Today we’re joined by Judd Devermont, one of the most experienced Africa policy hands in Washington. He spent 16 years as an intelligence analyst, serving in both the Obama and Biden administrations. Most recently, he was Senior Director for African Affairs at the National Security Council. He authored the Biden administration’s Strategy Toward Sub-Saharan Africa. Since leaving government in early 2024, he writes a newsletter called Post Strategy, reflecting on what works and what doesn’t in US policy toward Africa.

This conversation is about the mechanics of diplomacy: how US engagement with Africa actually works, and why it falls short. Judd explains diplomatic “care and feeding” — the constant effort required to maintain relationships with African countries, while competing for presidential attention with Europe, the Middle East, and Asia.

I wanted Judd’s perspective on American goals for diplomacy in Africa, but also his honest appraisal of where the administrations he served in failed to execute, and what he wished he’d done differently. Why do presidential initiatives in Africa fail so often? Does the National Security Council deserve to be cut down to size? Why do CIA analysts have such a high opinion of themselves, and is it warranted? How should you negotiate with a military junta?

We get into all this and more, and Judd was very game to argue with me about all of it.

We discuss

What “care and feeding” means in diplomacy

What went wrong with the relationships with Niger

The problem with envoys

Whether the NSC has been neutered under Trump

Why most intelligence analysis doesn’t cut it anymore

Thanks to Harry Fletcher-Wood, Katerina Barton, and Rona Fe Cruz for their support in producing this episode.

For a printable PDF of this interview, click here:

I want to start with a thought experiment. Let’s imagine that you get to reallocate American diplomatic resources globally. You’re being asked to rebalance how much focus, attention, and touch different regions get, but you’re not allowed to increase the total amount of diplomatic resources or staffing. Do you put more resources into Africa? If so, from where do you pull them?

It’s hard for me not to say, “Put more resources in Africa,” so I won’t be provocative or disappoint. Currently, I don’t believe we’re doing enough for our national security interests, based on how much effort and time we put into Africa. I experienced this throughout my career as an intelligence officer in the Obama and Biden administrations. There come times where we are at a crunch point and someone says, “We need to get the Africans on board,” or, “How can we work with the Africans on this critical issue?” Or there’s a problem that’s developing in Africa and it’s in our interest to be able to resolve it. We haven’t done the legwork, because we said that Africa as an area of focus is near zero, and I think that’s really problematic.

Let’s pretend that the value of Africa is X. I would bump it up by 10 points and give us the opportunity to have that grow as the continent becomes more significant. Then I would question, “Do we need to put as much effort in parts of the Global North, like Europe, as we do?” There’s too much legacy in the investment in Europe and not enough investment in where the bulk of the population of the world is, which is in the Global South.

Would the counterargument to that be our European allies matter a lot more for our national security interests than our friends in Africa?

We have an extraordinary amount of alignment with the European partners already, or at least we certainly did pre-Trump. So some of the care and feeding that we do with the Europeans, and the endless amount of touch points and high-level meetings that they get, are probably unnecessary to have the same outcome.

Meanwhile, the kinds of investments we need to make in Africa to have outcomes that are in our interest are insignificant. Meanwhile, many of our allies and adversaries are spending more effort in Africa. They are getting more trade, and alignment in international forums. They are getting the benefit of voices supporting their positions and their vision of the world. I’m not discounting the importance of France or Great Britain. What I’m saying is that you probably don’t need to put as much effort into those relationships for the same results. If you don’t put more effort into our partnerships with Africans, we are going to miss out in the future.

I like the phrase you just used: “care and feeding.” What constitutes care and feeding in a diplomatic relationship?

What we’re mainly talking about is senior-level engagement. Who gets to go to the White House? Who gets a visit by a senior US official? For too many countries in Africa, the most senior US official they will ever meet is the ambassador of that country. If you don’t have a peer-to-peer relationship with Africans, it is going to be to your detriment.

I’ll tell you a story from a couple of decades ago. President George H.W. Bush was trying to cultivate [UN] votes ahead of the Persian Gulf War against Saddam Hussein. Côte d’Ivoire [also known as Ivory Coast] was on the Security Council, and the foreign minister of Côte d’Ivoire, Amara Essy, comes to Washington and meets with Secretary Baker. Essy says, “I’ve been to Washington countless times, and until today, I have never met with anybody higher than the assistant secretary of state.” Baker, to his credit, was like, “We will change that. Next time you are in New York or you’re here, I will meet with you. I’ll come up to meet you in New York, or I’ll bring you down by train.”

Here we were, at the precipice of a critical vote and the foreign minister of a country had only met with — an important figure in African policy, but in the scheme of things, not a very senior official. Think about the other way: what if the US president, or Secretary of State Blinken, went to an African country and they said, “You can meet with this guy in the middle of the Ministry of Foreign Affairs, the desk officer for the US.” That’s what I mean by care and feeding: accruing mutual respect to people who are your equals.

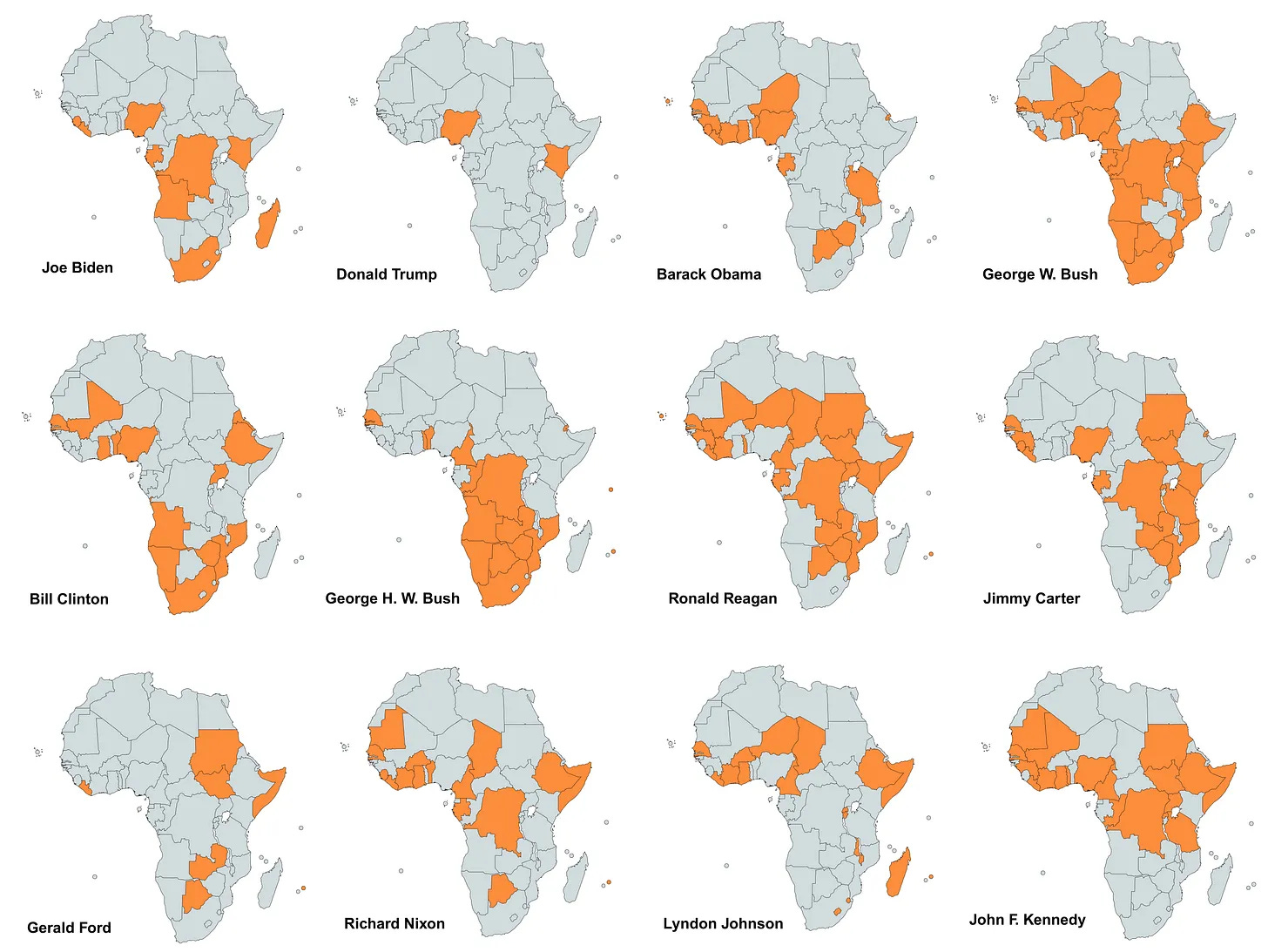

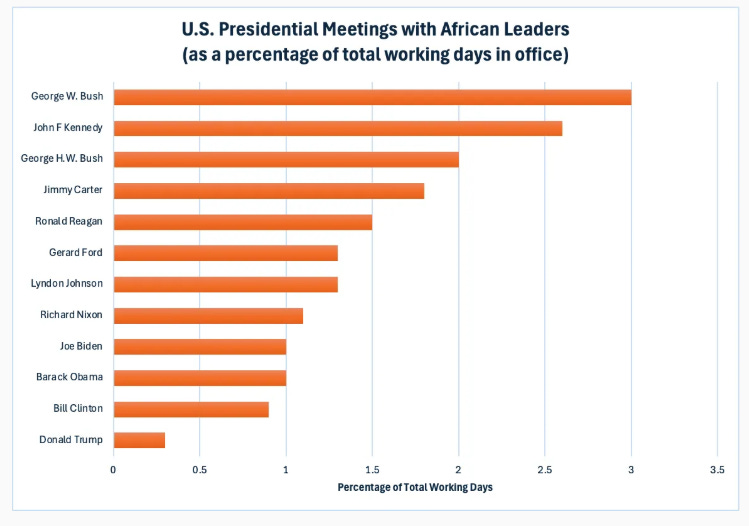

Of the five most recent presidents — I learned this from your Substack — only George W. Bush spent significant time with African leaders. Presidents Clinton, Obama, Trump, and Biden spent far less time with African leaders. Compared especially to JFK, Nixon, Reagan, H.W., Carter, modern presidents spend less time on Africa. Why is that?

President George W. Bush was remarkable in the post-Cold War era with how many African leaders that he met with. I have found in my research that that’s correlated with a whole bunch of different things, including major development programs, travel, consultations on the biggest global issues. A lot of this goes credit to President Bush, as a leader. But also I found a nice quote from him that said Condoleezza Rice told him when he took office, he’s going to be spending more time with Africans and with Africa. And he really did that.

A colleague of mine told this story to me: President Bush met with President Museveni of Uganda. President Bush asked Museveni about his views on the Iraq war. Later he was asked, “Why did you bring up the conflict in Iraq?” Bush said, “I read his bio. He was an insurgent leader, and we’re leading a counterinsurgency. I wanted to get his firsthand insights.” I love that story because there he is, not just doing African issues with President Museveni, he’s talking about the biggest topics that are top-of-mind for him. That’s phenomenal.

You asked a bigger question: why has there been less engagement from the post-Cold War presidents vs. the Cold War presidents? For the most part — outside of George W. Bush — I don’t think that there has been a real connection with why Africa’s important. In the Cold War — this is crazy — President Kennedy spent 25% of all foreign leader meetings with Africans. He truly believed that if we were going to shape the Cold War and the international order, we had to be working with Africans. Not only did he engage with Africans, he established USAID and the Peace Corps. For me, those two presidents stand above all the others.

You worked in the Obama and the Biden administrations, different roles, but both pretty senior, focused on Africa issues. In terms of meeting its own goals on Africa, which of those two administrations was more successful? Which of them executed better?

That’s really hard. I feel conflicted loyalties. I’ll tell you what I thought was a strength of President Obama’s administration on Africa and I’ll tell you what went right with President Biden. For President Obama: not just his own background in connection to Kenya — I don’t even think that’s relevant here. He had a bunch of senior leaders in the Cabinet who also thought Africa was important:

National Security Advisor Susan Rice had been assistant secretary for Africa.

Head of USAID Gayle Smith had been a senior director for Africa [on the National Security Council] in the Clinton administration.

Samantha Power, in New York, had spent time thinking about Africa.

That allowed us to do some big programs, like Power Africa, or the Young African Leaders Initiative, or decide that we are going to send the military to the West Coast of Africa to deal with Ebola over anyone’s objections. Those were the things that were working in the Obama administration.

Sometimes there was a little too much preachiness about Africa, and in ways that — we don’t do it anywhere else in the world. We have complex, complicated relationships with India, or the United Arab Emirates, or Vietnam, and we don’t do as much lecturing. But the Obama administration in Africa, there was a little too much of that.

In the Biden administration I think we did less lecturing. But we did less engagement. I’m proud of a lot of the things that we did, particularly in terms of, “How do we get Africans to have a bigger voice in international forum?” Getting the African Union to join the G20, calling for African seats at the UN Security Council. But I don’t think there was enough of an echo chamber around President Biden to break through — to get the engagement we needed on the continent. Also, the war in Ukraine and the conflict in Gaza were huge sucking sounds, and they really strapped the bandwidth. I do think that Jake Sullivan and Tony Blinken would [have done] more on Africa, but they were pretty limited given how much those two particular conflicts, as well as competition with China, was limiting the space for other engagement.

While prepping for this interview, I asked quite a few people — from the Biden admin and from outside — about their views on the Biden admin’s engagement on Africa. They didn’t all line up, but a big theme was the admin was blindsided by how much time was taken up by Ukraine and Gaza.

Maybe there’s one more point, Santi, on the rhetoric. Those of us who focus on Africa, in some respects, often we write checks that we can’t cash. We hope that we can cash them. We write them down so that we can use them as a bludgeon, to push people to get to them. But at the end of our administration, we’re stuck with some very aspiring rhetoric about where we want to take the relationship, and then the reality that we didn’t meet that. Partly that was because we couldn’t drive the system to get to where we had hoped to be at the end of the day.

You said a moment ago the Biden admin was less “preachy” in its engagement with African countries. But people who follow Africa policy will remember that in March 2024, Niger’s military junta ordered US troops doing counter-terrorism work to leave the country. The decision came after what the junta called a “condescending attitude” from US Assistant Secretary of State for Africa Molly Phee during an American delegation’s visit.

You worked with Phee. What was your read on that encounter?

I left the administration in February of 2024; the Niger coup had happened in July [2023], and I was in a number of meetings where we knew that we had to engage the junta about the direction that they were taking. We wanted to see a pathway back to democratic rule — although we were flexible about how long that would take, we wanted it to be a conversation. We had this outstanding issue about the future of our military bases, both in the capital and in Agadez, and some concerning information about our foreign adversaries. I can’t speak to what happened in that meeting, because I wasn’t there. I do know the intention was to say:

“How do we find a way forward together? We’re under our own domestic constraints, as much as you are as the junta: in terms of things that you’re promising your populace, or the justifications you’re giving for your coup, and your dissatisfaction with a number of relationships that you have. How do I identify the things that are making it even more difficult? Is there a way forward on that?”

That was the intent of the conversation.

What is missed sometimes in the public conversation is that we weren’t saying, “Don’t have a relationship with Russia.” We were trying to be very specific about the things that would be concerning to us — considering that we have military bases and operations in Niger — there may be certain types of weaponry that the Russians want to provide, or access the Russians want, that would be problematic for our ability to maneuver. We actually had more flexibility and openness to thinking about these arrangements than sometimes is given credit. We wanted to understand what their ultimate trajectory was towards democracy; what was going to be the final disposition of the former head of state, Mohamed Bazoum, who is still, to this day, under house arrest.

But when I left in February, our goal was to have this conversation in person so we can figure out a way forward. Let’s express our concerns and where we think we can partner. I don’t think that is paternalistic. Again, I don’t know what happened in that meeting. Obviously the outcome and the perception of that meeting is not very good, and it’s not where I would’ve liked us to be.

I’ll tell you that’s the conversation that I had when I met with the coup leader in Gabon. I led the delegation. We talked about the things that are important to us and to them: “Can we find a way forward?” We largely have; they’ve transitioned back to civilian rule. The military junta leader is now the president, but they did it in two years. It’s faster than any of the countries in the Sahel, and we’re having constant engagements with them. The relationships with Niger, Mali, and Burkina Faso — it’s a much slower process and there’s a lot of hurt feelings on both sides perhaps, and a lot of sensitivities.

You’ve written about the fights that happen over when the US should engage with foreign leaders. There are always forces who will push against the idea of senior officials meeting with a country’s authoritarian leaders. Then there are folks on the realist side who will say, “The US has an interest in sitting down with these people, even when we have lots of disagreement.” How have you seen that dynamic play out?

There’s two villains here. Villain number one is the generalist who says:

“Africa’s too complicated, just give me the good news stories. Let’s have the heroes, the saints, the countries that represent values that we cherish. Let’s have them have the meetings, so they could stand up as some sort of exemplar or totem of what we want to be. These countries that are really complicated, these leaders that have past that we don’t agree with, let’s not spend time with them.”

That’s the generalist side and I’m talking about both politicals and civil servants.

On the other side, there’s the Africanists who also play this game, who just want us to make sure that we’re rewarding good behavior. I had a meeting with an ambassador who told me, “Why are you guys even considering a meeting with that guy? Don’t you know how bad he is? You should be meeting with my leader from my country.” Instead of an argument on the merits of what the problems are that we were going to address in the Oval Office, he was trying to figure out who had more virtue, which is crazy.

That’s a dynamic and I’ve seen it play out so many times where, even when you have US presidents who aren’t spending a lot of time on human rights issues, people below them will say, “Should we really be engaging with this leader? I read a Human Rights Watch report, or this cable, and it looks like they’re pretty bad.” I would pull my hair out — I don’t have much hair, but what I had — because the day before that, the president engaged with a leader from the Middle East, or Southeast Asia, or Latin America, who had an equally torrid past. There’s a lot of double standards in the African engagement space. It’s not to our benefit.

One last point, because it gets back to how many leaders that you have in the Oval Office. This is where I did have a problem. If I was only going to get four African political leaders in the Oval Office — if I was only going to be allotted one or two a year — then I was going to pick Nigeria, South Africa, and Angola, or Kenya. I didn’t have the luxury of saying, “Let’s bring in a variety of leaders,” in the way that President Bush or Kennedy did. That is one of the challenges when you’re only given so many slots — it’s never explicit — then you are being more careful. You’re not only trying to get the most strategic countries in there, which is a good thing, but you’re not willing to take the risk of having the country and the leader who you’re going to get a lot of hell from the Hill from, or from activists, or the bureaucracy. That’s the third dynamic that I want to be confessional about.

In what implicit way are you told, “You only get so many slots”?

A couple of things happen. Sometimes, after you have a big meeting like the Africa Leaders Summit, you’re told, “Don’t bother us for a while.”

By who in the Executive Office of the President?

Sometimes it’s by the people who run the access to the president, or people who have to rack and stack all the foreign leaders. “You had a great event. I’m very thankful that we had that event, but take a beat for a little while.” That’s one of the ways it’s done.

The other way, which is a little more subtle, is, “We put this list together. Your country was on it. It didn’t make the cut line. We were told we didn’t have ten, we have five, so you dropped off.” You start realizing that you’re only going to get a couple of these, at least in my experience, and you’re going to have to be persistent about it. One of the things that I did as a trick is that I would send a request. I would be told, “No.” I would send a second request. I would be told, “No.” Then I would say to myself, “I’m really uncomfortable that I keep asking for this, so I definitely need to do it one more time.” You just have to keep pushing and try to keep refining the arguments and not give up. You have to be that pain in the ass. But maybe in retrospect, I needed to be a bigger pain in the ass.

In your newsletter, “On engagement,” you said that at times you had to tiptoe around big events to make sure that you didn’t have the wrong encounter between Americans and an African political leader. You had to “choreograph an elaborate two-step” to keep the US delegation at arms length from the Zimbabwean president at this big council event in 2023. I want to know about choreographing that two-step.

So the Corporate Council on Africa (CCA) — which is not a US government institution — has an annual business forum. Sometimes they do it in the United States, sometimes in Africa. They just did one in Angola, next year it’s going to be Mauritius. In 2023 it was in Botswana. The council and the government of Botswana work together to decide who’s on the invite list.

Because Zimbabwe, which is Botswana’s neighbor, is part of a larger regional grouping called the Southern African Development Community, they were on the list. They were there for the 2019 summit in Mozambique, we were all fine with that. There’s a sanctions program on Zimbabwe, and there was an uproar by different parts of the federal government legislative branch about the fact that a sanctioned individual, the President of Zimbabwe, was going to be there.

Even though it’s not a US-hosted event?

We would’ve done a family photo where the US delegation and the African leaders stood together. We could no longer do that. There were a whole bunch of other things that the CCA had to do. The “Investing in Zimbabwe” breakfast couldn’t happen any more. The President of Botswana at the time, Masisi, was actually very understanding about it, but we created a political headache for him. This is his neighbor. He doesn’t have sanctions on Zimbabwe, and he’s now having to figure out how the US delegation for the US-Africa Business Forum can be quarantined from the Zimbabwe leader. That just felt over the top.

The main political driver for the US here was, “We can’t give them the photo op, or the moment that can be read as us being too buddy-buddy”?

That’s it. But this is a forum about increasing US trade investment in Africa. Let’s not get twisted on what we’re trying to do, which is invest in Africa. While there are sanctions on Zimbabwe, there are not sanctions on investing in Zimbabwe: it’s with particular individuals and entities. For the sake of a photo op — at the minimum it was a distraction.

What about another example: You had to make sure President Biden stood far enough away from certain leaders without breaking diplomatic protocol during the US-Africa Leader Summit in 2022? How far away is appropriate?

I don’t know how far away — but I played the game a little bit too. We invited about 50 leaders on the continent. We didn’t invite the President of Zimbabwe and Eritrea, because they’re under sanctions. Usually the photo is organized by — alphabetical, reverse-alphabetical, protocol order — there’s all these different ways, and it’s a Rubik’s cube. You’re like, “I don’t like the way that this looks, try a different one.” Then we would try the different one. “Actually, the line of leaders on the second step is going to end here and we start the third step, so we’re OK.” I played into it too, but I keep thinking to myself, “What was it all for?” Was it as important as all of the stress that we had?

Doesn’t it matter? Let me make the argument that it does. I understand much of diplomacy as these elaborate, stuffy games that you play in order to send very concrete signals. Who stands next to who in a photo op is a sign of legitimacy. There’s a reason that we have this whole elaborate, invented-by-the-French language of diplomacy: to send messages.

That would be the argument: that by virtue of being next to the president, a leader is accruing some legitimacy. But you also have already invited that leader to Washington to attend a three-day summit hosted by the President of the United States. If you wanted to make a political point and say, “Because our relationships are cordial enough that you’re invited but not warm enough that you need to be the next to the president” — it’s not like we told those leaders that.

They’re meant to pick it up from where they got staged in the photo op?

They’re unlikely to pick it up. So it’s a kabuki dance for I don’t know who.

Who’s it for, then? Is it a dance for an American audience?

I think at the heart of it is a fear that someone would see it, get upset, and yell at us. That you would have activists, or the Hill, or legitimate civil society in those countries, express deep frustration with the US for doing that. You’re fighting against a potential future, trying to ward off a scenario that would be uncomfortable.

We have all these different events throughout the three days, and African leader X will speak at this summit event and African leader Y will do this one. Then we shared the schematics with the African diplomatic corps. A couple of diplomats were like, “Where is our leader? How come they don’t have any speaking engagements?” Nine times out of ten, it was because that was a leader we had a challenge with, and we ended up fixing that. But the African ambassadors are right. “You’re going to be inclusive and ask our leader to come here, but you don’t want to give them anything to do the entire three days?” We did fix it, but it was out of that same sense, “Uh oh! Someone’s going to be annoyed at us.” I think that got in the way of doing good policy.

What’s the value of a convening like this? In a past job, I used to help run a retreat that I really loved. It was a fantastic event, mostly because of all the serendipity that happened. You put a bunch of people together and they formed companies and built lifelong relationships that you didn’t plan exactly in advance. You choreographed the whole event, but you couldn’t foresee specific outcomes.

An event like this, where you’re convening all 50 African leaders, I assume there’s some of that. But do you have very concrete goals as well? How does the National Security Council (NSC) think of an event like this? What constitutes success?

There’s a couple of metrics that we use, like:

How many private sector deals were announced?

What kind of initiatives did we launch?

How is it received by Americans, by our African partners, and, quite frankly, by our adversaries?

We’ve only done two African summits, in 2014 and in 2022. China does one every three years. Japan does one every three years. Most allies and adversaries do it much more frequently. But what’s special — particularly when we do it in Washington — is for three days, this town is about Africa. You hear a traffic report: “Because of the Africa Leaders Summit, it’s going to be more difficult to go down Pennsylvania.” It’s both symbolic and literal that Africa becomes the focus of Washington DC.

The Secretary of Transportation’s like, “Where’s my Africa meeting?”

All the think tanks that may spend very little time on Africa are like, “We’ve got to have a big Africa thing. Let’s make sure we host this African leader here during the summit.”

All the private sector companies are like, “You’re having a summit? Let’s hold back our big announcement, so we can announce it at the summit.” Or, “Is there a leader or a country that we’ve been on the fence about, that maybe we can have an initial engagement, that we can start talking about an MOU.”

The Trump administration for a minute talked about doing it in New York, and I thought that was a disaster. You wouldn’t get the focus, time, and attention to do it in New York on the sidelines of the UN General Assembly. You wouldn’t have the Secretary of Commerce or Housing and Urban Development coming up. There’d be too much distraction. Doing it in DC is important. One day it’d be great to do it on the African continent. But for a town that doesn’t spend a lot of time thinking about Africa, you force the issue with those summits.

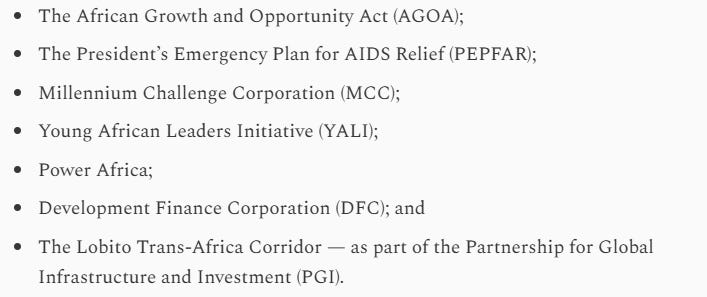

The metric that you mentioned about how many initiatives are announced — you had a piece about the more than 60 US government-launched initiatives on Africa, often presidentially-backed, since the early ‘90s. You’ve got your shortlist of the successful ones: it’s a little bit more than a handful. The vast majority flame out or don’t last past the administration. I have a sense that the number of deals and new government initiatives announced at something like this is vaporware. Am I right in taking that cue from you?

It can be. There’s a good and a bad way to do initiatives. The best way to do an initiative — and I would put PEPFAR, the President’s Emergency Plan for AIDS Relief as a great example [Statecraft previously spoke to Mark Dybul about why PEPFAR worked], or Power Africa under Obama — where the administration team sat down and thought through what they were going to do, without a hook. It was: “This is important and we’re going to take the time. We’re going to build stakeholder buy-in, launch it, and work with Congress.” Those stand the test of time. That’s the best way to do it.

The bad way to do it is, “We need a deliverable because the president’s going somewhere. Can you guys come up with something?” You’re robbing Peter to pay Paul. The reality is somewhere in the middle, which is that when you have a president like President George W. Bush — who’s going to support you even without a summit — you have an ability to do some big things. When you have presidents that are going to spend less time on Africa, you need those summits or initiatives to break through the bureaucracy.

What I did with some of them — most of them didn’t survive, in part because the Trump administration cleaned the decks a little bit — is instead of being, “Here’s the big initiative that’s going to define our Africa policy that we’re using the trip or the summit to do,” I had the view, “Let’s use the summit to get a crack in the door of something cool and interesting.” With 21PAS, we had this idea for how we do positive conditionality for security assistance. “Let’s call them a pilot. We can birth them with the summit, and then let’s spend the next months and years to see if they’re a real thing.” If they are, you have the momentum to make them long-lasting and core to what we do.

That was my middle road. I needed the summit to have leverage, but I didn’t want to over-promise, and so I actually put in three or four initiatives. None of them would get all of the attention and die under the weight of the attention. They were creative and different, and they needed some nurturing and bureaucratic buy-in to see if they could leave the home and fly away.

When you reflect on that tactic of throwing a bunch of small initiatives in and trying to see which ones take root, would you do that again?

I would do a little of that again. I would carve out more space to think about the big project. I really wanted to do something in urbanization. I hid it in the strategy and I just couldn’t find the time to do it, and I really do regret that. On the initiatives, I learned a little bit from that process. On ADAPT: I had a lot of stakeholder buy-in. I had USAID and State working on it, and a lot of test cases with the coups to work them through. I think it would’ve probably lived on. As the end of the Biden administration was upon us, the team spent all the money because they thought it wouldn’t live in the Trump administration. But the concept was solid, and we were seeing people think about, “How do we use this?” That was a positive one.

The positive conditionality, which we called the 21st Century Partnership for African Security, 21PAS: we shoved it down DOD’s throat. We literally had Jake Sullivan call Secretary Austin, and they found money for it. DOD hated the idea and did not want to do it. They fought us tooth and nail, and there was no other agency or department that had any skin on it, so DOD were able to say, “We’re not going to do it. We’re just going to appropriate the money as we always have.” It was really unfortunate.

So I would probably do some of the same things, but I would think even more deeply about the construction, the stakeholders, how it could grow over time, and make sure that even if we had this spark from a summit or a trip, that I had enough momentum and buy-in to actually build it over time.

We’ve talked a lot about the US government’s interest in supporting democracy in Africa, and this was a big theme with the Biden administration. That sat next to more realist moves, like an embrace of Angola for geostrategic reasons. Angola is not a thriving democracy, but it matters for critical minerals. How did you guys think about that balance internally?

They don’t have to be in tension: our realist geopolitical goals vs. a values agenda. But sometimes they are. There were a number of important things that were happening in Angola, not just geopolitical. The leader who had been in power since 1979, left power in 2017; peacefully handed it over to his successor. His successor was looking at economic reforms, being more active in the region, and we were making all these investments in the rail. It continues to have challenges with growing its democracy, but it was making important steps.

We have to take these countries in full. We have to think about the progress that they’re making on democracy and values, as well as the geopolitics — not letting one be hostage to the other. Too often, we were letting one particular factor — it could be democracy, but if you look at today, critical minerals is the most important factor. The way that I wanted us to think about the continent is, think about each of these countries having multiple points of value to us. This country is doing important work on hydro energy, or it’s leading the charge on climate change, or it’s been a remarkable partner on COVID, or it’s a democracy, or it’s a counter-terrorism partner. I wanted us to inject more complexity in these relationships. If we’re going to meet with a leader about China: maybe we are in alignment on some of the issues around China; we could also talk about some of the things that we disagree with. I would tell a couple countries that we have one of the most mature relationships on the continent because we fought hard about a bunch of things and cooperated so well on a bunch of others.

What are those countries?

One is South Africa. We were having difficult conversations with South Africa about Ukraine, and whether or not it’s non-aligned.

Because South Africa is aligned with the Russians?

South Africa, during Russia’s war with Ukraine, took a much more neutral position. Sometimes they would reiterate Russian talking points. They wouldn’t vote with us in the [UN] General Assembly. At one point they had a dueling General Assembly resolution. They wanted to negotiate, which is not what we wanted to do. We had a line, “Nothing about Ukraine without Ukraine.” They did naval exercises with China and Russia.

But they’re also a vibrant democracy. The ruling party lost its majority in 2024. President Biden and President Ramaphosa had productive conversations, where they talked about their differences of opinion, and particularly on the Russian war in Ukraine. We didn’t necessarily see eye-to-eye, but we were able to narrow those differences. Jake Sullivan had a productive relationship with his counterpart, Sydney Mufamadi, where they would talk on the phone. He invited Sydney to join him at a couple of these meetings of national security advisors in Malta.

South Africa’s in the news right now with President Trump in this false allegation of white genocide. Certainly there are real problems with corruption and violence in South Africa, but we took South Africa as it is, and I thought that was a more mature relationship than the sort of one-note approach that we can have in other places.

Was that allegation of white genocide, of the killing of farmers, one of the things that you talked through with the South Africans?

There is no white genocide. There are more black South Africans killed in South Africa than white South Africans. It was part of the bilateral conversation about violence, police training. It was not brought to the level that it was under Trump I or Trump II. But our embassy did engage on a bunch of law enforcement and security issues as much as they could. It is a big issue for South Africans. One of the many reasons why the African National Congress lost its majority is because there is rampant crime in lots of parts of South Africa. It’s a concern to all of its citizens.

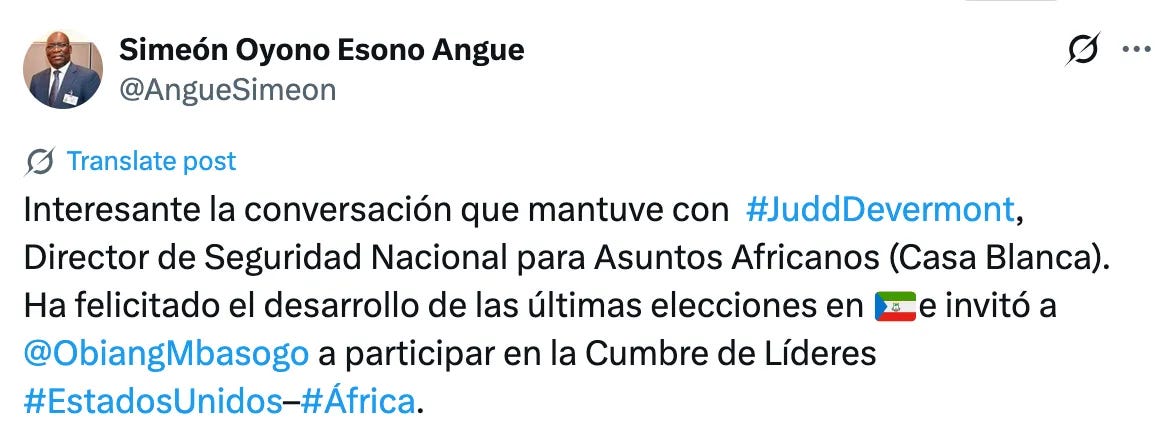

Let me ask you about another case of engagement you’ve written about, with Equatorial Guinea. There was a presidential vote that the Biden admin publicly condemned. The admin said there were, “Credible allegations of fraud, intimidation, and coercion.”

Then a few days later, you personally had to call the Equatorial Guinean foreign minister to congratulate the president and invite him to this summit at the White House, despite what the US had publicly affirmed. Tell me about that incident.

Secretary Rubio’s decision not to comment on elections was a spur for writing about it. The US government comments on more African elections than any other region in the world. With maybe one or two exceptions in the last four years, we commented on every single election. Some statements were pretty paternalistic, some were pretty vanilla, but almost every single one. That’s not true for Europe, US diplomats almost never comment on European elections, or Latin America — they’re actually the most vociferous of comments, on Maduro’s elections in Venezuela — or in Asia-Pacific.

Because we had traveled to Equatorial Guinea, Jon Finer, and then myself and the Assistant Secretary Molly Phee, and then they had this election, it was problematic. There was a statement that was pretty punchy, and it was just before the Africa Leader Summit. The Equatorial Guineans called up and said, “Why are we coming to Washington if this is what you think about our election?” That was not the outcome that we wanted. We have a whole bunch of issues that we wanted to engage with them about. We were on the record that we thought the re-election was problematic, but we were saying, “We don’t recognize that President Obiang had won his election.” So I called up the foreign minister and said, “We look forward to working with President Obiang and his next term and that smoothed it over.” He tweeted about it.

I remember it was 6 AM and I’m outside of my house on the phone, chatting with him about this election. This gets to this question about balance. We should be able to talk about democracy and human rights. I just think it’s one of the many things that we need to think about in our relationship — and figure out how we do all of these things in a way that not all of them are canceled out.

Why can’t we walk and chew gum? We should be able to do that in Africa, because we do it everywhere else.

Let me tie this back to the discussion happening among Democrats about the legacy of the Biden admin. One of the big regrets I hear is, “We tried to walk and chew gum at the same time, and it turns out that we couldn’t.” You see this in the everything-bagel critique of domestic programs.

Isn’t there a grain of truth to this critique in foreign policy — that you have to prioritize? That might mean making the decision Secretary Rubio has made, of not commenting on elections, so that you have firepower for other issues that you care about.

I take it a different way: it’s not really about the Biden administration. If we are going to behave in a way, in other parts of the world, that allows space to be critical, to promote trade and investment, and to talk about global issues, why shouldn’t we be doing that in Africa? The challenge is that because Africa is given so little space, both generalists and specialists want to narrow the way we talk about Africa to very specific issues, and let those issues be the ones that wag the dog.

Those issues typically being democracy promotion?

Not really. It depends on the country, but in the post-9/11 era, it was about counter-terrorism. Then starting in the Trump administration and for the Biden administration, a lot of it boiled down to China. Then in this administration, I’m not sure, is it migration and critical minerals in Africa? Those are the issues.

Those are such narrow sets of issues. What we need to be doing is talking about trade-offs and calibration. We should be talking about democracy. When we’re talking to governments that have had military transitions, we should be talking about, “How do we get back to civilian rule?” because Africans, more than any other region, believe in democracy. That’s what polling suggests, that they have the highest percentage of belief in democracy. But they also believe that it is not delivering for them. It’s in high demand, but the supply of it has been pretty low.

So what do we do to get back to democratic rule? What do we do to work with African leaders? Democratic rule has dividends, but we still need to talk about the extremist threat, issues like critical minerals, and the shape of the global order that we are moving into. We should be able to do all that. We have to get off our high horse sometimes, and not let ourselves be captured by single issues. [NB: I’m not sure Judd is right that Africans believe in democracy more than others. See page 23 of this Pew Research study, on attitudes to representative democracy. The African countries included score substantially lower than the Western European countries.]

Let me ask you about the tools that we use to do diplomacy in Africa. A State Department ambassador is the standard way that we interface with other countries, but sometimes a president will appoint a special envoy. You worked with three Horn of Africa envoys, covering Somalia, Eritrea, Ethiopia, and Sudan. Based on that experience, you said we need to reconsider the whole approach to envoys.

What’s wrong with envoys?

The reason why we often do envoys in Africa is because we’re quite short-staffed. Most of our embassies aren’t fully staffed up. With 49 countries as a responsibility, and sometimes multiple crises at the same time, sometimes those crises sort of spill over geographic or bureaucratic boundaries, an envoy ends up being a fix to a problem at the State Department or a problem in the broader national security apparatus.

The envoy is a solution to an American internal problem first: it’s not necessarily the right tool for that job over there, it’s that we need to fix some bureaucratic tangle over here, and the envoy cuts through that?

Exactly. The envoy helps with staffing issues, bureaucratic seams, and focus. Now there’s another thing that happens often with envoys: sometimes it’s virtue signaling too. You’re saying, “This issue is so important that we’ve named an envoy. The President has picked Joe Smith to deal with this problem, hence, we’re on it.” My view, which has been refined having worked with lots of envoys, is that we should be very clear about what we’re trying to solve for. Particularly in places where the issue is bigger than one embassy, or maybe is so challenging and difficult that it would subsume all the time of the assistant secretary and deputy assistant secretaries; then it’s really useful to have someone. Or it’s an issue that is both about Africa and the Middle East.

A great example is negotiations. Sometimes we have an envoy to deal with a negotiation between several countries, and that’s going to be 100% of your time.

I was going to mention Steve Witkoff in the Trump admin, who has been a pretty successful envoy in terms of being empowered to go do a bunch of things, and that’s a primarily negotiating role.

It’s primarily negotiating. But in some respects, Witkoff is running into the same problem of a regular assistant secretary: I think he’s got too many of them to do.

It is a huge brief.

It’s an insane brief. So the problem with our envoys — we don’t staff them up very well either. We didn’t have the staffing to deal with the problem. We’ve named an envoy and that envoy has only one, two, or three people working for him or her. So they don’t have the power to deal with it themselves, to process all the paper, to do the thinking. They sometimes sit outside of the bureaucracy, so they can’t tap into the rest of the country team or the folks back in Washington.

I don’t think envoys are a bad thing, but you have to understand what they’re trying to do. You want to make sure they’re not trying to solve everything, which was one of our problems with our Horn of Africa envoy: they’re trying to do Somalia, Sudan, Ethiopia, Eritrea — with three people. That’s insane. You need a lot of Witkoffs for that. Then making sure that they’re staffed successfully so they can do the work — and thinking about, “What’s their exit strategy?” as well.

You say the White House and the State Department should build a team, agree on what the job is and who’s going to do it, and pick the right person for the gig. You describe that coordination as “fairly obvious, but crucial.” It does sound obvious and crucial. Why is it so hard to get right?

The dirty secret is sometimes envoys are appointed because there’s a view that the current team isn’t getting the job done. That’s not a negative about the current team, it’s just that the issue is beyond them, it’s too immense. You need someone who’s going to run point on this. So sometimes there’s tension by virtue of having an envoy, because it can suggest…

The envoy shows that you don’t necessarily trust the team.

Not necessarily you don’t trust them, but you’re taking a portfolio away from the current bureaucracy and that’s really sensitive. So ideally you all agree that this would be a force multiplier for everyone, and it’s not a fix for something that we seem to not be able to solve in our current arrangement. Then you have to find the individual with the personality that’s going to be effective, not just the resume. Sometimes there’s a lot more about resumes: “This person was a diplomat, he worked at the UN; this person has Middle East experience.” I’m a big fan of one of our envoys, Mike Hammer, who’s just a really smart people-person. He came to Africa late, he was our ambassador to [the Democratic Republic of] Congo. Then we asked him to do this and he hit the ground running. He’s very good at relationships, very dogged. He ended up being the right person, and knew how to work well with the bureaucracy, which was also important.

Say more about the personal qualities of an excellent envoy. What personality types do a decent job?

It depends on the challenge that you’re trying to solve. Envoys that are doing negotiations, I think you really want people-persons. I’ll give you an example from the Obama administration: we had two envoys for the Great Lakes. We had Tom Perriello, who ended up being our envoy for Sudan. He is a lawyer by background, he did serve one term in Congress. Prior to Tom, we had Russ Feingold: longtime Africanist, long time in the Senate. I would watch Feingold engage with African leaders and he built relationships and then stuck the démarche [a formal diplomatic solicitation] somewhere in there.

Politicians are actually better than diplomats. An extension of that is, can you work with the bureaucracy? Make all the bureaucracy feel you’re not taking away something for them? Not that you’re operating outside of them, but you’re doing the work, keeping them informed, being inclusive, and it’s to everyone’s advantage that you succeed.

Let’s say that tomorrow, by some twist of fate, I’m named as an envoy to solve a thorny African issue. I don’t have deep expertise in the region. How do I keep the bureaucracy on my side? What are my first steps?

You spend a lot of time with the staff: getting to know them as people, asking for their expertise and feedback, and finding opportunities to bring them with you. In your conversations with foreign leaders, you’re referencing other senior leaders in the government, and how, “We’ve all worked together on this approach.” You’re not only back-briefing your peers back in Washington, but even setting up calls so they’re involved in the conversation. You’re setting up side meetings for strategy, sharing what you’re learning and asking for their opinion.

It’s a lot of ego stroking.

It’s a lot of care and feeding. Government is full of people. I spent so much time thinking about, “How do I make people believe, feel, understand that I may not do what they say, or what they recommend, but I want to hear their recommendations and I want to hear their input, and I want to be cordial about it?” I don’t think I got that right 100% of the time. Sometimes I think maybe I should have done less of it. But you want people to believe that this is a one-team, one-mission effort — that it’s only because all of us together are in it, sharing expertise and leveraging relationships, that we can move forward, even if one is the one with the ball.

Where is the line on bringing people in? You’ve gone to meetings where there’s a massive American delegation — five or six pretty senior people — to engage with one foreign counterpart. That seems suboptimal.

This was a meeting we had in New York with a foreign minister, and it just seemed like all of us were there. The value is maybe showing this is important, or that we were all hearing the same things, but it probably wasn’t a good use of our time. I don’t know if it was that instrumental in moving the ball forward.

Is the National Security Council (NSC) neutered today? There were lots of stories about how it was one of the most important policy organs of the Biden administration — the nerve center of the White House. What’s your read on it right now?

One of the things that I’m most concerned about is that, for the first time, the Africa Directorate at the National Security Council has been folded into the Middle East Directorate. So there are two people who do sub-Saharan Africa, and they’re part of the larger Middle East team. That really concerns me, because it’s challenging to work 49 accounts. Some you work more than others. But to have responsibility for a very large continent and your boss — in a team of five or six, I don’t know — is also responsible for the Middle East: that’s a challenge. I don’t know the current senior director; I wish him the best. I do think that it’s hard, if you have a couple of slots for a phone call or a meeting with the president, and now you have to pick between Middle East and African countries. That’s hard, if you’re not someone who’s invested in Africa. You’ve only got a certain amount of meetings you can host in a day. My fear is that it relegates Africa even further down the pecking order.

I don’t have a strong view on how to organize the different functions. But if I was steelmanning the administration, I’d say something like this:

In recent administrations, the State Department has often been sidelined by the National Security Council. We’ve had past guests on Statecraft say it’s bad that this whole State Department apparatus doesn’t make some major diplomatic calls. The National Security Council is tiny compared to State, and it’s often the first institution to talk to the President about the Middle East, or Africa, or what have you. Secretary Rubio is clearly a trusted member of this administration, and he’s Secretary of State. Maybe that’s good for Africa.

What would you make of that rhetorical approach?

My experience is not that the NSC was the most powerful player on Africa in the Biden administration. I’ve seen lots of different administrations on Africa; some where that’s clearly the case — the NSC is the most powerful.

Which administration would that be?

In different moments, the NSC was more powerful under President Obama. Under Presidents W. Bush and Clinton, you had the senior director [at the NSC] and the assistant secretary [at State] in lockstep about what they were doing. In the Bush administration, it was almost a division of labor: I’m going to take the lead on some of these countries and issues, and you’ll take the lead on others.

Why that’s important for Africa is that it allows you to “crowd in,” to put pressure on both systems. You’re moving up to the Secretary of State and to the National Security Advisor: they’re hearing the same policy recommendations. When they get together, they’re much more comfortable making a big decision. I had a good relationship with my counterpart. But I do think that under Bush and Clinton, the alignment between the two was closer than I have ever experienced or read about. It allowed for a very powerful catalytic effect.

The NSC is like the emperor with no clothes. It’s only as powerful as people want to believe in it. If they don’t think that the senior director is speaking for the president, all they’re doing is calling meetings.

You always knew if you were doing well depending on who came to your meetings. When I was a director under President Obama, I was constantly looking, “Are you pushing it down from the deputy assistant secretary, to the office director, to the deputy director, to the desk officer? If you keep pushing it down, you don’t think this meeting is very consequential.”

What [makes] the NSC important is giving a space for all the departments and agencies to come together. All of them have their own equities. They all have different tools and goals and you need someone to adjudicate that. Yes, the NSC can get over-dominant and push people around. But the best NSCs are ones where all the agencies believe that they’re going to get equal hearing. That we’re going to make a decision that is going to move us all forward. Not that we’re just getting told what to do and then we’re going to do it poorly, or at least “weapon of the weak”-resistant.

That’s a good reference. James C. Scott keeps coming up on Statecraft. We’re going to have to do a Scott special.

What is the risk, exactly, of cutting the NSC down to size? Of saying, “The NSC has no clothes, the President trusts other organs and voices; we’re slashing NSC headcount.”

The concrete problem is that the only space then for you to adjudicate or talk about Africa is at the cabinet level. Otherwise it’s all within Rubio’s purview. DOD has an important role, and has really important assets and equities. Same for Treasury, when it comes to the International Monetary Fund or the World Bank. Or Commerce. Where is the place in which they go? They are going to disagree with State. That’s not a bad thing, that’s part of the process. If the only time when the heads of agencies and departments are meeting are at the cabinet level, or even at a principals level, you don’t have enough of the rumination, the back and forth, the kicking of the tires, the hardening of positions that you need for a good decision.

I’ll give you one example. Sometimes the State Department would push back, “Why are we having this meeting? We’ve already made a decision, we’re going forward.” Sometimes I would say, “It’s important that the rest of the US government understands what you’re trying to do.” That’s if I was being nice. Other times, I would think to myself, “By coming to our meeting and writing talking points for yourself, getting your staff, and coordinating, your plan is going to be sharper, more refined, and more articulate.” It’s not just performance art so that everyone is included. It’s also about getting the best version of an idea on a table — because of this action-forcing event — kicking it around in that meeting, coming back to it, and moving it up further. At its best, the NSC provides a space for debate, refinement, negotiation, and a hearing of all the different things that have to come into place for us to have a good policy.

This is why we created it in ‘47. If you let State do its thing and DOD do its thing, they often go in different directions, particularly in Africa. Counter-terrorism and security partnerships get prioritized over some diplomatic issues where you need a vote somewhere. You’ve got to coordinate somehow, and you can’t be doing it at a three hour cabinet-level meeting on camera.

When you were at the National Security Council, you would get a lot of intelligence analysis. You didn’t always find the analysis on the big crisis of the week helpful. I want to hear why not.

When you’re an intelligence analyst, you’re consuming and absorbing different streams of reporting: from the embassy, from all the clandestine avenues that one has. But you’re also not exposed to a lot of the email traffic that is happening. You’re maybe not aware of conversations that people are having, but haven’t written up and put into the system in a formal way. The crisis du jour moves fast.

You’re telling me that the spooks are not listening in on NSC calls?

I don’t think people have broken that law yet.

They’re at a disadvantage by giving oftentimes the tactical: “Here’s what’s happening.” I understand the reasons why you want to do that. But I found that the Intelligence Community (IC) — on the crisis du jour — is much better with standback pieces that we can debate on. “It’s been six months into the conflict. We’re at a stalemate. These are the key factors shaping the stalemate. Until one of these moves, we’re unlikely to be right for negotiations.” Or, “We are probably on the precipice of more conflict, or the opportunity for an adversary to come in and exploit this dynamic.” Those stepback pieces are pretty good. But the more tactical pieces, in the throes of a conflict, one or two pieces may shed light on something, but we’re moving pretty fast.

What I appreciated is, “Tell me what’s happening in some of the smaller countries that I’m just not spending a lot of time in.” Maybe I should be worried about a development there. Maybe there’s an opportunity that we can seize. When there’s a crisis taking all my energy, that’s less for other developments elsewhere.

I spent 16 years in the intelligence community. I understand why the IC wants to be in the room, and have something to say in the biggest crises. But that is sometimes very costly to having insights in other parts: to help us have strategic depth, be aware of discontinuities, and help us with strategic surprise.

How much of your work at the National Security Council was reactive and how much was proactive? Was there any room to wake up and say, “This is the priority of the president. I wonder how I can advance it today?”

It was probably 70-80% reactive. The initiatives actually helped us focus on other things. We made a commitment to do the initiative and that gave me some time. I probably thought about this too late — I always had this board in my office of the big things that I wanted to accomplish, and I would look at it and raise them with my team. But in my last month or so, every day or two, I’d put the board in the main room and go through them. That was much more powerful. To have that checklist in our face all the time. My team was working — not just for me, and those are things that I want to do — because we all wanted to do them. But it really helped focus us: to have that checklist and keep nailing it, as opposed to being pulled into the quagmire of whatever the problem of the day was.

At the NSC, you’re working till nine or ten every day. You get home and you’re still dealing with emails. It’s nonstop. You don’t have enough time to do everything that you want. So it’s a big percentage, but in my last month or so — there was probably a better way to keep everyone focused on some of these other tasks, and then we could have a conversation about, “Did we get the balance right?” I found that to be too little, too late. But that was a useful tool.

I’ve been struck by how many people come out of an administration and then say, “If you wanted to do any forward-looking, proactive planning, you had to do it before you went into the executive branch.” Because by the time you’re in, it’s too late. Dean Ball, who was at the Office of Science and Technology Policy, said something to that effect. I’m hearing some of that from you here.

I agree with it in some part. But also before you get into the administration, you don’t understand the administration’s DNA. Unfortunately, it takes a little time to figure out, who are your advocates? What is the leverage that you have? What is the cadence of the administration? You need to sit a little bit in the space. I was very fortunate because I was brought in exclusively to write the Africa strategy and then I became senior director. I was the guy at the poker table that didn’t play any hands. I just looked at people’s tells.

By the time it was my job, I had already seen what kind of emails are effective with Jake Sullivan. I had seen, “What are the trade-offs I need to make with State to have a positive relationship?” I’m thankful for that. My predecessor had to get working on day one, and figure all that out on the job. I had a little more space to observe. More critical is being able to stop and say — and not just in an offsite way — “Are we doing the things we want to do? If we’re not, how do we change our routine so that they’re not aspirational, they’re part of the agenda.”

As I understand, nothing in the White House has one author, everything gets touched by a million people. But you’re the primary author of President Biden’s 2022 US Strategy Toward Sub-Saharan Africa. Coming out of the admin, you said, “I dislike the way we write and present strategies.” What was so wrong about the process for writing and presenting that strategy?

It’s a little bit unique to be brought in from the outside to write the Africa Strategy, as opposed to the team doing that. But it’s a huge credit to my predecessor and the administration that that’s what they decided to do. The irony was, I had written strategies in the Obama administration, classified and unclassified, and I wasn’t a big fan of them. But this was an opportunity, it was an incredible responsibility, and I had done a lot of thinking about what our approach should be. I had written a document at the Center for Strategic & International Studies, in August 2020, called A New U.S. Policy Framework for the African Century, which had a lot of my ideas. I assumed there was already somewhat of a co-sign on what I wanted to do.

The challenge with strategies is, first of all, we call them, “strategies.” Most of them aren’t even strategies. They’re a series of values and objectives, and framing language, but they’re never about, “If we do X concurrently with Y and then follow that up with Z, we can get to our goal.” Our goal is advancing democracy, and increasing trade and investment. Those are pretty abstract concepts and some of them are not even measurable.

When I came in, I remember having this conversation. I said, “Are we writing a strategy, or is the task to write a public diplomacy tool? Is the task to give directive to the interagency that may have budgetary implications? Is the idea that this will be a platform to launch new initiatives? What is the goal?” Unfortunately, the answer was, “All of the above,” and that is probably not the right answer.

I am really proud of probably the first two or three pages of that strategy. It is a vision about the importance of Africa, and how we have to engage with our partners and treat them as real partners. I also — because I am an amateur historian — really like the text box looking back at 30 years of Africa policy. I continue to believe that we had a policy for the last 30 years that had a lot of benefits for Africans and Americans. But the world and Africa have changed, and we needed to update our approach. So I’m proud that we changed the rhetoric and introduced ideas that even Project 2025 mirrored.

The back half I could have done without. It was four objectives. I really struggled with, “Are they even new?” It’s the same ones I put in, one about climate and the post-pandemic world. Different departments and agencies put their little pet rocks in there. That was the trade-off: between getting a strategy document that said something I believed we needed to say; a North star for our policy. And having something that the agencies could say “On page 13, it says that we are going to do Y.”

If I did it over again, I would just say we’re going to do a vision statement. I do like the idea of engaging publicly about our thoughts. A speech is insufficient. Being quiet on it, which some administrations do, isn’t that useful either. But I wouldn’t throw a whole bunch of objectives into it: I wouldn’t have a Christmas tree. I would be very clear about — “Intellectually, how do we think about this moment in Africa and the way in which we want to engage with our African partners?” — and probably leave it at that.

What’s an example of a pet rock that was left in the strategy document?

There was something from the DOD about how we’re going to invest in African defense industries. Maybe not a bad idea. I don’t think we ever did any of that. The one that I always think about is an Obama administration one. Because Secretary Clinton was interested in clean stoves, you would find the clean stove people adding that to every document they had. Ours wasn’t that bad and I kicked out a bunch of them, but that’s the totemic version.

16 pages is long, but it’s not so long that the clean stoves folks can get their point in.

I don’t know where the clean stoves folks were in the Biden administration.

Our assistant secretary had a great idea. She sent a cable to all of our embassies to provide their input before I even put pen to paper, talk to their African government partners, maybe talk to partners in Europe or the Indo-Pacific about what the strategy should be. I talked to a whole bunch of different think tanks and shared drafts of different versions. I tried to consult and get the best ideas, both because that would make the document stronger, but also I wanted people on the other side to validate it, to say, “This is a good, thoughtful strategy in the right direction.”

You were an intelligence analyst for 16 years. How has the profession changed most since you started your career?

There is more competition for insights than there has ever been before. When I first started as an analyst, what the agency said, particularly on Africa, was pretty singular. You couldn’t have that kind of insight. I’m talking about finished analysis. No one was producing that work in a significant amount that you could shop around. In my lifetime — whether it’s the proliferation of geopolitical risk firms, the ability for people to self-publish on the internet, just social media in general, or the fact that at the NSC, I received raw intelligence reports and all the back and forth with the embassies — the bar became higher for the analysis to say something different and new.

I don’t think that they’ve grappled with that enough. [Intelligence] is not the only piece of information that can be exquisite. Exquisite has a meaning, probably different than I am suggesting here. It often means satellites, secret stuff. But I mean an insight that is sophisticated and refined — that will deliver decision advantage now.

I don’t want to put words in your mouth, but you’re saying that some chunk of what the agency provides is on par with the stuff that you could get from a geopolitical risk firm?

Sometimes. I took the bus off into the agency and I would be on my phone scrolling through Twitter, when Twitter was good, and I was at the 80% solution most of the time. When I was at a think tank and wrote my own papers, I was highly competitive with anything the intelligence community said. I don’t think that’s a bad thing per se. But it does put extra emphasis on not just regurgitating reports: diving deep into history, thinking about context, and drawing on political science to challenge a policymaker.

Sometimes, as a policymaker, I wanted you to just tell me, “This thing is about to happen.” But the best pieces were the pieces that challenged me to think differently about the way I was going at a problem. I think you realize that you need to do that when you see that you don’t have a monopoly on insights anymore.

On this podcast, I’ve heard a lot about the US versus China on the continent of Africa. Things that they’ve done well, diplomatically, that we haven’t done. I haven’t heard much from folks on this show about where we stand relative to them in intelligence gathering. Do we have any frame of reference for them versus us from an intelligence perspective in Africa?

It’s a great question. There’s no way I can even figure out how to answer that question without getting in trouble.