Three things today:

The Recoding America Fund just launched

Reflections on the 2025 Progress Conference

Interview with OSTP Director Michael Kratsios

For a printable transcript of this piece, click here:

1. The Recoding America Fund just launched

First order of business: Jennifer Pahlka has been working on this project for a long, long time, and I’m privileged to be a part of it. Here’s the announcement:

TLDR: The Recoding America Fund (RAF) is a new philanthropic effort to deploy $120 million over 6 years into building state capacity. Specifically, the fund aims to help government:

Attract and retain the right people

Task them with the right work

Via purpose-fit systems

And test-and-learn frameworks

Some of this may sound familiar, and of course it is: Jen’s been on Statecraft more than any other guest, and her book Recoding America has been hugely influential for my generation of policy thinkers. In particular, Jen helped me get my head around an idea I’ve been writing about over the past three years: if you want federal bureaucrats to act less like federal bureaucrats, get rid of the rules that require them to act like federal bureaucrats. Most of our frustrations with government inefficiency and ineffectiveness come from rules that constrain people working in those systems. Reform efforts that just focus on headcount or on further constraining the government may be good or bad ideas on their own merits, but they won’t make the government more efficient, because bloated headcount is not why the government is inefficient in the first place.

I’ll be serving on the RAF board. Jen’s assembled a really special team from both sides of the aisle. Especially exciting to readers of this newsletter will be Anne Healy, the new CEO, who served as Dean Karlan’s #2 when he was chief economist of USAID. We talked to Dean on Statecraft, and you can get a sense of the lens his team brought to policy impact here:

2. Reflections on the Progress Conference

This is my second time attending the Progress Conference (and its second year running). Suffice to say, I have strong preferences about how conferences should be structured and run, and each year I’ve attended this conference, I’ve been wowed (and both times I’ve learned new tricks for hosting vibrant intellectual events). Brilliant people, excellent venue, the right balance of structure and serendipity, high production value. Get your tickets early for next year.

A couple of friends wrote up their thoughts on the conference, including Quade MacDonald, Corin Wagen, Shreeda Segan, and Simon Grimm, and I’m sure there will be more write-ups elsewhere. Some discrete takeaways for me:

Last year, I thought global fertility was a strangely overlooked topic at the conference. This year, there were several scheduled conversations on the topic, and far more interest.

On the flip side, this year’s edition was missing a battle royale between Tyler Cowen and the Lighthaven rationalists on whether AI doom can be modeled economically.

Jan Sramek of California Forever presented a very compelling case that the new city they are building northeast of San Francisco has legs: both that they will be able to build it, and that it can be viable in the long term as a midsize urban agglomeration.

Marc Dunkelman presented a very interesting case study on why *picking* bad infrastructure projects may be as big a problem as spending too much on the projects we do pick. I’m not sure if it fully convinced me, but it was a new lens on an old problem.

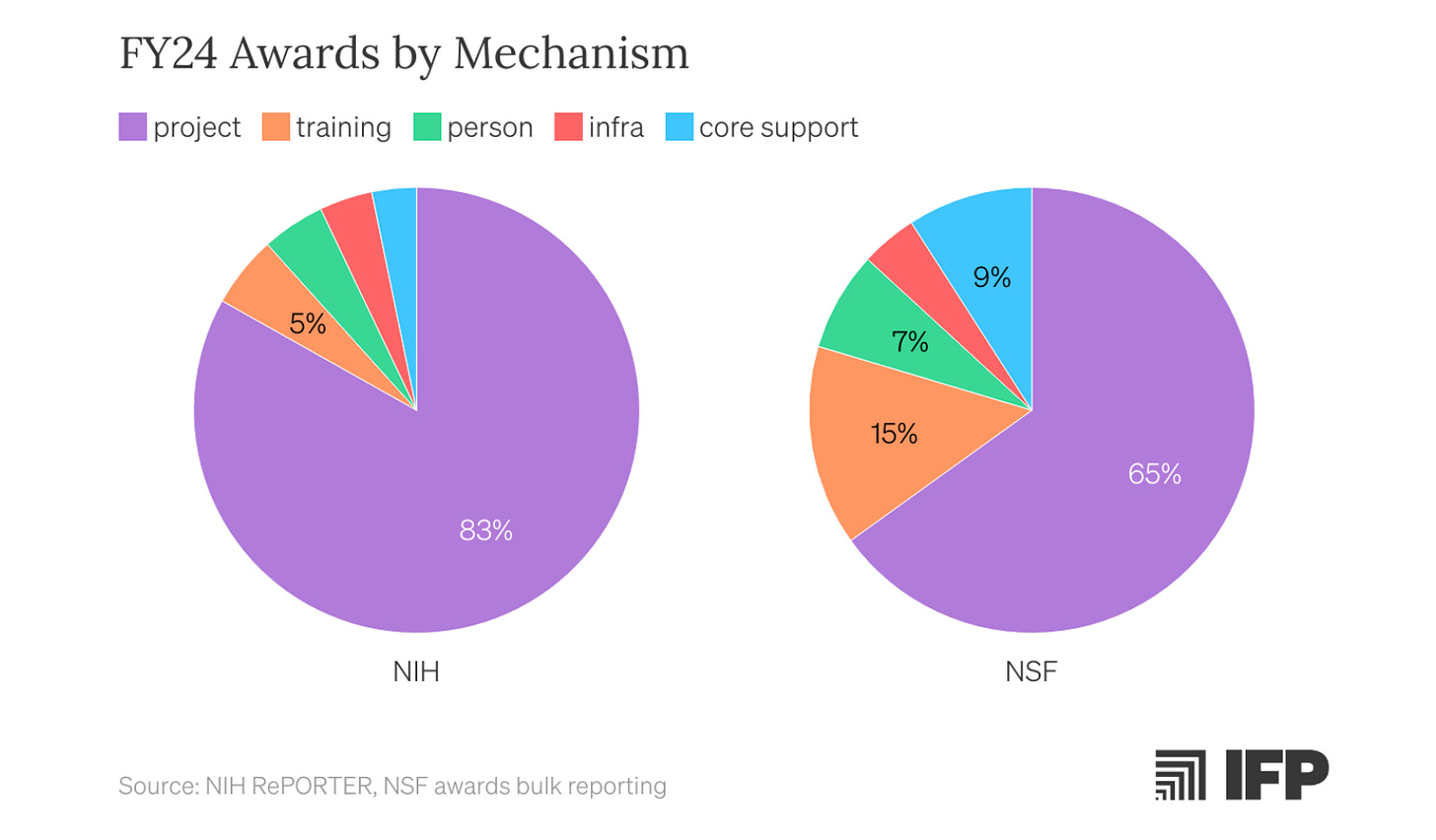

IFP co-founder Caleb Watney analyzed the American scientific portfolio, sliced along several axes. One stark conclusion: we may be overweighting project-based grants, relative to all the other ways one can fund science.

There was more conversation about industrial production than expected. Dan Wang and Brian Potter have successfully convinced this corner of the intellectual world that physically generating things is important.

Speaking of physically generated things, Works in Progress previewed their print edition, and it looks both beautiful and readable (sometimes, fancy new print editions of things only go 1 for 2).

Following a productive dialogue, I resolve to dunk less on Europe and its anemic economic growth. Specifically, Simon Grimm convinced me that while the EU itself is as bad as Americans perceive, there are all kinds of useful state capacity lessons from individual European countries. I must paint with a finer brush.

13 years ago, Ben Thomas and I spent a summer together scrubbing toilets and operating industrial dishwashers at a summer camp in Ligonier, Pennsylvania. Although the conference was made possible by many hands, Ben was the most hands-on organizer. Operational excellence is operational excellence.

I asked OSTP Director Michael Kratsios if the US government has secret stargate technology, and he did not say no.

On that last point:

3. An interview with OSTP Director Michael Kratsios

This episode was originally recorded on October 18th at the Progress Conference in Berkeley. Because of the federal shutdown, Director Kratsios called in virtually.

Kratsios is Director of the White House Office of Science and Technology Policy, and the president’s top science and technology advisor. In the first Trump administration, Kratsios was US Chief Technology Officer, and later acting Under Secretary of Defense for Research and Engineering, where he championed emerging tech like AI, quantum, and autonomous systems in defense.

Given constraints in the topics Kratsios could speak on, my questions focused on understanding the administration’s AI and science policy. We talked about the recent AI Action Plan: what AI can do for America and the world, and how the administration plans to ensure US leadership. We discuss the administration’s vision for gold standard science, and whether the structures we use to fund science need to change. We also touched on how the second Trump administration differs from the first, and Kratsios’s take on AI safety.

Thanks to Harry Fletcher-Wood and Katerina Barton for their light edits for length and clarity in the transcript and audio, respectively, and for a tight turnaround. The White House has not yet cleared the full video for publication, but we’ll share it here if it is cleared.

You gave a speech in April about the new “Golden Age of American innovation.” You said it’s “On our horizon, if we choose it.” It was a compelling speech about how stagnation is a choice. You also said, “Our technologies permit us to manipulate time and space.” I saw quite a few conspiracy theorists jump on the turn of phrase. Does the US government have secret wormhole technology that you’re hiding from us?

I will tell you that was one of the most exciting speeches that I think we gave this term. It really set the foundation for where we want to go as a country on technology policy more broadly. The main thrust of the speech was around technological stagnation. To me, it’s an absolute tragedy, the extent to which progress in the world of atoms has slowed down over the last few decades. Part of the way that we’re going to get out of [this stagnation] is the agenda that the president is laying out, and the important role that the federal government can play in driving broader scientific and technological discovery.

To me, one of the biggest reasons why we as a country will succeed is because of the innovation that we can have in science and technology. There’s a very deep and rich history of the federal government in the United States being part of a larger innovation ecosystem.

The challenge that we have faced over the years — and one thing that we think a lot about at this office — is the changing nature of where early-stage, basic pre-competitive research and development happens.

If you go back to the era post-World War II, the vast majority of R&D was being funded by the federal government. Over the last 70 years, we’ve had this inversion where now the majority of R&D is funded in the private sector. We have to ask ourselves every day: what role does the federal government play in a world where the private sector is investing more than any time in history in this research and development?

The biggest example, the one that’s screaming in our face every day, is with AI. You look at these numbers, the types of investment that are happening in infrastructure and R&D that’s supporting the AI revolution. Even for many of us that are deeply immersed in tech, and have been for decades, these numbers are crazy. They are truly unbelievable levels of investment and it doesn’t seem like it’s stopping. Every week there’s a new big one. Policymakers like us here in Washington have to sit back and say: “There are billions, if not trillions of dollars being invested by the private sector in AI, but what role can the federal government play?” That’s the same type of question we ask for any of these emerging technologies.

Going back to the speech, the point was that there always will be a very important role to play. The government has to make that choice to say: “We do not accept that stagnation. We want to work hand in glove with the private sector to make it happen. There are levers that we control which can make a big difference.”

You were confirmed as the director of White House Office of Science and Technology Policy (OSTP) in March. Since then, you’ve tackled a whole bunch of things: science, drones, supersonic flight, quantum, energy for data centers. You rolled out the AI Action Plan in July. Give us the high-level takeaways.

It all began on the third day of the administration where President Trump, signed an executive order revoking the disastrous Biden executive order on AI, and essentially gave us a 180-day shot clock where myself, Secretary Rubio, and David Sacks were on the hook for delivering the national strategy for the US, called the action plan. We delivered it in July. That was launched at an event here in Washington. At the same event, the president signed three executive orders [on permitting data centers, preventing woke AI, and promoting the export of American AI] that generally mapped to some of the priorities in the plan. But the vision essentially laid out in the plan has three core policy thrusts, or main pillars:

The first is the US has to continue to out-innovate and continue to be the leader in AI innovation. There’s lots of work in there around regulatory issues, around R&D, and we can get into those.

The second is the US has to lead on AI infrastructure. This revolution is going to be powered by electricity and by data centers, and we have to have those built in the United States as quickly as humanly possible. There’s a lot we can do to accelerate that process and get the government out of the way as we build that infrastructure.

The third is the importance of exporting American AI — essentially creating an ecosystem globally that is reliant on American technology. Lots of projects are being launched on that front as well.

Thematically, that’s the core themes of the action plan. There are almost 100 actions enumerated in it, but they generally fall into those three buckets. [For more on the detail of the action plan, Statecraft recently interviewed its lead author, Dean Ball.]

Let me ask you about that third bucket, export. One of the flagship programs of the action plan is this export promotion program, which provides financing and assistance to promote the adoption of the US AI tech stack overseas. The admin has also talked a lot about AI sovereignty — about not wanting global governance for AI, wanting each country to be able to develop its own roadmap.

Are these two things in tension? Do we want every country to have full AI sovereignty? Do we want the US tech stack to dominate in certain areas? How do you think about balancing those two priorities?

I think of them in concert, not in opposition. For us, the core challenge we’re facing — maybe if we zoom out and think a little about how we got to that third pillar, it came out of a lot of work that we did in Trump 45 around telecom. If you think of that era, the first big rollouts of 5G happened at the tail end of Trump 45. We, as a country, found out pretty quickly we were in a tough spot. We had no American manufacturer of advanced telecom kit. There were two allied partners, it was Nokia and Ericsson that could provide those. Then you had an upstart which was pretty good, which was Huawei. In the early days of that challenge, one could argue that the Huawei technology certainly was inferior to the US technology, but nonetheless, because of the heavy subsidy by the People’s Republic of China (PRC), they were able to aggressively go out and get their kit all over the Global South and even deep into the networks of some of our partners and allies.

Me, as the CTO of the United States and kind of our tech minister, was left running around the world talking to my counterparts, trying to convince them to either rip and replace their Huawei or make the expensive decision to buy Ericsson or Nokia. There were a couple of lessons that I learned out of that. The first was that just because you have the very best technology doesn’t mean it’s going to be adopted. Price does matter, and the buyers are ultimately going to be quite price-sensitive, especially if at the end of the day you can get pretty much the same service by someone else. That created a very interesting national security problem for the US, where a lot of these networks could potentially be compromised and could have back doors, back to the PRC.

If you fast forward to where we are today, one could argue that the export of American AI is arguably even more important than telecom, in the sense that the models of choice, and the stacks that are used around the world, are going to be critically important in the way that lots of governments and economies function. The ultimate software that is used to power healthcare services, to run tax services, to essentially be the platform in which all governments run all their AI services is really, really important. You want to be in a position where American models are ultimately the ones that are fine-tuned to run all these applications.

Now the advantage we have, and what’s different than before, is that we actually do have the very best technology. I think China at the moment is actually quite constrained in their ability to fabricate enough chips for export. The ones that they do fabricate domestically, there’s more than enough demand internally. There just isn’t enough excess to export. So we have this window of time — in the next year or two — where we truly can be the single powerful supplier of the totality of the stack, meaning chips, models and applications. The other advantage we hadn’t before is we — America, our companies — are leading in all three layers. We have the very best chips in the world, the very best LLMs, and the very best applications on top of it.

The thesis of the program is: let’s try to bring all those together, make turnkey solutions that countries around the world can easily adopt and implement, and do that as quickly as possible, so that we can start creating these networks and ecosystems where developers, countries, and governments around the world are all using American technology.

You described this year-long lead time that we have as a result of the lead technologically. What does that mean for you in this role over the next year or so? You’re doing a ton of travel, a lot of international diplomacy.

The president signed the executive order in July of this year. There’s a shot clock at the Department of Commerce to stand up the program in the next week or two. You’ll see some announcements out of Commerce coming soon. Then the ball is ultimately handed to a committee [the Economic Diplomacy Action Group] that’s led by the Secretary of State, that includes the Secretary of Commerce, me and a few others, to go out and do the export early next year.

We want the world to know that America is open for business. We want the world to be running on our technology stack, which we think is the best — and we want to go out in the world and tell them that. I was at the Asia-Pacific Economic Cooperation Digital Ministerial in Korea a few months ago where we shared this message and we essentially said that, “The US is open for business. We do want to sell you chips, and we deeply believe that the ideals and the priorities that you have as countries ultimately are ones that are aligned with the US.”

It goes back a little bit to the sovereignty question — I didn’t quite answer it, but to answer it: the reality is we have a stack which can answer the mail to the priorities of individual countries. If you’re a country and you have sensitive government data, you obviously don’t want to be running an AI system where there’s an API call to a foreign country, even if it is the United States. We understand that, and the hope is that we can design a system, with the great technology companies we have today, which can allow them to operate American software in a way that ultimately is able to meet whatever standards they have in-country.

You and I talked about a year ago, before the election and this role, and you were reflecting on the balance during the first admin between “protect” actions and “promote” actions: protecting the American tech industry and promoting the tech stack abroad. We talked a little bit then about trying to get Huawei technology out of the infrastructure of our allies.

Tell me how you’re thinking about the protect side of things.

In the last couple of weeks, the Secret Service uncovered this massive telecoms hacking network in New York City.

Earlier this week, a former National Security Council staffer in the George W. Bush administration was arrested after the FBI raided his home and found thousands of top-secret Air Force documents that he’d been passing along.

This week, the British government admitted Chinese hackers have been inside the UK’s classified network for over a decade.

Given these stories, how are you thinking about the task of protecting American infrastructure?

It’s a little bit of what you said, and it’s a lot about the world of exports and constraints for some of our adversaries from accessing our highest-end technology. On one hand, there’s an incredible amount that we need to do to secure our critical infrastructure. We have a new National Cyber Director here at the White House that’s very focused on that, along with the folks at the Department of Homeland Security, and we need to be very vigilant in tracking the type of hacking that ultimately happens by a lot of our adversaries. We see it all the time, and it’s disheartening, but we’ve got to do better.

On the more “protect” side of technology, a policy that we’ve maintained and kept in place is — particularly in the world of AI — our most high-end chips are ones that we are limiting the ability for adversaries to have access to. That’s something that had started as early as the [first] Trump administration where we put export controls on some of our advanced lithography equipment, which ultimately has paid big dividends in limiting the ability of the PRC to develop high-end chips. That will continue. Finding that balance of needing to promote as much as possible — get American tech out there — and also rate-limit our adversary on the very high-end stuff is the general strategy.

Tell me about the data center build-out work that you’re doing. Folks will be aware there’s a huge need for energy if we want to build this out domestically, and that this admin cares about that. But practically, what are you and this admin trying to do over the next year to make that happen?

Our second pillar of the strategy is, how do we accelerate our ability to build both the data centers and the power capacity? It’s a very tricky and interesting problem. There is one part that’s federal-government-related, and there is certainly National Environmental Policy Act (NEPA)-related things you have to get through and other types of federal permitting. [Statecraft previously discussed the impact of NEPA.] That’s the stuff that we as a government have a lot of control of.

The president directed in his executive order on AI infrastructure that we need to, as quickly as possible, accelerate that effort to remove those barriers and make it much easier to get your adjudication done on approval or not for your projects. That’s an ongoing effort, and we want to make it as easy as possible, essentially a one-stop shop to come to the government and say, “Look, I want to build this AI infrastructure, help me get all the necessary permits and approvals,” and we can help you do that. That’s in the works.

The second piece, which is a little trickier, is state and local. If you talk to a lot of people who are building data centers and trying to do the energy build-out, a lot of the bottlenecks end up at the state and local level. We’re trying our best to liaise with a lot of state governments to try to make it clear that this is a priority for their country. They as a state can benefit if these build-outs ultimately happen.

The third piece around that — of things that the federal government controls — is we have our own real estate. We have federal lands, which can be used for build-outs themselves. Many of you may have been tracking the Department of Energy program. The Department of Energy has already announced four locations for build-outs of data centers. That’s already underway. We did that in the first six months of the admin.

What policy levers do you have at the Office of Science and Technology Policy (OSTP)? Folks who are interested in the executive branch will know OSTP doesn’t have the formal statutory power or the budget that other Cabinet-level roles do. It has this convening power, and you’re an advisor to the president. It has all kinds of power that are not formal or statutory.

But as I understand, you have a fairly small team compared to other parts of the executive branch. In his interview with Statecraft, your former colleague Dean Ball described it as the “little brother” to the National Security Council, especially on tech-related issues. Two questions:

1. How does implementation work on the AI Action Plan when you don’t have all the levers that, say, the Department of Energy does?

2. Between Trump I and Trump II, have those balances between different organs in the executive branch changed at all?

Maybe there’s a slight misunderstanding. [NB: I am not sure to what misunderstanding Director Kratsios is referring.] In the Executive Office of the President (EOP), there is no component which has any budget to really do anything. The EOP is designed by law to be an advisor to the president, and a convener to drive interagency policy on a variety of issues. Generally [you have] councils at the White House which drive different policy — you have an economic council, a domestic council, a National Security Council, and science and tech [managed by the OSTP]. Each of those has their own category of work.

In Trump 45, science and tech was exclusively at our office. The Biden people made the choice to absorb some of the tech effort at the National Security Council. In Trump 47, it’s all back in the office that has statutory authority over it. But what’s key for us… is that it’s a federated approach to science and technology policy. Almost all of my counterpart tech ministers or science ministers around the world have a single agency that attempts to do everything on their own. They have one person that tries to decide the best way to deliver on whatever the mission is of that country.

In the US, we’re blessed — and sometimes it’s a little challenging because you’re wrangling people — with having lots of agencies that do different aspects of the larger S&T portfolio. At the Department of Energy you have all the national labs: almost $10 billion in spending just under the Under Secretary of Science that runs the labs. You have the National Science Foundation, which is basic research, in the neighborhood of $9 billion. There’s the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration, that does everything related to weather and weather satellites, at the Department of Commerce. There is the National Institute of Standards and Technology that does all the standard-setting. There’s the United States Geological Survey that does our geological surveys. There’s NASA.

The most exciting meetings for me are when we convene our NSTC — National Science and Technology Council — and all of the heads for all science agencies come to the White House. We’re able to ultimately chart out: if we want to drive US leadership in AI, or quantum, or nuclear, or 6G, everyone has a piece to play. There isn’t one place that’s singularly responsible for that. Each individual agency has a piece of the puzzle.

You talked earlier about lessons from your time in the first Trump admin with the Huawei wars. What other lessons have you brought from those first four years? I’m curious especially for differences: how does this admin look differently from the first Trump admin?

The main thing I’ve generally seen is that the issues which our office and the president were championing in 45 have become far more prominent in 47. The example I always give is the event we had for the signing of the executive orders and the release of the action plan in July. At that event, I spoke, five cabinet secretaries spoke, the president gave a speech for half an hour on AI. It’s incredible. When we want to drive an effort on a topic like AI, the challenge we have is that everyone in the cabinet wants to participate, be part of it, and bring the muscle, power, and statutory authorities associated with their agencies to bear on the issue. That creates an incredible opportunity.

One thing that’s changed culturally between 2016 and today is, a lot of folks might be familiar with this idea that it’s easier to get your ideas in front of people in positions of authority, that there’s more of a horizontal information flow. In the past week we’ve seen colleagues of yours like David Sacks and Sriram Krishnan engaging on Twitter with small posters about these big ideas. What’s your media intake like? Are you experiencing this horizontal dynamic? Are you lurking on Twitter?

We try to connect with all Americans as they share great ideas with the White House. As you mentioned, I have amazing people on my team, that work on our AI staff, that are absolutely terrific in driving that and being very good. One of my former analysts, Dean Ball, was probably one of the most terrifically connected people in the Valley. He served as a great avenue for lots of people to bring ideas to the table. I think those were ultimately manifested in the Action Plan.

I think you’re actually right. People are more engaged in having conversations with Washington — and our office and the White House more broadly — on tech policy by many multiples than they were in 45. Obviously it’s a consequence of these much bigger issues being much more front-burner. But at the same time, the way that the media landscape has changed and the way that people communicate — it’s much better information flows, and ultimately the policy ends up in a better place. If you try to do a lot of this stuff in a vacuum, it obviously doesn’t end well.

What about talent flows? As a public figure, you’ve talked about some of the challenges and opportunities of getting more technical talent into the government. In this administration, at senior levels, there are a lot of tech figures who have come in, including some of the people we just mentioned. Are you seeing that technical talent also come in at lower levels, or are there opportunities or places where you’d like more technical talent to be entering the government currently? Any call to action for this audience?

I’ll be honest: if I was going to rank places where I wish we could do better, I would rank this one pretty highly. It continues to be a real challenge. The rules and regulations around bringing people into government haven’t changed [Statecraft recently discussed how to improve government HR with Judge Glock]. A lot of those are in statute, and it’s continually hard to get people in. Scott [Kupor],1 who runs the Office of Personnel Management, came from Andreessen. I think he’s spending a lot of time thinking about this issue, and hopefully we’ll have a lot more to talk about soon. Our hope is to try to find ways to bring more people into government.

We’ve chatted ourselves about: are there ways that you can do rotations or find ways for people to know that they’re time-limited? They can come in then go back to the job they had, or find easier pathways to flow in and out. I see it every day as I try to assemble my team. Very talented people — if you come work in my office, you can’t hold any equity in anything related to tech. A lot of talented people have spent a lot of years building large venture portfolios or having worked at companies, and asking them to divest of all that is a really big ask. I totally understand the rules and it makes sense that they’re there, but you can imagine that there are challenges. So my hope is that we can continue to bring great tech talent in, and we need it more than ever.

Talk to me about this admin’s vision for science, because we’ve spent a lot of time here on AI, but you’ve spent time in the public eye also making the case for higher standards for scientific work.

As many people in this conference know, the federal government has been funding basic research for many years. It all started with Vannevar Bush when he released “Endless Frontier,” and that led to the creation of the National Science Foundation. I think what’s really important for the government to always remember is, we have an obligation to the American people to spend that money very wisely on research that is in the public interest. and is of the highest possible ethical quality.

The president signed an executive order around gold-standard science. Within that executive order — you guys can look at it — general tenets of things like reproducibility are in it. We want to create an environment where the research that the government funds is one that is of the highest standard, the highest caliber. When we shared the construct of all of these core tenets in gold-standard science, it was quite comforting, because everyone essentially was like, “Yes, we want this. This is what we believe as scientists. We want the work that we do to be highly defensible, something that we can be proud of, showing that we have followed the scientific method.” That’s something that’s being implemented across our agencies quite rapidly since the executive order was signed.

But the larger question that comes about around science more broadly is: are we spending our taxpayer dollars on the right things that are in the national interest? I think in the early days of the administration, what we identified and what was exposed was that hundreds of millions of dollars was being spent on bad science — on things that most American people would not want their taxpayer dollars spent on. That correction was necessary and important. We can get to a better place where we’re driving the next great discoveries here in America. Back to your question of [how] have we achieved stagnation? The dollars that the federal government spends are going to be an important part of getting us out of that rut. If we can focus them in the right areas and spend them in the right ways, that’s how we can make a difference.

As part of that executive order, and more broadly on the science agenda, one thing is the mechanisms by which we disperse federal funds. We have been on this autopilot mode, where the same methodologies of choosing which grants and who to fund have essentially been stagnant for many, many years. The reality is, there’s lots of ways to give out money. You can do fast-track grants that allow you to quickly make decisions — rather than waiting months. There are private sector organizations that could be recipients of federal funds that typically would go to, let’s say, universities. There are other ways to do science than the exact ways that have been done in the last 30 years. That could be a big driver and supporter of greater innovation in the US.

Will you say a little bit more about that? New institutions of science, like the Arc Institute or focused research organizations, is that the sort of thing that your office is considering?

Precisely. These focused research organizations are ones that can be doing incredible work and they should have access to the competitions to be able to access federal dollars. As a government, we should be laying out what the priorities are of the United States, and whoever’s best suited to do the science and research to deliver on those priorities should be the ones that are funded. Universities do not and should not have a monopoly on doing basic research funded by the federal government. There’s lots of amazing institutions out there that do that.

If you look at who is funding basic research over the last 10 to 20 years, you’ve seen this incredible growth in the philanthropic focus on basic research. Folks like the Simons Foundation and many others are doing incredible work in funding basic mathematics and lots of other work. Again, I say this too many times, but it’s true: we have to understand as a federal government, where do we sit in the landscape of the broader funding community? If philanthropy is doing X and the private sector is doing Y, what is Z that the federal government should be doing, which can fill a gap that is not currently taken by the private sector?

Back to your point, there are lots of other models. I would love to get a readout from your conversations [at the Progress Conference], to be honest. Send that to the White House. We are trying to figure out the best way to activate our science enterprise and recharge it as quickly as we can.

Let me ask you about the university side of this. Obviously there’s a lot of enthusiasm here for other kinds of science-funding institutions. The OSTP head in the first Trump administration — your predecessor, Kelvin Droegemeier — has been working with universities to have this conversation about how university indirect costs and these grant systems work. What do you see as the opportunities for universities to work collaboratively to reform how science is conducted or funded?

When I talk to university groups, I think the agreement that I tend to always see in the room is that no one believes that the current F&A [Facilities and Administrative] — or overhead cost regime — that exists today is one that would exist if everyone was given a blank sheet of paper and said, “Come up with the right way to do this.” Everyone knows it’s broken. Everyone knows it’s wrong. [IFP has looked at how indirect cost recovery works, and possible reforms.] The other thing that everyone realizes is it’s not trivial to fix it. Because of the high activation costs of fixing it and aligning it correctly, people have not wanted to deal with it. The lobby has been strong enough to essentially beat down any efforts to change it.

Luckily, we have a president that isn’t affected by that and is willing to make the important and necessary change to actually bring some level of sanity to the way that F&A is calculated and paid out by the federal government. At the end of the day, whether they say it publicly or not, private universities know that the current system is wrong and they’re working behind the scenes to figure out the best way forward. I think what Kelvin did, and what the group presented as a whole was — the reason they even did the report was a concession that the status quo didn’t work.

We are taking their recommendations and our team at the Office of Management and Budget here and others are working through what the final policy will be. But at the end of the day, both taxpayers and universities are going to be much, much happier.

We’ve spent a lot of time on AI and a little bit of time on science. For the intersection there, how are you thinking about the federal government’s distinctive role in getting science more ready for AI?

This is probably what I’m most excited about when it comes to the future of our AI agenda. It is this intersection of AI and scientific discovery. Artificial intelligence is going to be probably the greatest unlock for science in the history of the world. This is a technology which will accelerate the way that we’re able to make scientific discoveries more broadly. What’s most important about this is how we get there. How do we get to a point where we can leverage AI to drive scientific discovery?

I’m very heartened to see a lot of private-sector companies are jumping on this. OpenAI had some great announcements about it very recently. Google just had an announcement a couple days ago — obviously they did a ton of work in years past on things like AlphaFold. But the question that we ask ourselves again is: “What role can the federal government play in it?” One thing I always think about is the incredible amount of scientific data that the federal government has, that’s valuable in training large language models (LLMs) for scientific discovery.

At the end of the day, a lot of LLMs are trained on what’s out in the open internet. A lot of the code-specific LLMs are trained on code that’s out there, but the science LLMs can be trained on science data, and that’s far more siloed and not necessarily in the public domain. There’s a ton that places like the Department of Energy and even the Department of Commerce — there’s data there that can be tapped into to drive the science.

Michael, I have to ask: we’re at Lighthaven. The folks who are hosting us tend to have a more worried view of the trajectory of AI than some of the other participants here, or you. What would you say to them about this admin’s approach?

You have no administration that has been more committed to delivering the benefits of technology to the American people than this one. Between me, the president, and the broader cabinet, there is a deep and fundamental appreciation for the value that technology can bring to changing the lives of Americans for the better. As we write in the title of our report, we are in an AI race. The reality is that pretending that there aren’t other people out there that are developing AI that is in very stark difference to our approach and our values is something we can’t ignore.

We can’t live in a world where we believe that we can fully control what happens here, and the rest of the world is going to play along. What we need to do — and that’s why the AI export program is so important — is share this great American technology. All our great companies think very carefully around how this technology is going to be developed and how it can be developed in a way that benefits all the American people. That’s the type of technology that we want the rest of the world to be using and running on. There are a lot of perils if we don’t do that.

I’m extraordinarily enthused about the benefits, and I don’t want to wake up in 20 years, when my kid’s about to go to college, and think to myself, “Wow, I wish we could have done more to make sure the US was leading,” because this is so important for the country.

Our transcript initially identified Scott Kupor as Scott Bessent, the Treasury Secretary — we regret the error.