In this newsletter:

The year in review

Lessons learned

The year ahead

Statecraft on Statecraft

The year in review

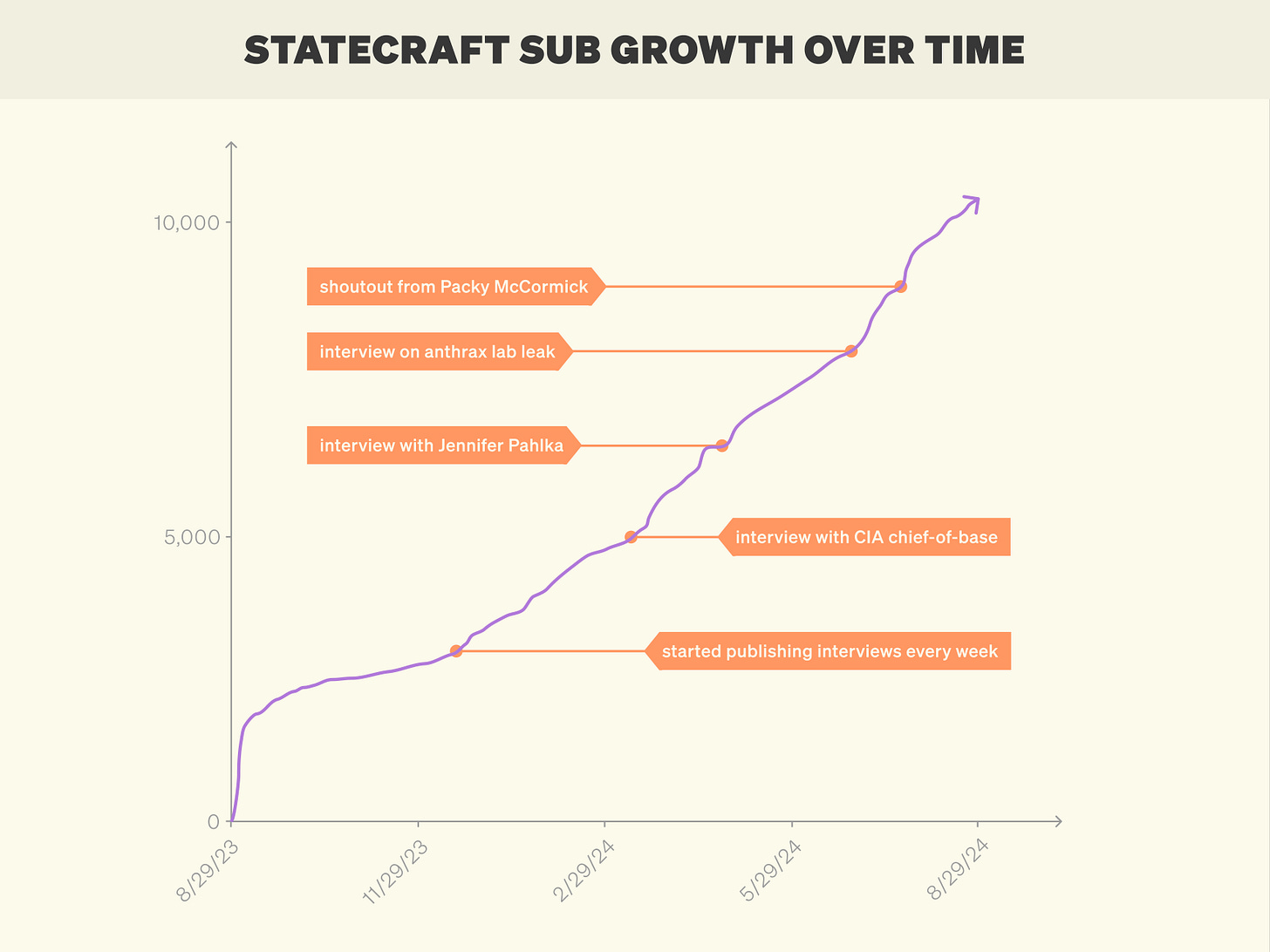

Statecraft turns one year old today! In that year, we’ve gone from a suggestion from a friend (thanks Parth) to more than 10,000 subscribers. We’ve interviewed senior Cabinet members, presidential confidantes, DARPA PMs, historians, CIA agents, and a host of plucky civil servants.

Statecraft is a project of the Institute for Progress, or IFP, where I work. IFP’s support has meant that Statecraft is a free newsletter and will remain one for a long time to come.

In this past year, we’ve done exactly 0 paid media; the newsletter’s growth has been entirely organic. We feel proud of that. Your consistent support and feedback are the secret sauce. If you like Statecraft, please tell your friends, family, and colleagues!

For a printable transcript of this interview, click here:

Here’s Statecraft’s growth curve over the past year:

Lessons learned

What’s worked so far? Here are some lessons I’ve learned over the year, in no particular order:

Building a very large backlog of interviews before launching gave me breathing room to hunt down new interviewees and prep for them. On the flip side, it pushed some interviews slightly past their sell-by date. I could have been more aggressive or creative in restructuring the calendar to keep interviews topical.

On the flip side, being uncompromising about the schedule created useful pressure to just ship interviews.

It helped to kick off the project with an extremely aggressive comms push. We asked everybody and their mother to promote Statecraft.

Ramping up the pace of interviews from 2x a month to 3x a month to 1x per week (our current pace) has juiced newsletter growth.

Readers really like interviews about DARPA and the CIA. Anything that gets to Marginal Revolution or Hacker News does very well.

Readers didn’t much care for our Valentine’s Day and Christmas specials. Sorry, readers – I still think they were funny.

Beyond the above, it’s very hard to know what readers will love ahead of time. Some of the conversations I was most excited about were not smash hits, and some interviews that I expected to fall flat have been very well received. This is probably healthy, on net, in that it keeps me from slipping into audience capture.

The best practices for producing good material depend on the medium. That is, there are all kinds of tips and tricks I followed when we were just publishing Statecraft in print format that no longer apply now that we’re also podcasting.

Interview prep pays off for middle-of-the-bell-curve interviewees. You can take a conversation from fine to fascinating if you’ve done the prep beforehand. Prep can’t salvage a conversation with someone who can’t or won’t tell you the interesting stuff, and the most interesting and charming storytellers are good interviewees even if you’re underprepared.

The year ahead

What’s next?

First things first, we’re hiring an assistant editor: click here to apply. Transparently, I think this is a tremendous opportunity for the right person, who will both work on Statecraft and support the excellent IFP team. I love working at IFP and think you will too.

Even if this is not the right job for you, please pass it along to friends who might be good fits. We’ll pay $3,000 to the person who successfully refers our eventual hire (you don’t have to message us, just have them put your name in the “Who referred you?” section of the application).

What else is upcoming? I think we’ve had a lot of success with this project, but I want to find more ways of opening up the throttle. One piece of that is improving the product. I’m a decent interviewer, but the best interviewers are much better than me. I can improve on multiple axes, from the boring stuff, like enunciation, to the fun stuff, like contesting interviewee claims in real-time. We’ll also continue to hunt for excellent, surprising interviewees (and already have some excellent folks lined up).

There are some “papercuts” I’d like to deal with too, marginal improvements: things like including the PDF/printable version of each interview, or tidying the live transcripts on podcast apps.

We also have a lot of open questions. Should we be leaning into video? Pushing harder to land active political figures as interviewees? Or should we stick to the classics; tight transcripts and maybe a little podcast here and there? Should we share more behind-the-scenes material? Are there types of questions you think we consistently overlook, or types of questions you wish we’d scrap?

We want to hear your thoughts. Take the inaugural survey and help me continue to improve this newsletter! It’ll take 45 seconds max.

Statecraft on Statecraft

For the anniversary episode, we're switching it up: my friend Daniel Golliher interviews me about Statecraft. Daniel runs a remarkable project called Maximum New York; it’s a new civic school focused on governmental mechanics. I highly encourage you to check it out if you’re in NYC, or interested in city governance more broadly.

Thank you to Rita Sokolova for judicious transcript edits.

Daniel: Why did you decide to launch Statecraft?

Santi: A couple of reasons. The proximate cause was a very good suggestion from a friend who said, “Here's an idea: You guys would be well set up to do this, IFP already has an audience and relationships, and there's this great tacit knowledge out there. Can't we make some of it legible? Wouldn't that information be high-impact if you could extract it from people's heads and codify it and ask follow-up questions?” We were blessed to have some of the pieces already in place.

There's a lot of implicit knowledge that you can only get from shadowing someone in their day job or working on a craft, but a lot of policymaker knowledge is not like that. You can make it legible. A lot of that is practices of not just governance, but also how Congress and executive branch agencies work. All of that can be demystified for educated lay readers. We’re interested in not just pressure tactics to make the government do things, but how to make something happen if you’re within the bureaucracy — who do you write to, what do you say, what is legally permissible? The internal sausage making.

Also, there was a market niche. There's a lot of horse race coverage: people are already covering what Mitch McConnell is thinking, what the president is saying. But there's not a ton of coverage of this procedural knowledge outside of trade publications. Plenty of folks in a given industry will get really into the weeds — if you're in geothermal, you likely already know how the Department of Energy works — but a lot of that stuff is paywalled and hidden. It's a huge arbitrage opportunity, even within the government, because the government's massive and there's all kinds of stuff buried in the weeds.

We did an interview on Other Transaction Authority, or OTA, which is a procurement model that some agencies use a lot. Other agencies have the power to and don’t, and instead use much more arcane, difficult, and dumb processes. Plenty of those folks who could use it don't even know they have this authority. OTA is a perfect case: it's not just that the public doesn't know about the topic, but even the practitioners who would immediately benefit don't know about this thing.

The last part is that I think these are genuinely interesting stories that don’t get enough coverage. Many of the interviewees are not elected officials, so they're not as interested or as motivated to tell their stories. You hear about the heroism of people who are running for your vote, but you don't hear about somebody who doesn't need to be reelected in November. There's a lot of good stuff hiding under stones.

Yeah, elected officials are a tiny component of the government; I usually say that government is 1% electoral politics, and 99% governing politics.

How do you select the people you interview? Because as you mentioned, this is tacit knowledge, and many of these people are buried in the weeds.

To start out, we tried to mine our network as much as possible. I'm at the Institute for Progress, which is a think tank that focuses on tech and science innovation policy. Our team has a great network of folks, so I mined that network quite a bit to get recommendations. And I used to be in right-wing news media, so I have some connections over there. We also have some connections from the Obama-era Office of Science and Technology Policy, and those folks have a big Rolodex. Making the funnel as wide as possible in the beginning was really valuable.

Not everybody that we think of, or even reach out to, will necessarily be a great interview. The point is just to generate a bunch of names. As you do your research, you figure out whether this person's got a great story, and whether they can or want to tell it, and can tell it well. You have to filter a lot.

Another key strategy is snowballing interviews. Anybody you talk to for anything, ask them, "Can you give me three names? Who else do you think would be interested? Who would you be interested in reading?" Use every touch point as an opportunity to generate more.

There's a lot of brainstorming about which stories are interesting, and whether there is a person who we can interview about it. PEPFAR, which is the anti-HIV/AIDS program that was really successful in Africa and parts of the Caribbean, was launched during the Bush administration in 2003 —

That was a very good interview.

That was our first. I was interested in it but I didn't know anything about it at the time, but there are widely available oral histories out there. There's a whole set of Statecraft interviews where we started from, “Okay, this is interesting. Who actually executed or implemented this and would be interesting to talk to?”

How far has someone gotten down the funnel before you realize they're not the right person to write about? Have you interviewed someone and then thought to yourself, "We're not going to do anything with this interview"?

There were a couple where I replicated work between interviews and realized that the interviews are very similar because they're parts of the same story. Folks who are either elected officials or mid-career and positioning to go back into government are not great interviews. They're wisely protecting their political capital, so they’re very constrained in what they say publicly.

The model you choose, whether on record or on background, is important. For Statecraft we’ve largely let interviewees see the edited transcript before we publish, but the interviews themselves are on record. Some interviewees will ask for full editorial control before anything goes public. Some of those folks give you a great juicy interview upfront, and then they hack away at the good stuff in post. It's a trade-off — maybe you wouldn't have gotten them at all if you had said, "We're going fully on the record, I'm going to use anything you say." Some interviews end up truncated or worse than you'd like them to be. They still contain a lot of good things, but the delta between what we got on audio and what I was allowed to publish is, unfortunately, sometimes large.

Thankfully the readers don't know about that delta, so we can just enjoy what we have.

That's right. Forget I ever said that.

You can tell that a lot of work and care goes into the process. How long is the pipeline for a post?

I've got a bunch of language for cold email outreach and for responses to warm intros that I use liberally. I think it's good copy, and I would recommend coming up with good language that you can reuse. If I know what I want to talk about with somebody, I'll just say, "Can I book an hour on your calendar?" and make it as easy as possible. If there's somebody who potentially has a lot of stories and you're not sure where you want to focus, or you don't know their area especially well, it’s helpful to get 15 minutes on their calendar to scope the interview, which will often guide the research. I'll say, “Can we get 15 minutes on your calendar next week and we'll find a time to call afterward?”

If people need clearance from their existing agency, that's a long process because press officers and comms folks are not working on your timeline. You’re not their primary customer. That can build months of delay into your process, and you often have to send over proposed questions in advance.

Once we get a date on the calendar, there’s a lot of reading, a lot of copying and pasting stuff into a Google Doc. I don't want to replicate stuff that's already in the public sphere, so figuring out what they've already done is really useful. I highlight potential questions and group them by categories and I tend to over-prepare so that there's lots of good stuff. Ideally, you don't get to all of it because they take one path and you go down that route. I use Descript to record and transcribe, but I think many tools will give you equivalent outputs.

The big time sink is editing. Over an hour, I'll get about 12,000 words in a raw transcript once you cut out the “Ums” and “Uhs.” My rough cutoff for interviews is about 6,000 words — you could certainly do a wide range, but that’s just a personal preference for how long I want an interview and a newsletter to be. So I spend a lot of time going through the raw transcript hacking away at stuff. Lately, I've had a couple of editorial assistants who will tackle that, and that's been a huge help because they've got great editorial judgment. It's good to have another pair of eyes and different opinions about what's interesting. But that can be a day's work depending on the interview length.

I'm finicky about how I want the transcripts to be. If I was less finicky, it would not take nearly as long. I think you could do raw transcripts, and just have it be a podcast first with transcripts as a byproduct. Then you wouldn't have to do a lot of this work.

There are cases where it makes sense to do another interview, either because the person's a great interviewee and I want to get as much out of them as possible, or because I'll realize that the front half was the good stuff and we replicated material at the end.

Have interviewees surprised you in any significant way, good or ill?

Totally. There are some cases where my prep is inadequate and they have a different view of something, or the publicly available information is not necessarily true to their experience. Sometimes people will say, “That thing that's attributed to me was really a team effort,” and they'll beg off a given accomplishment and you have to reroute. Sometimes the claim is, “Yes, I was instrumental in accomplishing this thing, but it was really through a different pathway than Wikipedia and the oral histories and other people will tell you.” Other times, people have a very strong corrective sentence to the popular perception of how an agency works and you don't realize that until you start talking to them and they are at pains to explain, "No, it doesn't work the way you think." Sometimes you can use that to your advantage.

There's an interview with Russ Vought, who was the director of President Trump’s Office of Management and the Budget (OMB), which is the president's taskmaster in the federal government. There's been a long-standing debate between Trump and Democratic administrations about how OMB should be used, its role and authorities, and the value of career civil servants. Sometimes you can get really useful or interesting information by just pressing on that sore spot and saying, “You know, critics say ‘X.’ Would you agree with that assessment?” It's a topic that they've already thought about and there's intense feeling that you can access with the right question.

I’ve said to you many times that I think there should be a New York City-specific version of Statecraft, maybe City-Statecraft? How would that differ from a federally-centered version?

The background state of affairs is that there are fewer and fewer people who are doing in-depth research and public-facing presentations of that research. There are more journalists scrolling Twitter and making a story out of the things they see on there. Everybody talks about the decline of the local news media, even in New York, so I think there’s a huge opportunity there.

One way to do it is to develop yourself as a part-time beat reporter and, instead of just focusing on the interviews as the product, you develop expertise on an individual topic through talking to a lot of folks, showing up at the events, reading through the transcript of the minutes for the council meeting, etc. You can very quickly become the expert on fill-in-the-blank, and that gives you access to stories that you would not have gotten if you were doing the Statecraft version and just talking to a bunch of different people about different things.

Yeah. So that's a generally different model, and not necessarily because it's city versus federal. That's just a different way to approach this.

Yeah, that's right. If you wanted to do even the federal version of Statecraft that's really specific to the Department of Energy, there's tons of value there. It's a question of interest and focus and time.

But you have this list of people, so it's nice to flip through the Rolodex and have a sampling.

IFP, my home think tank, is interested in good governance generally. We want to find stuff that replicates across other domains of the federal bureaucracy and other bureaucracies. That’s preexisting interest, not everybody is trying to get more agencies to use Other Transaction Authority. There's a lot of good material you can draw out with different motivations.

But your audience loves the ARPA posts.

Yes, and, you know, I could succumb to audience capture and do only pieces about the ARPAs, because readers love those and read them twice as much as they read other interviews. You could similarly lean into audience capture locally. What's the sexiest topic in city government? Is it housing?

If by sexiest you mean fought-over, housing is definitely one of them.

Yeah, controversial. A more classic Statecraft model would be pretty easy to replicate. The challenge would be identifying people who can talk. There are lots of incentives for existing federal officials to talk, and they're in the public eye more often, even if they're not electeds, and so they've developed media sense and an interest in being talked about. Even if you're not running for office, maybe part of what makes you enjoy your role as a senior executive official in some government agency is being talked about. That may not be true in the waste management bureau or the equivalent role in city government, but you don't generate headlines the way that important people at USAID generated headlines.

Statecraft has had a lot of success by keeping an eye on folks who are leaving the federal government and trying to grab them as they come out, sort of like an exit interview. How closely can you follow that at the city level?

Pretty easily, I think. And it depends on why someone's leaving. The difference is that people often start in city government with higher ambitions, so just because they have exited the city government does not mean they're ready to talk about it, because they still have their sights on the project. In the federal government, it might be more likely that they’re “done.”

Yeah. Although the revolving door seems common in the federal context — folks will leave four different times over the course of their careers as administrations change or they go take some Harvard fellowship for a couple years. If you're looking to do a bunch of municipal interviews, I think you'll have a different set of challenges getting people to talk than you would doing these at the federal level. I would imagine that a higher percentage of the people you want to talk to are in government currently. That said, maybe there's a similar nonprofit revolving door complex, or you go into consulting or set up your own shop. I don't actually know how you make money after you exit your vehicle.

A group of Maximum New York alumni and I are getting ready to release a very large new dataset that looks at all city council members, going back to the birth of the modern city council: what's their degree in, what did they do before and after the council?

The truth is that many of the current ones don't have experience in the private sector. Their whole life is this revolving door, or they began on someone's campaign and they never left. They entered the government and that's all they know. A city councilwoman just lost her seat in the most recent election, and she immediately got a job with a prominent nonprofit here in the city.

Because that’s what you’re qualified for?

Exactly.

I think there are certain spheres of municipal governance that lots of folks have taken good cracks at demystifying, like transportation costs or infrastructure costs. I think that transportation is really amenable to demystification, because you can do comparative work and say, “Here's what Tokyo and London and South Africa spend on rail.” Ditto housing, you can do comparative work there.

I would be interested in Statecraft-style projects that try to demystify things that are not infrastructure or housing. This is just another idea, but there's a ton of data on policing, and that is not as common to see comparative work on. Waste management is another one — there are many different modes of waste management, but I haven't read the definitive piece on why London does it this way and Los Angeles does it another way. It’s been in the news in New York recently, but it hasn’t seeped into the public consciousness the way that YIMBY ideas about zoning have. There's a ton of material that is ready to hand.

You could also look at contracts. It’s very easy to find interesting and maddening stuff if you look at who the city awards contracts and how regularly they get them? You can even do the private sector version of this, on something like real estate: if you're a tenant or a business, which parts of the government do you encounter? You can develop a real nuts and bolts sense. You talk to five people and all of a sudden you're the guy.

Initially, we did a ton of cold outreach, asking people for warm intros. Once it picks up, you can open a lot of doors by saying, “We talked to X and Y. Mr. Z, wouldn't you like to have your voice heard on this issue?” If you get one high-profile person, the next high-profile person is twice as easy now because you have a title.

Patrick McKenzie said something similar recently, along the lines of “People will respond to you as long as you seem to be the kind of person who can cause things to be published in print.” He was making a point about a particular feature of news media, but it’s true more broadly. If you present as serious and some other bigwig in waste management thought you were serious enough to sit down with, the next waste management interview will be a breeze. That just holds true for any field.

So at the local level, it makes more sense to lean into the beat reporter model simply because that's where you live. That doesn't necessarily seem to be the niche of Statecraft — it’s not about what's going on in D.C. the city, but what's going on in D.C., the government.

Yes, that's a great way of putting it. You would have some advantages doing the beat reporter model with local reporting that you wouldn't for Statecraft, because, where does the DOE work? Everywhere. Where does USAID work? Most countries. The unique advantages of being a beat reporter in a local place are great. The disadvantage is that a lot of people don't want to read this stuff, because the business model doesn't work anymore. On a fundamental level, you don't have as many beat reporters as you used to because people aren't paying for the Milwaukee Journal Sentinel the way they once did.

If you're free from the constraint of trying to earn a living doing this and can do just three hours a week on it as a hobby, then you’re free to run down a lot of leads. It might not work as a formal business model to support your wife and kids on, but that doesn’t mean you shouldn’t do it.

You mentioned municipal waste quite a lot, so maybe that’s a revealed preference of an interest. Do you have a more concrete list of city issues that you would like to see covered in the Statecraft fashion? Are your local interests analogous to your federal interests?

One kind of interview that's really fun if you can get it is how X legislation got passed. It's fraught because that's more electoral than the administrative stuff is.

You're kind of allocating credit in that piece.

Yes, and in a way that people get nervous about, because they either don't want to claim credit or because they do and they may not deserve it. If you write about it, you might piss people off, and now they won't talk to you.

On the bright side, people want to talk about how things got passed. There are interesting stories there and it matters. We've done a ton of work on FDA regulation, like how drugs get authorized.

There are all kinds of equivalents at the city level. Take businesses forming, especially brick and mortar businesses getting off the ground. How do they come into existence? What stops them from coming into existence? Are there pull mechanisms the city can use to encourage business formation?

We cover a lot on R&D for Statecraft. That's less of a state-level issue.

Sure, although there is still significant money in R&D in a locality like New York City. Our city expense budget alone hovers around $110 billion YoY, and that's just the expense budget.

Yeah. Questions about capital allocation tend to get covered in the mainstream media because even people who are not plugged in care about what their city spends. But there’s a lot of interesting stuff about capital allocation implementation. You know, the council gives this department a budget for the year, what does that bureau do that year? You can often get into juicy stories because there are lots of use-it-or-lose-it situations where perverse incentives lead to very obvious bad behavior that everybody knows about but is hard to fix. Those are interesting stories to tell.

I would also love to see some deep dives on the parks — what's the number one challenge that Central Park administrators face? How do you resolve that? How do you keep the public happy?

One of the drums that I always bang on about is that the New York City government is largely unknown to most people, including most of the people in the government. They can't draw you a basic map of the system, let alone a higher-resolution one. It’s the same with the federal government, which is why we need Statecraft.

If you were speculating about the city government, is there something that may or may not even exist at that level that you’re curious about?

I think San Francisco has been a good case study. There's been a groundswell of local interest in doing better coverage of how the city runs, which as a byproduct of San Francisco’s well-documented problems, a bunch of capital, and a bunch of smart, talented people willing to devote time to it.

There have been recent stories about what you might uncharitably call “slush funds,” where the city allocates money to all kinds of non-profits that may or may not do things that society considers valuable. This dynamic of governance through the nonprofit industrial complex is increasingly the norm — I believe a third of the money that goes into American nonprofits and NGOs is federal or local government money. Those stories are very interesting to me because there's a question of democratic accountability and the efficiency of the government dollar.

Those are interesting, spiky, partisan questions. If the government's giving money to a nonprofit, what is the nonprofit doing with it? Did that tax dollar end up somewhere that a taxpayer might conceivably anticipate when they do their TurboTax? If you focus on the arts budget, how much of the money in that bucket actually goes to the opera?

The other thing that I spend a lot of time on with Statecraft, and this is a testament to my colleagues at IFP, is case studies of government effectiveness. PEPFAR is a classic in the global development space — everybody knows that this was, pound for pound, one of the best health interventions that the U.S. has done. DARPA is another example; everybody knows that they invented the Internet, GPS, drones, and led to the smartphone. Cases like that are perfect for Statecraft to get into what actually happened there. People are interested, I'm interested.

One interesting question is, “Okay, that thing works. Why don't other agencies or other entities do that?” So not just looking at what made DARPA successful, but where you see those features replicated across the government. Are there things that we can identify that would make New York better if every department did them? If we don’t see that happening, who or what set or incentives are responsible? That’s a useful line of questioning. If you can identify a good success, what are its children? Where should they exist but don’t?

I think New York has a pretty easy starting point for this, because, as I bet you know, the city essentially went bankrupt in 1975. The mid-’70s were a terrible time that modern New Yorkers probably couldn’t fathom.

I've talked to people who lived through that and the ones who haven't memory-holed it will tell you that it was truly like living in a different world or in a different country and completely incomparable to what’s going on today.

Yeah, many people have a good pocket sense of the city's transformation from the ‘70s through the ‘90s and ‘00s and what Giuliani did with crime, the incarceration debate. That’s partly because it was long enough ago that there's been great debate over what drove it. I read Freakonomics when I was 13 and there's an argument there that abortion led to the crime drop, which got litigated to death. Places where there's scholarly and lay debate about something that happened and who to attribute responsibility to will be more in the public consciousness.

One topic like this that we haven't tackled yet is shipbuilding in the U.S., which has been in decline for ages. There is a huge debate over why we can't do it anymore and who’s to blame. There's rich literature there that you can mine. Global development is another area that has seen a real revolution, thanks to Effective Altruism (EA) folks who are looking at the effectiveness of every dollar. PEPFAR has been running long enough now that you can look at what really worked and figure out how we can do more of that thing. There are some cases where the great thing happened quite a while ago, like the Giuliani revolution twenty-five years ago, and the challenge is, “Can I still find that person? Are they still available?”

Available possibly being a big euphemism there.

That's right. Lots of great potential interviewees are very old. If you know someone who will talk to me about the Giuliani crime drop story, let me know. That's been on the Statecraft list for a while. It’s a juicy success that's widely controversial.

You mentioned that Statecraft tends to focus on administrative achievement and process. How would it be different with a legislative focus?

It's a good question. Some of the relative value of Statecraft is that it's not primarily legislative or plugged into electoral politics. That’s already a very well-covered niche, and a ton of media exists to cover that horse race. Reporters feel obligated to cover it because there's obvious citizen interest. They want a lot of information on what happens in regular increments for when they go to the ballot box, and they don’t need that for administrative stuff.

Another angle that comes from colleagues at IFP, and is an instinct that you share, is that there are ways to influence and improve administrative work that the regular citizen, small policy shops, and think tanks all have access to. A ton of decision-making in our current system happens at the administrative level and the legislature never touches it, or, at least pre-Chevron overturning, just sets out some broad parameters. All of that stuff happens in the agency, and I think that holds true at the local level.

Much of it is very opaque. People have a rough sense of how bills pass. You know, maybe the interest groups are different or the House and Senate power is more concentrated than you thought, but the model is broadly correct. There are tons of pressure groups battling it out, sending memos and missives, and having meetings — what you think of as traditional politics. Agency stuff is just not as clear. Before diving into it, I did not have a great sense of how rulemaking happens. Who wanted it to happen? Did the trade group matter at all? Did the White House get involved? It's really opaque and the public perception of it is totally off.

Often when people look at the government, they see what goes on on the surface and they think that that's all there is when, in fact, there's a whole other game being played on the inside of the government. And those people want support from outside. And so you can help influence the inside game by doing certain things on the outside. Does that ever surprise readers? You know about it, I know about it, but I don't think the public often appreciates that.

Yeah, we've had quite a few interesting stories of how pressure from the top shapes these internal battles. PEPFAR is a classic case where the president and the president's men come in and break up inter-agency scuffles. They say, “The president cares about this. You will do it.” And that resolves a host of problems. Some of the reader feedback we get is from people within agencies saying, “You wouldn't believe how useful the popular press push was on this,” because you can take the Washington Post story and go to your agency.

We did one on reforms to the organ donation system, and it turns out that regular folks pushing for Senate Oversight Committee hearings was a huge unblock there. The hearing alone doesn't really do anything, it’s just Congress and activists trying to generate focus on some issue. It's not an actual rule or statute. But it takes remarkably few people to generate a pressure campaign that can have very big downstream effects.

What's the broader palette of reader feedback or commentary that you get? Besides the fact that they love the ARPAs.

Yeah, they love the ARPAs. Readers call out interviews that are not up to their standard. A couple of Europeans really don't like how America-focused this newsletter is. I put “DMV,” the Department of Motor Vehicles, in a title and I got some feedback that, “I don't know what that is, please pay attention to your European readers,” which is fair. Europeans, we may have some fun updates for you shortly.

I’ve recently gotten some inbound like, “You should interview me,” which is pleasant and useful. Certain topics, like PEPFAR and organ donation, stir a lot of debate because people have a personal attachment. That generates strong responses, both pro and anti.

That sounds like it's coming from people within the agencies. What about the people of Twitter?

People have, remarkably, not been aggressive. We've tried to make this a clearly nonpartisan newsletter. I want to talk to everybody and not have to stay away from controversial people on both sides. I’m interested in demystifying and readers have been remarkably generous to that project. I think that we have good readers who are very interested in why things are broken and why they work. There's a lot of reader feedback that’s like, “Whoa, that makes so much sense,” or “That is f***ed up.” For instance, we talked to someone about how the VA had really, really crappy systems for veterans. I think 10 vets signed up for healthcare on their website.

Was this the thing where the web browser only worked inside the building?

The web browser you had to use to sign up only worked on a particular version of Adobe. No one had any user testing. That story got a lot of interest because people have noticed and experienced those things.

So this sits within IFP. I'm thinking about City-Statecraft, which could sit within Maximum New York. How do you think about these things differently?

They might not be different. In both cases, you're going do this particular kind of project that will give you access to a lot of people, who absent that project, you would not have had access to. Are there ways to use that, to repurpose that access for the broader project?

And it goes both ways — I obviously would not be able to do Statecraft with his caliber of interviewee without the great network of colleagues who know other great people. Find the strengths of the institution that you're working with and playing to those. If you were doing your version of City-Statecraft at the New York Times in 1980 as a new beat reporter on the Metro desk, you'd have access to a ton of excellent resources that nobody has today. You know, we all have access to the Twitter hivemind now. I've found some really good readings that way. I got the email for Matthew Meselson from asking on Twitter. This guy is 93 and really hard to get to, I got bouncebacks from two different emails. Ten minutes after tweeting, I'm writing him an email.

It sounds like you respect your audience and you give them “Just the facts, ma'am” and it's up to them to decide what to do with them. A lot of people succumb to audience capture.

Yes. Better writers than me. It's very seductive and maybe happening to us now. There are more ARPA things in the pipeline, so I haven’t escaped.

But there are different versions of audience capture, like, “We like this subject” as opposed to good guy/bad guy.

Yes. And to be clear, you could do a really good version of that that is opinionated and partisan. People do that and it works. I don't necessarily want Statecraft to be that, but it’s a big world, there’s a lot of smells.

What would you call the model of what you're doing? I just used the phrase, “Just the facts, ma’am. How would you describe the general approach?

I spent some time in the right-wing media ecosystem, which basically exists in response to a sense that existing mainstream media outlets couldn't do “Just the facts, ma'am.” It depends on who you ask, but this goes all the way back to the beginning. Some people think we've never had a golden age and that Walter Cronkite was the high point. Conservative media fills a market need for people who think that the mainstream stuff does not cover the stories that matter, or covers them in a way that provokes a sort of Gell-Mann Amnesia effect.

Part of the Statecraft soup is just that I'm more opinionated with this and more formally subjective in my editorial choices than some outlets are. With Substack, that drives your audience growth because people do want to know what your sense is; they're following you because they trust your editorial judgment or your eye, and they'll leave if they don't like it anymore. There are a few interviews where I argue quite a bit with the interviewee and I'm like, “I'm sorry, I don't buy that. Help me understand.” Some of that is a matter of how they characterize their project and the game space.

As long as you're interested in the stuff you’re talking about, you're going to generate good material. I think that the crappy forms of reporting are often a matter of reporters not being interested enough to get the other guy's sense, even if to tear it apart. They don't actually care enough. Recently there's been a spate of pieces where big outlets totally misrepresented what Christians believe. You can attribute it to a lot of things, but I think it’s that they don't care enough. They're moving on to the next story already. So I would say, don't tackle stories that don't get you a little excited.

So to respect one’s audience, you just need to care enough to find out what you're talking about.

Yeah. I think that's fundamental. People can smell a rat, their noses are really sharp. If you can't be bothered to give something the time of day, they’ll notice.