In the last few decades, few government interventions have been regarded as successes on both sides of the political aisle. Operation Warp Speed, which accelerated the development of COVID vaccines, is one. CHIPS, the Creating Helpful Incentives to Produce Semiconductors Act, is another. It spurred a massive investment boom in semiconductors on American soil. This was led by the CHIPS Program Office (CPO), at the Department of Commerce. The CPO had to decide how to allocate $39 billion of manufacturing incentives — and then negotiate the details with some of the biggest companies in the world.

Today, I’m lucky to have three of the founding members of the CHIPS Program Office team with me:

Mike Schmidt, the inaugural Director,

Todd Fisher, the Chief Investment Officer, and;

Sara Meyers, Chief of Staff and Chief Operating Officer.

Mike, Todd, and Sara have a clear sense of what went right for them, what went wrong, and what they’d do differently the next time. They’re working on a big project for IFP called Factory Settings, in which they describe what they learned.

Thanks to Katerina Barton and Harry Fletcher-Wood for their support on this episode.

For a printable PDF of this interview, click here:

When you entered the CHIPS office, what did you have to work with?

Mike Schmidt: A bill passes, and what you’re talking about is a startup. There’s nothing — no people, no processes, no strategy. I was the first employee of the CHIPS team. I started in September 2022, about a month after the bill passed. On my first day of work, Secretary Gina Raimondo introduced me to Todd Fisher, who would become our Chief Investment Officer. The key imperatives were:

Building a vision: how are you going to measure success?

Building a team: we knew we needed an extraordinary group of people to help us get it done.

Building a program: the nuts and bolts of how it’s going to work.

The early days were characterized by trying to figure those things out.

Sara Myers: To design a program is to design hundreds of processes from scratch. We had a couple of things going for us in the beginning. We had 30 detailees from across the Commerce Department, trying to help us build the thing. We also had the attention of the senior operations and administrative folks around the Commerce Department, who understood that this was coming and that we were going to need to ramp quickly.

Todd Fisher: The Secretary [had a] sense of urgency and a willingness to do unnatural things, including helping to recruit people — that was critical.

Secretary Raimondo helped you recruit talent?

Todd: This was obviously one of the biggest priorities for the Biden administration; one of, if not the, biggest priority for Secretary Raimondo. She viewed her role — and played it exceptionally well — as helping to break through barriers for us and be the lead recruiter. And the way the statute was created allowed us some flexibility in how we designed the program.

Mike: The other thing we had was $780 million of administrative funding. Most people operating in government are hamstrung by budget. We expected to have to live within that budget for 20-30 years in total, and the spending would be more early on as we ramped up and allocated the funds. But in those early days, we knew we had the resources we needed to make it happen.

Sara: I remember interviewing with you and being like, “So what do we have, resources-wise here?” You were like, “Just don’t worry about it.” I was like, “It’s a thing that you always must worry about in my experience. So what are you talking about?” When you said $780 million, I was like, “He’s not right. He doesn’t know what he’s talking about.”

2% of the total money allocated for CHIPS was for your administrative operations, which is not a huge percentage; but it’s more than enough to run an office.

How do you know CHIPS was a success?

Mike: CHIPS was passed because semiconductor manufacturing capacity had declined pretty dramatically over the course of a few decades, from around 40% to around 10%. Semiconductors are foundational to the entire modern world. On the leading edge — the most advanced chips — production declined to zero. Those are the technologies that are most critical for AI, and the technology and geopolitics of the future.

At leading-edge logic, which is a critical aspect of the supply chain, all the production is happening in Taiwan — a geography of intense geopolitical sensitivity. CHIPS is a bipartisan statement saying, “We have to reverse that trend. That is not sustainable from a national security standpoint. We need to onshore production of semiconductors, in particular leading-edge semiconductors.”

In terms of measuring success, one is we got it done: we allocated the funds. It’s very hard to execute in government. In less than two and a half years, we awarded $34 billion, starting from nothing. That stands up to parallels in the private-equity world.

Towards the end of the program, we were meeting with the Secretary weekly to go through the pipeline, deal by deal. She was turning the screws, as she should have, to make sure we were going to get it done — but also offering to help: “What CEO can I call? How can I unlock this to help you guys get it done?” We were walking out of her office one day — we knew we had 15 or 20 deals to close in the next few months. Todd worked at KKR, a renowned private-equity fund. I said, “Todd, how many big deals do you think KKR will close between now and the end of the year?” He was like, “Two or three.”

Todd: I think people don’t understand what it takes to get a significant deal done. In the private-equity world, maybe a firm would get five or six transactions done in a year. But remember, all of the processes are in place: they have lawyers; they know all the terms that need to be agreed. We had to get the whole process out there: the application process, a portal, get applications in, evaluate and negotiate them — and get a final, signed agreement in place. Not to mention hiring 180 people, getting them integrated, and creating a team spirit. All those things are taken for granted. There’s a reason you don’t give $39 billion to a startup, because it’s complicated to get it up and running.

Mike: The other obvious measure of success: awarding funds doesn’t matter unless that’s having the outcome you want. We’ve seen a massive amount of private investment catalyzed in semiconductor manufacturing here in the US: over $600 billion in announced investments. There are five companies in the world that can produce leading-edge chips: TSMC, Samsung, Intel, Micron, and SK Hynix. All five of them are expanding here. There’s no other place in the world that has more than two of those companies.

The scale of each individual investment is extraordinary. TSMC’s investment is the largest foreign direct investment in the history of the country. Now it’s $165 billion, but the $65 billion deal we signed with them was the largest. They’ve announced the full plan to build out their site there, and plans to build out a second site. TSMC is producing leading-edge chips in the United States — the first time for any company in a decade — including the most advanced chips in the world, Nvidia Blackwell chips.

It’s still early innings. This is an initiative that will play out over the course of decades. But where we are in the game, it’s looking pretty good.

Todd: When the CHIPS Act was passed in 2022, the US produced exactly 0% of any leading-edge logic or memory chips — all of which are critical to AI, and to all GPUs that Nvidia manufactures, not to mention iPhones and other infrastructure. We are on target to produce — by the end of this decade — 20% of all leading-edge logic chips in the world, and up to 10% of all leading-edge memory chips by some time in the mid-2030s.

Those massive investments draw very significant investments up and down the supply chain, which creates ecosystems that become self-sustaining, which creates dynamism in the economy. We are not there, but all the announced deals, and what’s being done on the ground now, should get us there in that timeframe.

The bill passes late in 2022; you’re hired in the months following. By 2023, what are you doing day to day?

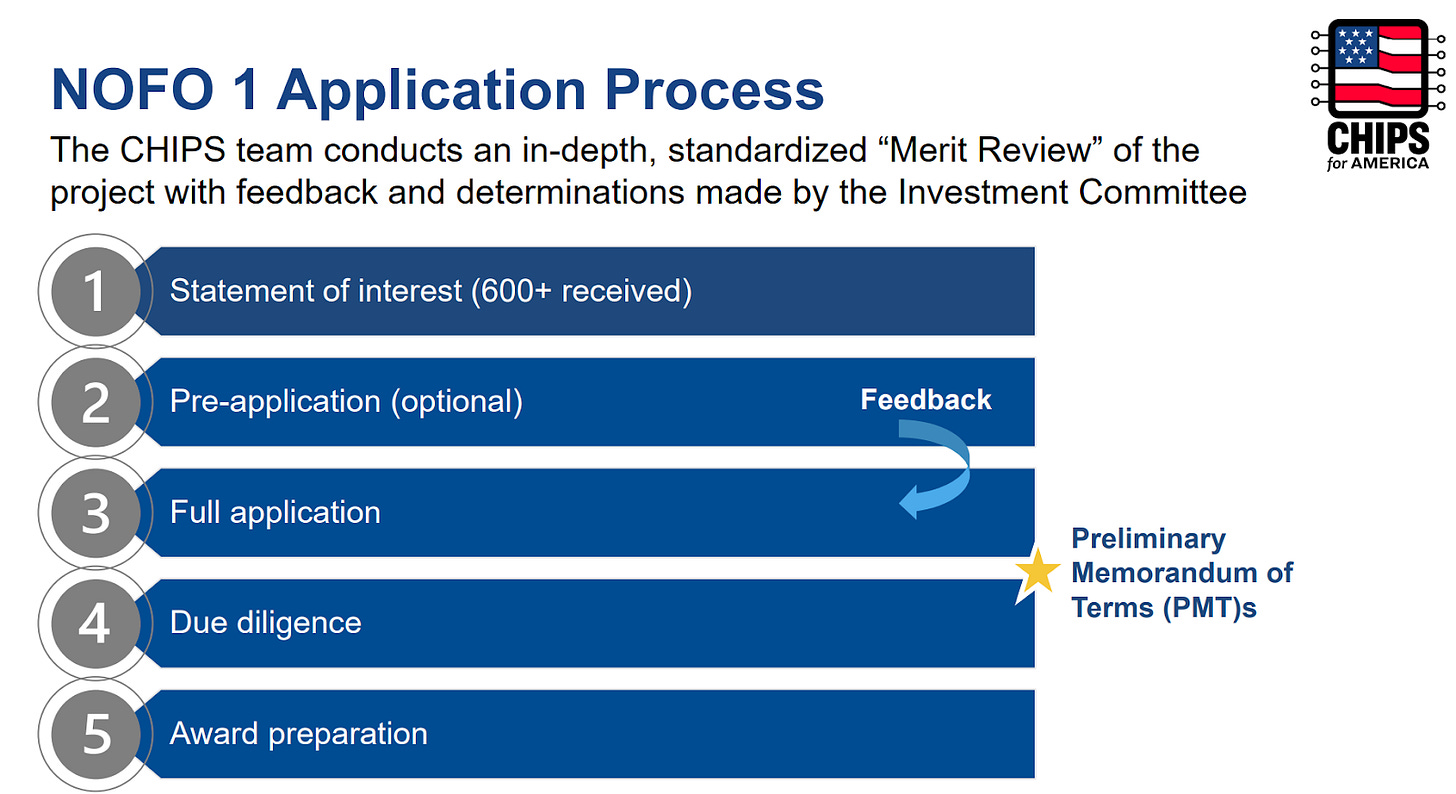

Mike: The Secretary said, on my first day of work — at the White House podium — we were going to put out our Notice of Funding Opportunity (NOFO) in six months. A NOFO is how you describe what the application’s going to look like, how you’re going to evaluate it, how you’re going to get your deals done — “Here’s what we want companies to do.”

So those early days are figuring out, “How is this thing going to work?” We put out our Vision for Success.

Mike: It’s the basic architecture that you then have to fill out. As you’re designing the big picture, you begin to think through the small picture. We were doing a lot of resource planning. Todd, you remember those early meetings with the Secretary?

Todd: “How many people do we need?”

Mike: “Are we going to be ready? When are the applications going to come in?” Trying to project that out. Once the NOFO was out there in February of 2023, we wanted to be ready for contact.

The funny thing was, it took companies longer to apply. There was this weird period over that summer of 2023 where we were waiting. There’s plenty to do in terms of standing up the program and hiring the team. But it wasn’t until late summer or fall of 2023 that we were actively evaluating and negotiating.

That’s because a company like TSMC is going to take its time figuring out how to angle for $7 billion in government incentives?

Todd: We control when we put our funding opportunity out and the rules of the road. We don’t control how fast someone responds. We set the process up so that these leading-edge companies could apply quicker than others, because we thought they were going to be ready to go. I think we got Intel’s last application in September 2023 — six months after we put out the NOFO. You can’t control these things.

Sara: It was a little bit of a blessing, because by the time we hit June, we were at 100 people and we were reasonably ready to rock and roll.

The development of the NOFO is the thing you negotiate with the interagency. That first six months — from August to January — there were five official employees, between 0–30 detailees, and negotiations with the interagency about what should be in and out.

Mike: Six months to write a NOFO means three months to write a NOFO and three months of interagency negotiation.

We’ve talked about the interagency a bunch over the last two months on Statecraft — with Judd Devermont, who was on the National Security Council (NSC), and Dean Ball, formerly of the Office of Science and Technology Policy (OSTP). Were you all in the room with folks from this panoply of agencies? What were they pushing you on?

Mike: The White House set up some governance around the interagency that was hugely helpful. There was a CHIPS Coordinator that operated at the deputies level: Ronnie Chatterji [who spoke to Statecraft a year ago] and then Ryan Harper. The Coordinator was reporting into all the relevant principals: the Chief of Staff, the National Economic Council, NSC, and OSTP. We had a node of coordination.

Still, the interagency is a lot. You write a NOFO and send it to the Office of Information and Regulatory Affairs. Your NOFO goes out, not only to every agency with a potential interest, but to every White House office that interacts with those agencies. For every subject area — national security, cyber, environmental — you’ll have multiple sources of input, which might not always align.

What you’re sending around to the interagency — is this a Word doc that everyone’s adding their comments on?

Sara: That’s right. Then you’re responsible for responding to everything.

Mike: NASA wanted us to make clear that we’d fund semiconductor investments both on Earth and in space. We were able to say, “The statute requires it to be in America, which is Earth.” The way to move quickly is to accept comments. But if you accept every comment, you lose the thread on what you’re trying to achieve.

Sara: We didn’t have to write a NOFO. The NOFO required us to go through the interagency process in that more fulsome and traditional way. It was a choice that offered us structure, and protection from critiques that we were doing it in isolation. But it added time to the work.

Todd: Early on, we faced a bunch of criticism about “Everything-Bagel Liberalism.” Part of that is trying to find the balance between moving quickly and resolving interagency issues — and getting everything perfect. We had designed this in a way that allowed us to have a much more holistic approach [to evaluating applications]. We felt we could accept some of the comments from a bunch of the interagencies, move fast, and still have some flexibility as we made decisions.

For the first six months, it was all about getting ourselves up and running, and putting rules of the road out for those who were going to apply. The next six months was about starting to engage out in the world with potential applicants, and pushing them on what we would like to see, until we finally get those applications in, and start to evaluate them.

Phase three is the Preliminary Memorandum of Terms (PMT) stage. “Now we’ve got all these applications, how do we figure out how to enter into agreements on what these deals will look like, on a preliminary basis?” That’s a massive puzzle that you’re trying to put together, and use your $39 billion in an effective way. That was another six or so months.

The final stage is, once you have these PMTs, getting to legally binding agreements. That was a very tough process that got us to, at the end of the Biden administration, this $34 billion of deals.

You brought up the “Everything-Bagel Liberalism” critique…

Mike: Todd brought it up, just to be clear. Thanks, Todd.

This was a phrase that Ezra Klein originally used — the idea that the Biden administration wasn’t picking specific targets and then building programs around them. The CHIPS program was one of his examples. A component of CHIPS that came in for a lot of heat was that companies with large awards had to have a plan for childcare in their site. That’s one example of a broader critique of the Biden administration, and it’s a critique I’m sympathetic to.

I know all three of you have thoughts about that.

Mike: The core thing that the criticism missed was that we had set up an evaluation and negotiation process that was iterative and holistic. Our North Star was economic and national security. We were very clear about what that meant in the Vision for Success. For childcare, the statute required that we asked for a workforce plan.

Congress made you do that.

Mike: I think that’s fully appropriate. Workforce was a hugely important priority. We wanted to see childcare as part of that workforce plan. In terms of programmatic impact, I think we ended up getting some positive commitments from applicants. But it was not a sticking point.

It didn’t slow down the process?

Mike: Definitely not childcare. I spent hundreds of hours negotiating with these companies. I probably spent 30 minutes talking about childcare.

We thought that childcare, and workforce in general, was an important part of meeting our overall goals. Where we ran into problems is where there’s an institutional actor outside of the Department of Commerce that controls your fate and that may have different incentives. Those can be real choke points.

Todd: If you’re doing industrial policy like this, where the main thing is national security, that needs to be the priority. It is hard to stop other priorities from inundating you when there’s a lot of money around. We didn’t get it perfectly right. If we’re successful, CHIPS will drive jobs, but in my mind, it’s not a jobs program.

Micron, when this was all going about, was building a big childcare facility in Boise, because they recognized that in order to get people to come and work for them, they needed to provide childcare. If you go to Taiwan or Korea, all of these ecosystems have massive childcare facilities, because it is all about talent. If you talk to the companies about the biggest risk to this program, workforce is going to be in the top one or two.

I want to hear where you made hard calls in the interagency to keep stuff off the menu.

Mike: We had a fair amount of friction with applicants on requirements related to national security: cybersecurity, operational security, and the use of Chinese equipment. We were making some discretionary calls around what expectations we wanted to set, and they required a fair amount of negotiation. This is all on top of the national security requirements of the CHIPS Act, which constrained, for example, investment in manufacturing facilities in China. There were real trade-offs and healthy tension within our teams.

Sara: Something that we rejected out of the interagency process: we were pushed pretty hard to say what recipients were going to have to report to us upfront, as is normally required in a NOFO. We were able to say, “We are not ready for that. We have so much more to figure out here.” It ended up taking us two years to figure out exactly what that reporting was going to look like — how to make it not overly burdensome, and give us the data that we needed.

Mike: I remember you calling me and explaining, “With the Paperwork Reduction Act (PRA), we’re going to have to publish our reporting requirements for companies in the next few weeks.” My reaction was, “No, we’re not,” because we knew these were commercial things: we were going to have to negotiate it. Whatever we were going to have to do — emergency PRA exemptions, whatever pain we were going to have to take with the Office of Management and Budget — was necessary.

Why is that such a big deal?

Sara: Designing what people are going to have to report is always a big deal in government. There’s an inherent tension between getting everything the program might usefully use and anything that a recipient might want to do — it’s a huge burden. As somebody who’s been a recipient of federal dollars, all that reporting stuff might make sense to the federal agency. It makes zero sense to the people who have to do the reporting.

PRA makes it so that you have to pretend you can understand the trade-offs between the burden and the benefit in advance. [Statecraft has covered the Paperwork Reduction Act’s failings.] In this context, it’s even more complicated, because there are different deals, actors, and operating models on their side. Not to mention that we have to build the reporting system to ingest all this information.

Todd: This is not an interagency thing, but there were lots of internal debates about stock buybacks. These were a big thing for certain parties on the left.

People opposed companies buying back their own stock if they received CHIPS funds.

Todd: Obviously none of our money could be used to do stock buybacks. That was in the statute. The question was, “Can companies do stock buybacks at all?” You’re trying to incent the private sector. 5%-15% of the total money was coming from our office. The majority was being put in by these companies — who have to go out and talk to investors every single day. What you’re focused on is getting these companies to make significant investments in the US. But if there’s money after that, allowing them to give some back to shareholders is not crazy. Trying to focus on, “What are we trying to do?” and then allow companies to engage with the investors that they need — it was very complicated.

Let’s talk about Davis-Bacon, a law that requires federally-funded public works contractors to pay construction labor the local prevailing wage. This posed some issues?

Todd: Davis-Bacon was passed in 1931 — the Herbert Hoover administration — in an effort to create local construction worker markets. Many things about it are a bit anachronistic, but we all agree with the intent of trying to pay local construction workers the prevailing wage. The challenge is it had never been applied to something of this magnitude. There were tens of thousands of workers on a site like TSMC’s in Arizona. They come in and out, because they’re different types of contractors.

We weren’t paying for 100% — the companies were paying for a significant amount. We were trying to get people to start their work before they got their award, so we didn’t lose time. That created a retroactive issue: “What happens to all the work that was done before you got an award?” That had never been dealt with at the federal level for Davis-Bacon. That was the challenge that we, the Labor Department, and others were trying to deal with. It’s a whole administrative burden: how do you go back in time, for tens of thousands of workers, with thousands of subcontractors, and figure that out?

Mike: The industry got that it was part of the deal — it was in the statute and manageable. For fabs under construction, our strategy was to say to companies, “You’re building Fab One. We want you to build three fabs, so we’ll fund a little bit of Fab One, and then use that as negotiating leverage to get commitments for Fabs Two and Three.” But taking money on that first fab triggered this retroactivity issue. You need to look back at every contractor who’s done work on that fab and figure out if they were paid Davis-Bacon wages. That requires tracking down potentially 20,000 employees who are no longer on the site. That administrative challenge was very difficult to work through with applicants.

I’m seeing a through line with laws like the National Environmental Policy Act (NEPA), which we’ve talked a lot about on Statecraft, and Davis-Bacon. In these cases, the concrete requirement of the law — paying a little bit extra in wages — is not as burdensome as the process is. Is that right?

Mike: I think there’s probably some similarities. Both NEPA and Davis-Bacon are governed outside of the implementing agency. Davis-Bacon by the Department of Labor, NEPA ultimately ends up in a court, and a judge determines your fate, which is a terrifying thing if you’re trying to execute industrial policy.

In the Davis-Bacon case, you have a high volume of regulations and administrative case law built up over time. It’s mostly in contexts very different from semiconductor manufacturing. It’s a question of, reckoning with the existing body of administrative law in this new context.

Similarly, you’ve seen an increase over time in what NEPA expects, and that’s driven by litigation. Judges can ask for more every time. There’s case law that triggers an expectation that the implementing agency is going to do more for NEPA, and that accumulates.

Back to the CHIPS timeline. We’re in late 2023–spring 2024. You’re starting to try and get these deals done. You’re negotiating with some of the biggest companies on Earth. What’s your strategy?

Todd: PTSD is coming back. I think the most complicated period was trying to get these Preliminary Memorandum of Terms (PMTs). We put preliminary offers on the table starting around Thanksgiving of 2023. Then it took time — between November and April — to negotiate those. We had $70 billion of requests from just the leading-edge firms that were going to get some subset of the $39 billion. The expectations were way too high, so we had a lot of negotiating. You have to figure out how much you’re giving to each of them, you’re negotiating with all of them at the same time, and trying to get that puzzle to come into place.

Leading-edge companies between them asked for something like $75 billion. You ended up giving them ~$25 billion. In the process of negotiation, you cut them down two-thirds?

Todd: That’s correct. And everybody focuses on the big numbers, but there’s also a whole series of, “When are we going to get that money? On what milestones? How much comes early versus later?” They’re the most valuable and sophisticated companies in the world for a reason.

These companies are hard negotiators?

Todd: They’re tough negotiators — and there’s a reason for the CHIPS Act. TSMC has a credible option to do more fabs in Taiwan. Micron has fabs in Singapore, Taiwan, and Japan. They’re making a real choice: “What is the amount of money that will make it positive for us to put all this capital?”

Sara: By the time we got those PMTs on the table, everyone was exhausted. We had done so much process-design work — every single thing from accepting the applications to how the Investment Committee was going to work. If you asked us a year later, I don’t think we realized how much more intense it could have gotten.

You’re sprinting to stand up this thing, and at the end of the sprint, you start negotiating with some of the biggest sharks in the world.

Mike: Some of them were sharks. Maybe not all.

Sara: When you are standing up a program from scratch, you have to design every single process you run. That is a gift: you get to choose and learn from all your prior experiences. And it’s real hard. The minute the process you’re focused on is stable, you’re onto the next thing. We were designing, testing, implementing, and then just repping out processes, from January 2023 through January 2025. We did not stop.

Mike: Our first PMTs were two small deals. We announced BAE, a small defense manufacturer, for $35 million, and Microchip was $162 million. After we announced BAE, it felt like this Herculean thing. We had an all-staff meeting right after, and I said, “Congratulations. We just need to do 1,400 more, and we’ll be done with the program.”

The core governance of our investment process was the Investment Committee. It had to evaluate the economic and national security benefits, sign off on the merit review — but another important function was figuring out the right size of the award. We had created a framework for sizing awards based on the rate of return of the project. The basic idea was, “We need to make this project make sense for you economically — to make your hurdle rate. How much of our money is going to be necessary?” That is as much art as science.

For those early deals, we were spending hours in the Investment Committee, trying to figure out how to make this internal rate of return analysis work. A lot of people on the team were terrified. People on Todd’s team who we were torturing with all our questions were like, “If you’re asking about this for the small deals, how are we going to do the big deals?” But every time we went through something new, we had to build the muscle. If it wasn’t working well, we had to go back, reiterate, and do new process design — to create as much efficiency as possible, while maintaining the standard we had set for ourselves in terms of analytical rigor.

Todd: This was modeled as a world-class investment firm, where the returns were to national and economic security. Me, with an investment background; others on the Investment Committee that come from the semiconductor industry and had deep technical expertise; Mike with his background in government — trying to get everybody around a table to understand what a good investment looked like. When you’re at an organization, you don’t even recognize the norms and processes that are in place. We were putting all that in place.

You came from a professional environment where these are all fundamental norms. You had to rebuild this for a bunch of folks who have no experience in the boardroom?

Todd: The core investment team all had experience there. The goal of any investment decision-making is, “How do you get people with diverse expertise around a table, where everybody’s incented to voice their views, and make good decisions?” That’s what we were trying to embed. We’d hired many people who were working at the world’s greatest investment firms — Blackstone, Goldman Sachs, VC firms. We had a whole group that had semiconductor experience, that were chief technology officers at GlobalFoundries, worked at Intel, or in the industry for 30 years. Mixing that with the relevant expertise in national security, workforce, and environmental was the challenge and, ultimately, the magic.

BAE and Microchip are the two “small” deals you land. Then TSMC is the first big one?

Mike: I think we announced Intel first, TSMC shortly after, and then Samsung and Micron. Those are our big four.

Mike, you and I were talking recently about you flying to Taiwan for the negotiations with TSMC.

Mike: We had signed our preliminary term sheets with the big four. We had negotiations ongoing with a set of smaller, but strategically important deals — companies like Amkor, SK Hynix, Entegris, Texas Instruments, GlobalFoundries, Legacy.

To get these term sheets to a final award, we knew we’d have to negotiate a lot of the details around policy commitments, like workforce and environmental. There was this general sense that the lawyers on both sides were going to figure out the detailed terms. But when we came up with our draft award documents and sent them out to market, the initial reaction was very negative. Not on the policy stuff, but on, “What is the core legal relationship between the United States government and these companies?”

What were these companies upset about?

Mike: It was conditions precedent, representations, warranties, and covenants…

Todd: It’s all about who bears the risk: the US government, or the company?

Mike: “When can we stop funding? When can we call funding back? How much discretion does the government have? When can the government or the company terminate the agreement?” The default in federal programs is, “Give the government a huge amount of discretion.” But that is not something that these companies were used to seeing when dealing with Singapore or Japan. It became something we had to manage very aggressively.

They would say, “We’re nervous. This agreement is going to last for 10-plus years. Who’s going to be at the CHIPS Program Office in 10 years?” They were making decisions on billions of dollars of investment, based on how much money they were getting. They wanted certainty that, “If we hold up our end of the bargain, we’re going to get that money.” It was a very real and fair discussion.

You hadn’t expected to have to do that — you thought this is primarily the lawyers’ job?

Mike: We had hoped that it could be worked out in the legal details. Very quickly, Todd and I had to become personally involved in understanding the structure of the agreement, where the pain points were, and navigating towards a solution. We spent days in a conference room in TSMC headquarters working through these legal details. I remember one of our lawyers explaining to them what the Fly America Act is. I’m sitting there thinking, “What is the Fly America Act?” It’s a cross-cutting statute that says, “If you receive federal dollars, you can’t support travel that isn’t on US airlines.” We’re explaining that to them, and they’re saying, “How can this work?”

You’re kidding? They have to document that when they fly to the US, they’re not flying on foreign flags?

Mike: For the Fly America Act, it ended up being, “If you use our dollars to do it.” It’s just an example of what you’re wading through within our legal construct. We did a week in Taiwan, then the TSMC team came and did a week in DC. Everyone was tired and wanted to be done, and we were grinding through the details. To keep morale up, we worked with Ryan Harper to do bowling at the White House bowling alley with the TSMC group. It was great for the deal and our relationship with them.

But I remember asking their key lawyer, “How does our contract compare to Japan’s contract?” He goes, “We don’t have a contract with Japan. We just submit evidence of our investment, and they give us the money.” That probably undersells the complexity of Japan’s system. But it was such a stark indication of the difference between our system of government and law, and other countries.

Todd: In June 2024, nobody on the team thought we were going to get all these deals done, because it felt like the system was clogged up. Mike and I felt we had to get involved. If we could land TSMC, and say, “The most important company in the semiconductor industry has agreed to this,” we could then move much more rapidly with others. That ended up being true, but it took longer.

Take Intel, for example. We sent the first [draft] PMT on Thanksgiving of 2023. I flew out on the Monday after Thanksgiving to Santa Clara to meet with their CEO to talk about it. We announced the Intel PMT on March 20th — so four months to finalize, negotiate, and get all that in. We thought that once you had these PMTs in place, the next stage would be easier. Lots of things happened post-PMT, including Intel’s August results announcements, where their stock went down by a significant amount — they ultimately fired their CEO. This space between, “You have an announced agreement and everybody’s excited because we think we’re close to the end,” and getting a final agreement in place, was very complicated.

Mike: It required a huge amount of governance within the team, because we had to figure out how to make quick decisions on what the companies were asking for. Sara stood up internal governance committees so that she could resolve issues, or we could escalate them and design together. You might be spending eight hours with a company in an office. You spend three hours negotiating, then maybe you break up for an hour and quickly call the general counsel, or come to a decision internally, and come back in the room and say, “We’re good to go with X. Can you deal with that?” They would often say, “We’re still waiting for legal to get back to us,” or, “Our head of finance is on vacation.” We were feeling so much urgency, and we had created a pretty nimble structure — it was the bureaucracy of the companies that was sometimes holding us up.

What’s the structure that let you move faster?

Sara: We had office hours, and a steering committee to litigate between the teams: what we would be looking for in due diligence, what our terms in that first iteration of the term sheet would be. Once you create some structure and do a couple of reps, you have precedent for some decisions.

Todd: Two times a week we would get together and go through our priorities: where we were, what needed to happen. You need to have a willingness to make decisions quickly, then a structure that says, “What do we have to do this week?” Then later in the week, “What haven’t we done?” Creating the battle rhythm in any organization to make decisions quickly is critical.

Mike: That started with the Secretary. When we got to this phase, it was every Monday morning with her. We would print out our tracker, deal by deal, and talk about where we are.

The other thing is we had a hugely constructive and regular dialogue with the General Counsel of the Commerce Department. She always knew exactly where we were in every deal, what the pain points were. There would be times where we would have a company in the building. If we reached an impasse, we’d call her up and say, “We need you down here at noon. Can you make it work?” She’d come in and negotiate. Maybe the Secretary would stop by, not to negotiate, but to give a little pep talk.

What I’m hearing is that some of the things that were reported as roadblocks, like childcare requirements, weren’t. What slowed you down was that figuring out complicated financial deals takes time. In practice, where did the slowdown happen?

Todd: In the PMT stage, the commercial deal — “How much? Over what time period? What are the milestones?” — took by far the longest period of time. The next [source of delay] is the contract. That’s not specific, like Fly America — it’s typical contract negotiation in almost any large private-sector deal. You’re always trying to find, “Who’s got the risk?” and negotiate that. The government is used to having all the power. But these are big organizations that are trying to find a more reasonable — “Where are you on the fairway?”

Most of the other things that are talked about — workforce or childcare — did not take a lot. For some of the companies, there were specific national security things that we cared about. Those were important, but some took a lot of time. Then there’s the classic things like NEPA and Davis-Bacon, that took a bunch of time, discussion, and our own understanding. But those were one-offs dependent on individual company situations.

Sara: To the extent that there was a niche thing that was holding anything up — we wouldn’t have let it. We would have reorganized ourselves in service of the highest-priority things, if something in the panoply of requirements had threatened to derail the awards.

Mike: I think that gets to the core point, which is: “Where does discretion lie? Are there other institutional actors who can hold you up?” For Davis-Bacon, we did have some real challenges. NEPA, we ended up with a statutory carve-out for most of our projects. We had already posted public Environmental Assessments. There were some clear signals that litigation might be pending, and Congress intervened.

Todd: While it ended up not being that critical, because of Congress intervening, we knew that NEPA was going to be a big challenge. We set ourselves up to be able to serve that. We had an incredible environmental team that was very proactive, we asked for information, and worked with these teams early. NEPA ended up being legislated away — but even if they hadn’t, the way we got ahead of it — there’s probably some lessons there.

Sara: I think that is the core lesson. We can do a lot of complaining about how hard it is. Maybe Congress is going to come to the rescue — and also you’ve got to just get ready to do the work. In a lot of cases, we did a lot of extra work that maybe we didn’t need to, because it was a better use of our time to get to grinding than it would’ve been to fight the thing that was frustrating. That was certainly the case with NEPA. We would have done the work, and done it as well as we possibly could have.

Todd: I had no idea what Davis-Bacon was, and we didn’t realize that that was going to be an issue. We would’ve set ourselves up differently and tried to get ahead of it — we ended up being behind the ball there.

The way that we set up the decision-making process — we keep saying it was holistic, and we had a lot of flexibility. Most grant programs have this scoring mechanism — three people score it, average it out, and let the chips fall where they may. We didn’t have that. We had a much more holistic process, where we were clear that we had these six categories. The first category, national and economic security, was going to get the most importance in any decision-making. But there were no formal scores or anything like that.

While we had a lot of things in our application that said, “We need to see your workforce plan and your childcare plan,” that didn’t mean that there had to be something specific on that. We could make some decisions on, “This is so important to national security that these issues don’t matter as much.” Our judgment, to the Everything-Bagel point, was, we are comfortable letting people give us their childcare, environmental, and workforce plans, because we’re not saying, “And you must do this.” We’re saying, “We’re going to take that into consideration in a holistic way and make determinations.” We had the flexibility to decide what was in the final award documentation.

If one of these big companies that you felt, for national security reasons, we had to strike a deal with, hadn’t made the cut on this metric, you had ways to make sure you could still find a grant?

Mike: They needed to meet a minimum threshold for each of our six categories. But beyond that, we had meaningful discretion. That’s something I thought about while we were designing the process, because if we had done the default — six points for this, eight points for that — the comfort in that is, by getting rid of administrative discretion, you are getting rid of oversight risk.

You’re being fair.

Mike: We’re being exactly fair, we’re doing what we said. Except I had this inverse intuition, which is, if TSMC had ended up not meeting a threshold, for some reason that we didn’t foresee, because this was so complicated and designing evaluations up front is so hard — figuring out how to change the process so that it was above the threshold — that’s not a comfortable position to be in. I ended up with a good relationship with the lead lawyer on this — we would say, “We need to design this process based on how we’re actually going to do it.”

Todd: Typically, there’s not a lot of proactive engagement with the applicants. Most grant programs are set up where — put in your application, maybe we’ll set up one or two conversations — so that everybody’s treated the same way. We wanted to shape what was coming in. We didn’t want to just do the things that the companies wanted to do. We wanted to push them to do different things. We hired a team of people that could engage with these companies in a sophisticated way. There’s a little bit of risk in it, but we could regularly engage, push back, say, “You should do more here, because that would be more powerful from a national security perspective.” If you want to make sure you have zero oversight risk, you would have gone a different direction, but you might also not get as much done.

I think most people think the Inspector General roots out waste, fraud, and abuse; congressional oversight stops you guys from cheating — Todd is rubbing his eyes and Sara is shaking her head. You have this visceral reaction to that claim. [Sara discussed her experience with the IG at length here.]

Sara: I am fully supportive of there being inspectors general (IGs), the Government Accountability Office, and congressional oversight. It comes down to the execution. I have lived through experiences where they get it wrong — it’s so easy to get it wrong. In particular, when we’re conditioned to say, “The way the government’s supposed to operate is fully-documented, fully transparent, fully fair in everything it does.” It means that you have to do all of the things that we had the luxury of being thoughtful about at the outset: write everything down, then do it exactly that way. If you don’t, there’s a million threads to pull on. IGs get congressional appropriation, and they have to deliver work.

They have an incentive to have a big headline. One of the ways in which this has all gotten unhelpful, in the typical government experience, is we have so much fear of oversight. Having a constructive relationship with your overseers is an important thing that lots of programs don’t ever experience or try.

We tried to do that, and it makes all the difference in the world, because then you at least start to level the playing field in terms of the information-asymmetry problem. They don’t know all the context for the program you’re operating. We tried to anticipate, “What are all the places where, in our process design, it’s going to be important that we write down why we made this choice?” We erred on the side of more documentation than we needed.

Mike: There are two pathologies that emerge because of concerns about oversight risk. One is that you design a process to be immune from criticism. Our mantra was, “The biggest risk is that we don’t get this done.” If we’ve successfully implemented the program, and a year and a half from now there’s a negative IG report on the process, I can live with that. That doesn’t mean we’re not going to engage proactively and have documentation, but that is a trade-off I’m willing to take if, a few years from now, fabs are being built and chips are being produced.

The second is a paralysis around risk of bad outcomes. You do one deal that goes poorly, and that ends up driving a narrative about the program, headline risk, and congressional oversight. You want to have all the analytical rigor deal by deal. But we thought as much about risk of omission as risk of commission, and we thought about risk at the portfolio level, not just the deal level.

You had this portfolio of companies, and you weren’t expecting that every single investment would be a massive success?

Todd: Inside government, you always hear about “Solyndra risk” — something goes really sideways. A knee-jerk reaction is, “We don’t want another Solyndra.” I think that is a very wrong way to frame things. If we’re eliminating risk from the portfolio — we’re not doing things that have no risk of failure — then we’re not doing anything that the private market won’t do themselves. We need to take educated bets, and do good underwriting and analysis.

We had this robust debate with Secretary Raimondo about, “We need to make sure the world understands that we’re trying to incent something, and not everything’s going to be successful. But it’s okay if some of our investments don’t go as well as others if we’re accomplishing the ultimate goal.”

In leading-edge logic, we gave awards to all three — Samsung, Intel, and TSMC. What we said up front is, “We need at least two ecosystems in this country to be successful at leading-edge.” The market’s going to sort that out, and hopefully all three will be, but at least we know we’re on target for getting that 20%.

Sara, will you tell me about some of the challenges with the IGs?

Sara: We were wildly successful at hiring very quickly. Our average time to hire was something like 67 days at the end of 2023, after the big surge that we did. The benchmark for the government is 80 days, and I don’t know that agencies have ever actually achieved that. It’s more like 101 days, the last time I looked at the Office of Personnel Management (OPM) Dashboard. We hired more people than we expected to be able to in that first nine-month sprint. The whole time I’m there, I am anticipating when the first call from the IG is going to come. We get the first one, and it’s about hiring, which makes sense.

Hiring’s always a big risk. You could get a bunch of money from Congress, and if you don’t have the people in place to deliver the program, you’re going to be behind. We felt pretty confident going into that. We handed over all the data and answered all their questions. We get the draft report back, and the headline is, “CHIPS succeeded in hiring all the people that they wanted to hire, they exceeded their hiring goals, but they did not develop a comprehensive workforce plan.”

What’s a comprehensive workforce plan?

Sara: I don’t even know — I’ve been in government for a long time. This is a recommendation from OPM that you do this multi-stage planning document, which makes sense in some abstract way.

What did they want you to have developed?

Sara: Literally the number of positions — in government HR language, “What are the functions and capabilities that you need? Why? How many people in each thing and over what time?” I’m sure there’s all kinds of stuff about estimating attrition and whatever to come up with some very formulaic answer for what you should then go hire for.

I have actually never conducted one of these things. I think usually they are for an entire agency. They were applying this standard to us. I’m sure there’s also history with the work that they had already done to look at the National Institute of Standards and Technology and Commerce in the past. They’re bringing some of that baggage to it. But that is the headline, and it takes up two thirds more real estate than the fact that we succeeded.

That you hired ahead of schedule?

Sara: Absolutely absurd. We had hired ahead of schedule, faster than the benchmark, and had a highly efficient process.

Mike: Not to mention, we’d built an unbelievable team. They didn’t even get into that. The mindset that one has, to provide that feedback — there’s such a delta between that process bureaucracy and what it took to build the team.

There were some notions about what the org would look like. I thought I needed to think about it. The Secretary said, “You have two weeks.” I met with her two weeks later. I laid out a vision for what the organization would look like. I’d say, “We’re going to have an investment team, a strategy team, ops, risk, legal, external affairs. We need to find all-star people to lead these teams.” Todd was going to lead investments, Sara was going to lead ops and be chief of staff. “Find those people.”

When Todd took over investments, she was like, “Todd, what do you need?” It was that level of urgency, reporting weekly to the Secretary on how the team was being built. The Secretary designated her most senior person within the Secretary’s office at CHIPS to work full-time on supporting recruitment.

Todd: Her message was not, “I want to hold you accountable.” It was, “Tell me where I can be helpful.”

Mike: She’s very charming. You get her in the room with someone, and she would always close.

Sara: The IG asked us, “If you didn’t workforce plan, how did you decide? Where are your planning documents?” I said, “We got the leaders of each of the organizations in, and we said, ‘Run and find the best people to do the job.’” You could trust that the humans that you put in the seat had the right experience to design this. But that almost struck them as foreign. They criticized it in the report.

I do want to hear more about how you did hire, because you hired a lot of top talent with the capability to execute these deals — talent that usually you cannot get into the federal government.

Todd: We can attract these people to government. I just don’t think we have tried that much.

Sara: We had ample administrative funding and no real Full-Time Equivalent cap — we could hire the number of people that we needed. In the CHIPS Act itself, we had an authority to hire up to 25 people with higher salaries — more than Senior Executive Service roles. It’s nothing like people are making on Wall Street, but it is significantly more than most civil servants make. We also asked for Direct Hire and Excepted Service authority from OPM. They give you an easier, faster process to get folks in the door, and one that gives you more discretion in making your selections.

One thing that is worth repeating — Statecraft recently discussed it with Judge Glock — is that most people in the federal government can’t identify a talented person and say, “We’d like to hire you.”

Sara: That’s correct. In my 16 years in government, I don’t think I have ever had the benefit of having an Excepted Service or Direct Hire slot. It is an enormous advantage. It has a lot to do with our average time to hire, because we relied on those slots, in the first instance, for nearly all of our positions.

On recruiting private-sector folks to government — it is a learning curve for everybody. But having the diversity — people who are not typically in government and people who’ve spent some time there — was pretty magical, and hugely important to our success and credibility.

Todd: We needed different types of people. We were going to have these small deal teams, similar to consulting or investment firms, that would be the Intel or the TSMC team. That drove the kind of people you needed. We needed a senior person that had the experience, the gray hair, and could stand side-by-side with the CEO of Intel. And we needed some mid-level and younger people who were strong analytically, strategically, and financially.

There are a ton of people out there who have a strong desire to work in government and give back — and believe in the mission. We did get a number of close-to or at-retirement people — 30 years at Goldman Sachs, or Lynelle, who worked in the industry for decades and was retired. We got a number of them to come back out of retirement, which was amazing. I think the most impressive thing was to get these young and mid-level people — who were climbing the ladder in the private sector and making real money — to take a risk and come into government. They knew they liked the mission, and they wanted to do something where they could use their skills.

If you now look, the vast majority of those people are back in the private sector doing cool things. Their career trajectories have taken off. They all are going to look back on this period of time as unique and transformational — and they’re back. If more people would feel like, “I could go do something in government for a handful of years and then go back into the private sector,” that would create more dynamism.

Sara: It is also self-reinforcing. Todd, you and Sara being recruiters, and then your senior people being recruiters — that sends a signal to these younger people. “You have real serious people who have experience that is relevant to me.” I imagine that that has to have played a real role.

Mike: Todd and I went on Odd Lots in April ‘23, and we probably had five or ten people who listened to that, thought, “That sounds cool,” and ended up working on our team.

It would be a mistake to say, “We brought in this private-sector talent, and that was the magic.” We also attracted unbelievable government talent. One of the cool things was watching the mutual respect emerge, as people learned to work together. Government lawyers talking to Taiwan at 11pm every night for a couple of weeks to get a deal done — and then being up in the morning to turn the docs. It was incredibly arduous. It is extraordinary what people will do if they feel connected to the mission.

One of the hard things about procedural barriers — whether that’s an internal process design or an external barrier — is you feel it immediately in the team’s morale, because the teams are saying, “We’re trying to do something important. Can’t you solve this for me?”

Over the coming year, we’re discussing many of the lessons you learned in Factory Settings. I think this is a good lesson to end on. You spent an inordinate amount of time actively hiring, and trying to get senior politicals engaged in the hiring. It’s not just that you had on-paper hiring authority from Congress to make these discretionary calls — you have to go and use it.

Todd: Mike used to say, “We need to view the bureaucracy as our dance partner.” It’s not that we need legislation, or everything needs to fundamentally change. We need to work with some of the rules that are in place as well. There’s things that can happen tomorrow without any changes in government. That’s a lot of what we did. We figured out ways to take days out of onboarding people. There are a million different things, but they all add up.

The reason we’re doing Factory Settings — we were having dinner at Mike’s house one night, and he asked me whether I thought we were going to get this done. My comment was, “Yes, but nothing about it seems repeatable or sustainable.” Our goal is to try to impart some of those lessons so that it can be repeatable — it’s not just a bunch of people doing 24/7 for two and a half years to break through everything. Rather, there’s some structure around it that is repeatable and transformational over time.