put all their money in trust. So it’s a little hard to say.

Because you are a Renaissance man with a wide variety of interests, I’m going to ask a few rapid-fire questions. Let’s start with your pitch for building more big infrastructure at the federal level: The Priority List. Sell it.

It’s widely understood that American infrastructure has a cost problem. It costs more to build subways in America than it does anywhere else in the world, by huge margins. The cost of building highways is both more than in other jurisdictions and increasing over time. [Zach Liscow recently discussed why this is on Statecraft.]

Similarly, there’s research into what might fix this. One big bucket of potential problems is about management of projects: states and cities plan badly, plan weirdly, and are overmatched by their contractors. The second is regulations driving up costs. You guys are state capacity people, the National Environmental Policy Act (NEPA) stuff, CEQA — you get the idea [Statecraft has covered the challenges NEPA poses].

Everyone knows these reforms are politically difficult to achieve. The priority list is an idea of how we might enact them. The idea is that Congress should, when it’s approving its general transportation bill, give the Secretary of Transportation the ability to designate 10 or 20 super-duper important, super-popular projects. This would involve sending a crack team of federal experts to help jurisdictions plan, giving them special financing tools, and exempting them from a whole variety of regulations — for just these projects.

The idea is that Congress might not be able to pass NEPA reform, but for the projects that are most important, they could attach these exemptions, and use the projects’ popularity to achieve the political reform they can’t achieve more broadly. Then those projects would be an example.

What kinds of projects would fall into that super-popular bucket? I’m having trouble picturing what would be overwhelmingly popular.

Think of whatever China’s doing, and then imagine it on an American scale: a giant new subway system, a new big highway, a big transmission system, big pipelines. [Statecraft has discussed what China is doing with Dan Wang.] You can imagine any number of things that fit within these categories. You’d have to spread them out, because it’s Congress. But it’s not that hard to imagine. If you think on the scale of the Golden Gate Bridge and the bridge that connects Detroit and Canada — big deal projects. Anything that the president would find it useful to go and do a ribbon-cutting for. For the current president, we could coat it in gold.

When you say, “transmission systems,” or “subway systems,” these have widely-shared benefits. You could bring down energy prices with better transmission and reduce travel times all over a city with a subway system. But famously, the costs are concentrated and any of these big projects would have a strong lobby of people who hate it.

Why would this get around the problem that people always hate projects with more ferocity than the people who want to build them?

These would be national goals and they’d be the kind of thing that the president and leaders in Congress could brag about at election time. “I was able to achieve the new Big Dig. While everyone else talks about doing infrastructure, I did it, and here are my 10 examples.” That mass politics could defeat NIMBYish politics.

Another easy question. Does zoning matter more or less in an era of remote work?

It matters both more and less. Across cities, we’ve seen an increase in the value of office, rent, and housing space in suburbs and exurbs [compared] to downtowns. We may have seen some movement across jurisdictions. That has the effect of making suburban land a little more valuable, relative to urban land.

It may reduce housing costs where it’s reducing demand, but it will increase demand in other areas. It might make commutes better, so there’s more developable land, which might reduce housing costs. But those areas are themselves tightly zoned. [Statecraft has discussed zoning problems, and the Senate Housing Bill addressing them.] The ability for the market to allow housing to be built in the exurbs of New York City, relies on agricultural space being turned into housing.

One of the big areas that has seen huge run-ups in value in the post-pandemic era was in Connecticut, in Fairfield County. But you see one or two-acre lots by law. These are the richest places ever: Greenwich and Westport, Connecticut. There’s been even greater increases in the value of these things, as people are commuting a little less. But you can’t build housing there. There’s still a housing crisis in New York City, even if it has taken a little bit of the edge off it. It’s not like it’s become not a problem in those places.

Also zoning can be a problem even in places that are losing population in the Midwest. It can limit the ability to transition land uses.

If I’m a city in rural Illinois and I’m losing 500 people a year from a city of 50,000, why should I care about zoning?

Zoning controls not just the building of new apartments — which is the example that people leap to — it involves the uses of land. What you might want in a jurisdiction like that, is to knock down houses and put up a tree farm. Anything that’s changing, if the law doesn’t change to match current demand, that can create a problem. You see real problems in declining jurisdictions related to the ability to open home-based businesses in areas that had previously been all residential. These jurisdictions need jobs very badly. The land-use problem is about transition. We have a law that fits current uses, and then the world changes. If the law doesn’t accommodate that, then we can run into dislocations.

We haven’t talked much about the New York City Charter Revision Commission, which — relative to pensions — is even less famous. You could change all kinds of ways New York is governed and some people would still not want more housing. Explain to me why you’re optimistic. [This interview was recorded before the revisions were approved by New Yorkers.]

There’s a famous quote from H.L. Mencken: “Democracy is the theory that the common people know what they want, and deserve to get it good and hard.” The modern political-science response to this is, “Democracy can be structured in many different ways, and those things will have different outcomes.” New York City won’t become Houston, no matter how you aggregate votes.

The Charter Revision Commission is about changing the methods of aggregation. One simple thing it does — it’s going to require the state legislature to agree — is move election day to an even-numbered year. Why is this important? It would mean more people vote. There’s a lot of evidence that when you hold elections in odd-numbered years, fewer people vote. This has systematic effects on who votes. When you have elections in odd-numbered years, you have much more turnout among homeowners and much less among renters. It’s much whiter and richer. Both [odd and even year elections] are democratic. It’s just that this system would encourage different people to vote, which will have different systematic outcomes on housing.

There are other reforms to the process of decision-making. Zoning changes that include a degree of affordable housing need to go through a process that includes getting voted, “Yes,” by the city council, and the mayor. There are steps before that, but those are the two final steps. In the context of a legislature that doesn’t have partisan competition, we generally see something called councilmanic privilege (or or member deference). The idea is that when a zoning change is made in a neighborhood, that councilperson gets to decide, with no one else having any input. It’s the exact same dynamic we talked about earlier about universal log-rolls.

What the charter revision does is change it. Even if the City Council votes, “No,” after it’s gotten, “Yes,” through all the other processes, that decision can be vetoed by a combination of the mayor and the borough president. It creates a check on this, “Neighborhood gets to veto what happens in its neighborhood.” The borough president is the county-level official. The mayor’s a five-county-level official. Again, both rules are democratic. They’re just different rules that say, “Broader elected officials can veto this neighborhood-level competition that’s driven by dynamics in the city council.” This should make rezonings easier, because mayors and borough presidents are generally more pro-growth than individual members. [For more on how New York City works, Statecraft recently spoke with Maria Torres-Springer, who is running Zohran Mamdani’s transition team.]

This might be the most interesting conversation I’ve had on pensions and local-government bailouts in a long time.

There are really dramatic stories here. If you want to know why the South didn’t develop infrastructure in the second half of the 19th century — it wasn’t able to borrow. If you want to know about history of corporate suicides like Port of Mobile, or what happened in New York in the 1970s — municipal debt seems boring, but it’s the history of America.

The losers would just be the poor saps who thought it was a good idea to buy what?

To buy Illinois bonds, or to work for the State of Illinois — anyone who’s a creditor. There are a lot of ways to make them the losers.