When I got this episode on the calendar a month ago, my vision was, “Let’s get three of the smartest, most thoughtful liberals I can find on the topic of economic statecraft, and we’ll do a full assessment of the first year of Trump’s second term.” The idea was to take each of the domains — tariffs and the trade war, export controls, industrial policy — and do two things: get an accurate picture of what’s actually happened, and hear how Biden admin insiders and Democratic thinkers see them. Where are there continuities between administrations? Where have their expectations been overturned? And what lessons are they incorporating into their own worldviews?

Then, in a totally novel example of economic statecraft, we grabbed Maduro and seized Venezuelan oil, so we had to discuss that too.

As a result, we’re doing a lot in this episode, and we leave some important questions out: the legal challenges to the current tariff regime, for example. But I think readers will come away from this episode with a clear view of the old and new tools of US policy in the realm of economic statecraft.

Our guests

Daleep Singh is an economist who served in two separate periods in the Biden Administration as Deputy National Security Advisor for International Economics.

Peter Harrell served as Senior Director for International Economics at the White House, jointly appointed to the National Security Council and the National Economic Council.

My colleague, Arnab Datta is Director of Policy Implementation at IFP. He’s also the Managing Director of Policy Implementation at Employ America.

Table of contents

Thanks to Harry Fletcher-Wood, Shadrach Strehle, and Jasper Placio for their support in producing this episode.

For a printable PDF of this interview, click here:

What is economic statecraft?

Daleep, let me start with you. In your post-administration life over the past year, you’ve been working in public using the term “economic statecraft.” What is economic statecraft?

Daleep Singh: It is the use of economic tools, both punitive and positive, to achieve a geopolitical objective. Most people are familiar with the punitive tools: sanctions, tariffs, export controls, investment restrictions. They try to coerce a foreign country or actor to behave differently, because of the prospect of being penalized or excluded from the US financial system — or US technology, if we’re talking about export controls, or trade, if we’re talking about tariffs.

The positive tools are less appreciated, but they’re more potent, because they derive their strength from who we are as a country — our power to inspire, attract, and create. These are tools like investment subsidies, infrastructure financing, price floors, offtake agreements — the tools that you hear about when industrial policy is the conversation. I think we’re out of balance in terms of the frequency and potency of punitive tools, relative to positive. That’s partly why I’ve been pushing for a doctrine of economic statecraft that gives us a chance of more strategic coherence.

You’ve pointed out that there’s been a remarkably quick shift in how the world’s leading powers, especially the US, have gone from using economic pressure relatively sparingly to making it “a default feature of foreign policy.” The number of sanctioned individuals and entities worldwide has increased tenfold since 2000. Whatever the other differences between Biden and Trump, they’ve taken a similar approach to economic statecraft, relative to the approach of the late 20th century.

Say more about that shift and why it’s happened.

Daleep Singh: Starting with the late 20th century — this was the post-Cold War unipolar moment. The notion that many people held was that this was the “end of history,” and we were undergoing a process of ideological convergence. We’ve left that world, and we now are back to the “old normal” of intense geopolitical competition.

Because today’s great powers are mostly nuclear powers, conflict is channeling away from the battlefield and into the arena of economics — including technology and energy — because confrontation in those domains is not existential. I think you’re starting to see all across the world, not just in the US, much more frequent, potent use of economic statecraft, particularly punitive statecraft, to achieve geopolitical goals.

What we’re seeing in Year One of the second Trump term is a maximalist approach to using many of these tools. What we’ve seen in Venezuela is a form of economic statecraft that I’ve never even thought of prior to the last couple of weeks.

We’ve removed and captured a head of state.

We’ve declared that we’re running the country.

We’ve issued an Executive Order that freezes the oil revenue in US accounts.

It seems as though we’re shielding the assets from creditor claims, and we’re now giving the Secretary of State a debit card to decide how to spend the money.

That is an entirely different category of economic statecraft than we practiced in the previous administration. I can give you 10 other examples.

Venezuela

We’re recording on January 14th. Peter, you’ve spent time thinking over the last two weeks about Venezuela. There will be new developments before we publish, but give me your read on the economic tools that we’re using.

Peter Harrell: Venezuela is an interesting case study in what did and didn’t work on economic statecraft. President Trump and the people around him have wanted to dislodge Maduro going back to Trump’s first term. They had this maximum-pressure sanctions campaign on Maduro. They started trying to reduce Venezuela’s oil exports. They had some success in that, and in putting economic pressure on the government in Caracas, but were unsuccessful at achieving their stated outcome, via economic pressure, of seeing Maduro go.

Last year, Trump tried to negotiate with the regime, then seemed to get back to trying to use sanctions to put more economic pressure on Venezuela. They’d done some more designations of tankers, were threatening more sanctions, but it was not working. In the couple of months before Trump started militarily seizing Venezuelan oil tankers, despite the economic pressure, you saw Venezuelan oil exports rising, almost back to where they’d been a year before.

Similarly, last year you saw Iran exporting the same volume of oil it had exported during the Obama nuclear deal — almost 2 million barrels a day — despite Trump saying, “We’re going to maximum pressure on Iran.” What’s going on is that essentially all of the oil from Venezuela and Iran — about 80% from Venezuela, 90% from Iran — is going to China. China, over the intervening years, had built enough of a fleet — we call it the “ghost fleet” or the “dark fleet” — operating outside of US jurisdiction, that the sanctions on ships were no longer preventing the volumes of oil from going there.

Trump had a choice. He could either get tough with China, using economic pressure — we do have a lot of economic leverage still on China — to get them to buy less Venezuelan oil. Or he could start taking the ships militarily. Looking at the failure of sanctions to stop these flows, and his unwillingness to blow up the trade deal with China — because if he got tough with China over Venezuela and Iran, it would probably blow up his trade deal — he chose, late last year, to go back to this 19th-century version: “We’re going to seize the ships, and disrupt trade that way.” I think he gave that a couple of weeks, thinking that maybe literally embargoing the oil in a military sense would force Maduro to go. Maduro didn’t go, he went in and seized Maduro. Now he seems to be asserting that he’s going to have a client local government down in Caracas.

The economics of this are going to be quite interesting. The idea seems to be that the US will broker Venezuela’s oil exports, the proceeds will go into an account in the United States, and Marco Rubio will get to decide what to spend the money on: presumably American agricultural products, medicine, and oil-field equipment.

I think, in a weird way, there is a precedent for this. After George W. Bush took over Iraq in 2003, they did something similar for a couple of years — more internationally monitored, but a similar mechanism. Obviously going in and seizing a leader is unprecedented in modern history. Let’s put that aside. It’s like what went on in Iraq, except it’s unclear what the exit strategy is. Trump may want to do this long-term, and there seems to be much less pretense about normative goals other than controlling the resources down there. That is strikingly different to anything we’ve seen in the United States since at least prior to World War II.

I want to focus on the plan the administration has laid out for what’s going to happen to the oil. Arnab, you’ve educated me quite a bit over the years about the structure of the oil market. Describe the vision for where that oil’s going to go, and how that will affect American producers and consumers.

Arnab Datta: As Daleep and Peter alluded to, this isn’t a new effort of the administration — this was something they were trying in the previous administration as well. But I start with President Trump’s singular focus, which is to get this oil to the market to bring prices lower. That impulse is understandable. Americans regularly cite cost of living as their number one concern. But prices in the oil market are low now. They’re averaging around $2.81 a gallon, which is as low as it’s been since March 2021.

So is this the place to be bringing prices down? There’s a hidden cost to adding more foreign product to the global market and bringing prices down, and that’s our energy security. Since President Trump came into office, his strategy for more oil has been foreign oil production. His first week in office, he pleaded with Saudi Arabia and the Organization of the Petroleum Exporting Countries (OPEC) to produce more. They’ve been producing more. As you go lower, the price becomes too low for our domestic producers to get to break-even points.

For the shale sector particularly — following the shale revolution, which made us the number one oil producer in the world — you get to a level below $60 a barrel where they start to cut back production. The cost of that to American consumers — whether you’re refilling your tank or you’re an industrial producer — is you’re now at the whim of these foreign governments. OPEC, in a year, could decide to cut production. With our domestic shale sector weakened, they’ll be much less responsive to fill that gap. You’ll see prices go through the roof. Pursuing the lowest price at all costs has energy security implications. That’s where I’d fault this strategy.

An alternative approach would be to capitalize on the fact that we have become the world’s number one oil producer and try to build that resilience here at home. To the extent that we are trying to secure more resilience with oil abroad, maybe we should look to countries like Canada — which we already have an integrated oil market with— as a stable country. As Peter mentioned, there’s no exit strategy for us in Venezuela. In a year, if the government falls, we’re not going to have the same level of access.

Daleep Singh: These oil assets in Venezuela are not “turnkey” assets, they’re distressed assets. The estimates are that at least $100 billion of capital expenditure is going to be needed to rehabilitate productive capacity back to where it was a decade ago.

Put a little color on that for us: why is it that you need more than $100 billion to rehabilitate capacity?

Daleep Singh: During the post-Chavez era, investment in the productive capacity of these oil fields has been extraordinarily low. They’ve fallen into disrepair. What we’re talking about in Venezuela is some of the heaviest oil on earth. It requires upgrading of the physical infrastructure to produce oil we can refine in the US. This is going to take years, and probably over $100 billion of capital expenditure (capex). Even if the US government induces Chevron and Exxon to pay for some of this, they’re not going to do so without some form of insurance. A first-loss guarantee, development finance corporation, political risk insurance — these are all examples of positive economic statecraft, but they incur costs to the US taxpayer.

The costs of an occupation — logistics, troops, aid — are immediate, but revenues are years away. There’s a massive mismatch. Then, as Arnab says, there’s the price of success. If the US does manage to resurrect oil production back to pre-Chavez levels, what does that do to the production incentive of shale producers in the Permian with break-even production between $40-60 a barrel? We’re already about to breach below that threshold.

Will you say more about the delta between current Venezuelan production and what that $100 billion in capex would theoretically get us?

Daleep Singh: The best estimates are that Venezuela is producing about 900,000 barrels per day, some outsized share of which is going to China. Only about 200,000 barrels per day is hitting the global market. The ambition is to return production levels — the peak was 2-3 million barrels per day pre-Chavez. That’s what has a $100 billion-plus price tag.

Arnab Datta: To give you one piece about how degraded the Venezuelan oil infrastructure is, it was reported a couple of years ago that their pipelines leak oil every single day: every day there is a separate leak. The idea that US taxpayers would subsidize that production, rather than any number of efforts we could take to boost the resilience of our domestic sector, is pretty absurd.

Peter Harrell: It’s also been interesting to see the news around some of the energy companies being reluctant to go back into Venezuela. Unsurprisingly, it looks like some of the trading houses that are brokering oil have been involved in some of the trades, and refiners will buy the oil.

But if you’re an energy major that’s going to go in and expend capital to try to bring that production up, you’re looking at a time horizon that is far longer than Donald Trump’s presidential term. They’ll need to understand what the long-term political situation in Venezuela is going to be. The last thing they want to do is start putting money in the ground, Trump is out of office, and the assets get nationalized again.

Daleep Singh: Peter, it seems to me the message coming out of Washington to the oil majors is, “If you want to satisfy your claims as a creditor, you need to fund the occupation and reconstruction now. If you don’t pay up, we’re not going to help you recover your seized property.” In other words, this is an ask of publicly-traded companies to act as the financing arm of the US military. That’s a pretty tough sell for corporate boards that have fiduciary duties to shareholders, not to the State Department.

Peter Harrell: That is very much the messaging we’re seeing out of the administration. They are suggesting that if the companies with claims want to get paid, they had better start putting new capital down there. I have no idea exactly how individual energy majors marked these losses, but probably most of these companies — even though they have very large headline claims against Venezuela — marked them down to pennies on the dollar. If you’d asked them a year ago, they didn’t think they were ever going to be paid on this. They are focused more on, “Do we want to put real dollars in Venezuela?” than on the paper value of these claims.

China and tariffs

Daleep, you were talking about the administration’s calculus being this long-running attempt to squeeze Chinese access to oil. You can, in some sense, read the Venezuela operation and the pressure on Iran as ways to try and constrain Chinese options.

How do you think the administration is thinking about this?

Daleep Singh: It’s a little dangerous to describe the actions in Venezuela as purely about resource denial to China — the migration flow and supposed drug flows were a big part of what this administration defined as our strategic objectives. But you can draw a through-line between what the administration’s talking about with the oil in Venezuela — and controlling 30% of the world’s proven oil reserves as a consequence, if we’re “running” the country — and what the administration is talking about, for example, in Greenland, which is the only plausible stand-alone alternative in terms of rare earths and critical minerals that could challenge China’s scale.

If you put those two together, you begin to see more of the contours of this Trump corollary to the Monroe Doctrine: in our hemisphere, we are going to control all of the resources needed to secure our national security and economic growth potential. That may be overstretching the rationale, but when you listen to administration officials, including the president, that’s the impression I get.

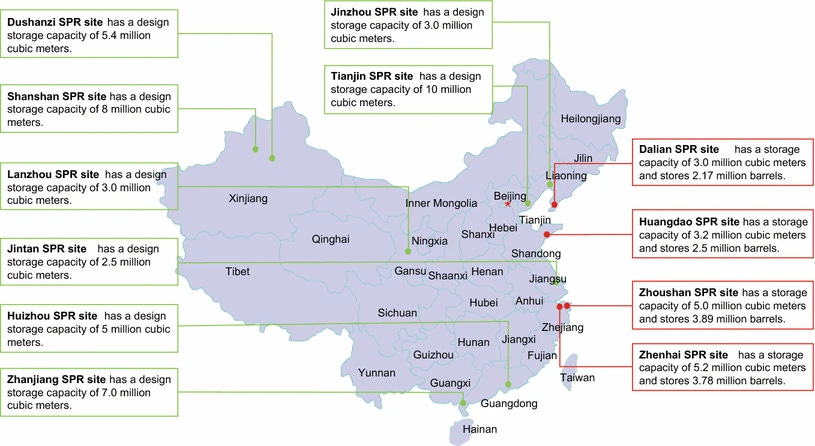

Arnab Datta: China has, over the past half-decade, been making attempts to insulate itself from this type of oil market disruption. They have built capacity for up to 2 billion barrels of crude oil in their reserves. They’ve been building up the stored product in that reserve over the past five years, to 1.4-1.5 billion barrels of oil. Recent estimates have claimed 500,000-1 million barrels per day would be added over the next year or two to those reserves. They are stockpiling. This is a globalized market, so it’s not like you cut them off from Venezuela and they’re not going to be able to access crude any more. They’ve built a sizable buffer stock to weather disruptions, and then they can respond in their own way to secure it with other countries. It’s important to view it in that context — China has been building domestic resilience to this type of effort.

[Arnab and Skanda Amarnath came on a year and a half ago to discuss the American Strategic Petroleum Reserve, a set of massive caves, mostly along the Gulf Coast, where the US stores its own oil reserves.]

Peter Harrell: In the short term, China is one of the world’s largest net energy importers, and as a large manufacturing power, is a massive beneficiary of global low energy prices. I hear this meme, “Maybe long-term, this is about building leverage over China.” I not only think there isn’t a ton of leverage to be gained over the long term, but, in the short run, it’s quite good for China to see more production.

Daleep Singh: One caveat is that China is a massive creditor to Venezuela. To the extent that the executive order wipes out China’s ability to collect oil in exchange for debt service, that is a de facto default. It does give negotiating leverage to the administration.

With China this year, we’ve had tariffs, export controls on high-end technology (which we discussed with Dean Ball), and this back and forth on rare earths. How is this administration picking which tools to use on China?

Peter Harrell: What they’re doing on the economic front is derivative of their overall approach to China. Many of us who watched Trump during his first term thought he would come in quite hawkish on trade policy, with tariffs, on export control, and with other tools, like restrictions on the use of Chinese technology here in the United States. In some sense, that is what he did. China, along with Canada and Mexico, was the first country that he increased tariffs on early last year. Then there was a very brief trade war where we went up to 145% tariffs on many imports, back in April.

But one of the big macro stories of the second half of last year was that Trump decided he wanted a détente with China, something that more resembles a managed trading relationship than a high-pressure campaign.

We’ve seen Trump back off on tariffs. They are still higher than they are on most other countries — although the differential on tariffs between China and countries like Vietnam has gotten small enough that it’s not clear how disadvantageous it is to China anymore. Then just yesterday, on January 13th, they put in the rule finally authorizing Nvidia to sell high-end AI chips to China. We see an administration that has tools that it did deploy earlier this year. But the story more recently has been a much more moderated approach, and a desire to see some, at least temporary, détente with China.

Daleep Singh: I was smiling when you asked the question, Santi, because I don’t have a clear idea of the strategy vis-à-vis China. I could give you a flippant answer and say, “We’re talking about one man’s reaction function,” to use a central banking term. “I want to get on Mount Rushmore, I want to win the Nobel Prize, and I want a dynasty.” The symbolism of a Nixon-to-China — a Trump-goes-to-China moment, might give him objective number two.

China’s had a very good trade war. Growth has held up close to 5%. That exceeds all of the expectations at the start of last year. Net exports are about a third [of that growth]. That’s a share we haven’t seen since the China shock of the 2000s. China is literally exporting their way out of a real estate morass. The way they’re doing that is reorienting exports away from the US — to countries that are transshipping them to the US, the Association of Southeast Asian Nations (ASEAN), Europe, or the Global South.

In the process, China continues to gain global market share in the sectors that they deem most strategic. If you look at ships, cars, drones, machinery, pharmaceuticals, chemicals, lagging-edge chips, or minerals processing, China’s gaining market share, from a baseline of one third of global manufacturing production — more than the US, Japan and Germany combined. To me, that’s a pretty good year for China, in the midst of the largest tariff increase since 1934.

According to The Wall Street Journal, the Chinese goal has been to apply “maximum pressure,” in order to get as close to a full rollback of tariffs and export controls as possible. Doesn’t the fact that they would like to be free from these tariffs say something good about the policy? Should the Biden admin have been more aggressive in its own tariffs? Should I think, “They don’t like it, that means it’s better”?

Daleep Singh: I don’t think it’s especially controversial that the tariffs and export controls hurt China, particularly at a moment when its domestic economy is struggling. The structural weaknesses from the demographic trajectory, de-leveraging going back to the property boom after 2008, and the de-risking that’s taking place — those are all drags on growth. [Statecraft took a deep dive into the Chinese economy with Dan Wang.] External frictions, particularly export controls — the crown technological jewels of the US no longer flowing to China in the way that they used to — harm China’s ability to grow, raise its productivity trend, and escape this demographic trap.

But I wouldn’t go so far as to say that it means it’s all working — because they believe they still have a strong hand, as evidenced by the fact that they were able to get at least some partial licensing of H200 chips in exchange for not very much in return — some soybean purchases, the resumption of rare earth supply, and a trip to Beijing for the president in Q1.

I take your point on the soybeans, but isn’t the resumption of rare earth exports a pretty big deal for us at this point in time?

Daleep Singh: Definitely. But we’re trading chips for rare earths. We’re playing tit-for-tat. The question is, who has escalation dominance? Beijing’s self-perception is that they have greater tolerance for pain, and perhaps that they have more policy space to cushion the downside risks. I don’t think they flinched very much in the past year, and I don’t think the fact that they don’t want tariffs and export controls contradicts that.

I’ve talked to people who would argue the tariffs have done deflationary damage to the Chinese economy. Earlier this year, Goldman Sachs estimated that 16 million jobs in China are at risk due to the tariff increases. We’re China’s number one trading partner. Even if there’s a diversification for transshipping, they still pay some cost here.

What’s your perspective on the medium-term impact of these tariffs on the Chinese economy?

Daleep Singh: The Chinese State Council is much more focused on market share in strategic sectors than they are on monthly Consumer Price Index numbers. Look at China’s trade surplus. Never before in economic history have we seen a manufactured goods trade surplus of $1.2 trillion, which is what China registered last year. If you look at specific sectors, China continues to grow its share [of global manufacturing] in:

Solar panels, it’s 80%,

Electric Vehicle (EV) batteries, about 70%,

EVs, about 70%,

Electrolyzers, 50%,

Shipbuilding, 60%; and

Drones, over 70%.

I don’t know what people are referencing when they say that the more hawkish levels of tariffs have caused lasting harm to China’s own strategic objectives. It may have dented China’s export growth temporarily. But China is still successfully transshipping quite a few of its exports to the US through Vietnam, Malaysia, and many ASEAN countries. It’s dumping its excess supply to Europe and the Global South. The year-over-year growth in Chinese exports to Africa and the Global South is nearing 30%; to Europe, it’s up double digits.

I don’t see any evidence of a domestic manufacturing renaissance in the US such that we can substitute domestic production for foreign imports. I don’t see much evidence that exporters to the US, outside of Japanese automakers, have absorbed the cost of tariffs into their profit margins. I don’t even see any evidence that US importers in tradable goods categories are absorbing the higher tariffs into their own margins. In most cases — think about an industry like apparel or food — margins are very thin. These are highly competitive categories. They can’t afford to absorb higher tariffs into margins, therefore they’re passing it on to consumers. We see that in both the inflation and the growth data.

Arnab Datta: [On the administration’s choice of tools,] the Trump administration certainly believes that they’ve got a toolkit and they’re going to use it in an aggressive way. When you look at some of the deals, for example, the MP Materials deal that they cut back in August, that Peter and I did a deep-dive into, there are different tools as part of that transaction. It’s a multi-billion-dollar deal that includes:

A loan,

An equity investment,

A price floor for mined neodymium and praseodymium,

A guaranteed offtake agreement for finished rare earth magnets; and

A guaranteed EBITDA.

The authorities that they’re relying on for that — the Defense Production Act (DPA) — has never been used in this way, to take an equity stake in a company, for example.

But to pick up on Daleep’s point, what is the purpose of this in the context of critical minerals markets? They’re making big bets in individual companies, but these companies are still operating in a Chinese-dominated market. There doesn’t seem to be as much of a policy effort to reorient that market away from China towards something that is more functioning, free, and competitive.

Where’s the allied partnership? It’s very difficult to go to China’s level of scale. But if you take the critical minerals market, you have:

Everything that we’re trying to do,

The European Union, which is pushing for $300 billion in public-private mobilization to counter the Belt and Road Initiative,

Canada committing $2-4 billion,

There’s hundreds of billions of dollars in commitments to counter China. The US should be serving a coordinating function to build this market infrastructure. But you’re not seeing that. What is the purpose? Outside of cutting a deal here and there, it’s not totally clear to me.

You hear people in the administration sometimes allude to “technological advantage.” They managed to convince the president not to export the Blackwell chip, but they gave this license for the Hoppers. Our colleagues at IFP have written great reports: this could eliminate our compute advantage — the one advantage we have in the AI race. What is driving these two decisions, which are very different?

It looks like the number of Hoppers we’re going to be sending is not nearly enough to substantially erode the compute advantage that we have. That’s probably a win, compared to sending the high-level Blackwells in mass quantities, which was discussed ahead of Trump’s meeting with Xi in Korea.

Daleep Singh: On export control policy, we’re shifting from a strategy of — you can call it “containment” — small yard, high fence around technologies that are foundational for our national security.

That was the Biden administration’s language.

Daleep Singh: That was the term that we used in the Biden years. That’s now evolving to a strategy of monetization. If you want a metaphor, it’s something like a tolled drawbridge. That’s a seismic error. The logic of the H200 deal may sound clever: let’s tax China’s AI growth to fund American R&D, extracting rent from our key strategic rival, while locking them into the Nvidia ecosystem.

But when you look at the political mandate and the engineering realities in China, that logic collapses. First, because lock-in is a myth. Beijing issued a document, Document 79, back in 2022, that legally mandated state-owned enterprises to purge US silicon by 2027. We were debating in the Biden years, “Where should we land on the continuum between de-risking and decoupling?” Beijing was already setting the date for a divorce as it relates to US chips. China doesn’t want H200s to get in bed with Nvidia. They want to bridge the gap until Huawei‘s comparable version comes online. Let’s say that’s late 2027. We’re not capturing a customer. We’re bridging a competitor.

Let me ask about inflation data. So far the tariffs have not been as inflationary as was widely expected in the weeks post-Liberation Day, when every economist I talked to flagged inflation as the core concern.

Peter Harrell: I’m a lawyer — I would defer to Daleep on the economic numbers. But part of the story is that Trump, starting over the summer, began to back off some of his initially maximalist tariffs. We had 145% tariffs in China for a couple of weeks, and then those came back down and steadily ratcheted lower. They’re maybe 45%.

There’ve also been lots of quiet exclusions of products. Trump has talked about tariffs on semiconductors and cell phones. But if you look at what he has done, semiconductors, cell phones, laptops, and consumer electronics are, by and large, fully exempt from the tariffs. Some of the recent data suggests that only about half of the products the US imports have been subject to any new tariffs under Trump’s second term.

There’s a lot of headline noise. It is still the largest increase in tariffs probably since the ‘30s — I don’t want to minimize the impact. But it is not nearly as dramatic as it was looking like it could shape up to be at the beginning of the year, in terms of the value of the product subject to the tariffs. When I look at some of the Goldman estimates, we are seeing some pretty quick tariff pass-through on low-margin products, highly susceptible to the tariffs — furniture and apparel.

Sectors where the margins are tiny, and there’s no slack to eat.

Peter Harrell: The margins are tiny and the tariffs are quite high. Trump has 25% tariffs on upholstered furniture, vanities, and cabinets. You are seeing the pass-through there. But in some other industries, you are seeing companies dragging out the pass-through over time. They didn’t want to get in trouble with the White House by suddenly hiking prices. In some of the higher-margin products, they are willing to eat into margins for maybe a couple of months. But we’re going to see the price increase on those products. 60%-70% will get passed through — but over the course of a year from last summer, rather than two months.

Daleep Singh: Back in January 2025, the effective US tariff rate — taking into account the fact that consumers will substitute lower- or non-tariff goods for higher-tariff goods — was about 2.5%. That had been pretty steady for many years. Just after April 2nd, that rate spiked to 28%. That was the shock-and-awe phase. Then as Peter mentioned, as of late 2025, that effective rate declined towards 18% or so. That was the highest effective tariff rate since 1934, just after Smoot-Hawley was passed.

My conclusion, looking at the economic data over the past year, is this has not been a free lunch:

The vast majority of exporters to the US have not absorbed these tariffs into their profit margins.

We have not seen a domestic manufacturing renaissance in the US that substitutes for foreign imports — manufacturing output has been flat, or has contracted, for 10 consecutive months. We’ve lost about 72,000 jobs in the manufacturing sector.

If the dollar had strengthened, that could have offset the impact of higher tariffs by making it cheaper to buy foreign goods. In the first half of last year, the dollar depreciated by about 10%, which is, on an inflation-adjusted basis, one of the largest declines in the past 50 years.

US importers by and large absorbed the tariff increase. Because these are price-competitive categories, about 80% of those costs — about $300 billion in tariff revenues — have been passed on to consumers. It hit the bottom 20% harder than the rest of the country, because they spend a larger-than-average share of their consumption on tradable goods, food in particular, but also many other imported items. That translates into a 6-8% decline in their inflation-adjusted after-tax income, or about four times more than what you see for the top 10% — they tend to spend more on services which have not been tariffed. For a struggling family living paycheck to paycheck, that has been part of this cost-of-living crisis.

On inflation, I do think we’ve seen a less acute effect, as Peter suggested, but it’s going to be more protracted. Businesses are smart. They saw the April 2nd announcements coming and accumulated inventories to a historic degree — two to three [quarters’ stock] above the pre-pandemic trend. I don’t think we’ve fully exhausted those inventories. In the first half of this year, and afterwards, we will start to see higher levels of pass-through that will impact our inflation numbers and the cost of living. It’s going to have a long tail.

I always appreciate a concrete prediction on this podcast.

Arnab Datta: From a broader investment perspective, our domestic industries are struggling. Every quarter, the Dallas Fed does a survey of oil executives, and they produce rich insights. There’s been consistent consternation about the tariffs over the last three to four quarters. In a recent survey, about half of executives said that at least a quarter of their oil field equipment was sourced from China. The necessity to find domestic suppliers was running into quality-assurance issues. This was affecting their ability to get projects delivered on time. We haven’t experienced the full impacts these tariffs will have.

As Peter mentioned, the tariffs have changed — there’s these exclusions. The general environment is of uncertainty. That is something that’s very difficult for businesses to react to. As these sustain, you’ll start to see more behaviour change as well.

Daleep Singh: To be fair, I can imagine people reading saying, “Didn’t the Biden folks also support tariffs?”

That was my next question.

Daleep Singh: I’m mind-melding with you. Tariffs are a tool that belongs in the toolkit. They are one of the three prongs of a domestic revitalization strategy:

The first and most important one is investment. Make public investments where we want to strengthen and scale up productive capacity in strategic sectors to crowd in the private sector.

Step two: we’re not going to build all the productive capacity we need at home, so let’s work with our allies who are playing by the same rules, invest in each other’s productive capacity, and lower barriers in those strategic sectors.

Three, where necessary to level the playing field, you use targeted tariffs so that our investments pay off. So it was not a tariff-centric strategy in the Biden years — it was an investment-centric strategy.

It’s all a question of balance. I applaud the MP Materials deal. But I don’t want us to create national champions. I would like there to be a portfolio of MP Materials investments. That would have the makings of a more sustainable competitive environment where we can win.

Trade deals

You guys are obviously keen observers. Has the last year changed your views on the use of tariffs as a tool? Have you learned anything that you would want to leverage if you were in the White House again?

Daleep Singh: I have been surprised by how much leverage a maximalist tariff policy gave us in the short term. When I look at which tools in our toolkit for economic statecraft are most potent, I would not have said tariffs. If you look at the US as a share of global imports, we’re about 15%. But China’s share of global imports is about 10%. The EU share — even if you exclude trade within the EU — is about 14%. That’s not my definition of asymmetric strength. We have a marginal advantage in terms of the US consumer’s power, relative to that of other trading nations. It’s less potent as a tool of statecraft than our dominance in finance and tech.

The fact that we’ve been able to use tariffs against our main trading partners, and we’ve not seen any retaliation, I find surprising. Part of this has to do with the fact that the US has been growing faster than the rest of the world — at least most of the advanced economies. Leaders in the EU accepted an asymmetric deal — we put 15% tariffs on them, and they have no retaliation against us — because their growth remains relatively weaker, and they have a relatively higher dependence on external demand from the US. They had a weak hand. But while we do appear to have significant leverage in the short term, we’re seeing the rest of the world hedging to reduce its vulnerabilities to the US over the longer term. That’s my takeaway from what the EU is doing with Mercosur. There are new trading blocks emerging in the Asian supply chain. That’s going to continue.

Peter Harrell: I was quite struck by how readily most of our major trading partners just caved to Trumpian trade demands made by tariffs. The countries that resisted US pressure are all Global South, emerging markets countries.

The European Union — despite a bunch of noise — caved pretty quickly.

Japan, and South Korea, despite a little bit of noise, caved.

Southeast Asia made a very rational calculus. A 20% tariff on something we import from Thailand — there’s not going to be any US onshoring. A lot of these countries concluded, “Fine. The Americans will just pay this tariff for the stuff we’re exporting. It doesn’t affect us much, as long as our tariff rate is the same as our competitor countries’ tariff rate.”

The countries that stood up to Trump have been China, which retaliated hard, Brazil, and India — which have eaten exceptionally high tariff rates and refused, so far to cave, though there is talk about deals.

I would not have necessarily expected that it would be the large emerging market countries that would’ve stood up to this, rather than the close allied countries. Maybe our allies feel dependent on the US for security in the short term, and felt they had to cave.

I have been surprised at how effective China has been, in a short period of time, at finding other export markets. It is striking that China’s overall exports are up substantially last year. As Daleep walked through earlier, major increases — double digits to Europe and 25-30% to a bunch of other countries. I would not have thought that the rest of the world would’ve absorbed that industrial output from China to the extent that they have.

It has been interesting to me to see how little onshoring tariffs at this level have caused. Manufacturing employment is down. Best-case scenario, manufacturing is flat. There’s a lot of talk about US manufacturing — we’re not seeing it in the numbers.

What do you ascribe that to? Is it business uncertainty about the current tariff model?

Peter Harrell: Part of it is the uncertainty. No one wants to invest when they don’t know where tariffs are headed. Part of it is the indiscriminate nature of the tariffs, which have hit a number of industrial inputs pretty hard. Steel in particular, and aluminium to a significant degree, are needed to build manufacturing capacity and are in lots of manufactured goods. We now have by far the world’s highest steel and aluminium prices. That doesn’t, on a cost-competitive basis, help US manufacturing.

One thing we have seen Trump back off on; the Biden administration’s big bet on industrial policy was, we were going to put a ton of federal government money, through grants and tax credits, into clean energy manufacturing. That was beginning to work. Trump has pulled a ton of that back. What we’re seeing is, if you want manufacturing, it can’t just be tariffs. You probably need to lead with the investment, which we are simply seeing fewer dollars of this year, though we are seeing some of those dollars deployed in interesting ways.

I do want to talk about some of the specific country deals. There’s a US-Japan tariff deal, where we established a 15% baseline tariff on most Japanese imports, and they committed to big investments in US strategic sectors. There’s a Korea deal potentially upcoming.

Last summer, when I talked to people around the US Trade Representative Office, the model of what was going to happen seemed to be, “We don’t need to land deals with everybody. We need deals with a couple of the big trading partners — Japan, Korea, one of the big Europeans, India, or China. All these other deals don’t matter. Everyone else will fall in line once they see the model. What matters is landing these deals with Japan and Korea early.”

How would you evaluate that strategy? And what’s the reality on the ground now with these big country-to-country tariff deals?

Peter Harrell: We now have a number of deals out there. There are only two countries where we have what I would consider a fully-developed deal text — Malaysia and Cambodia. With the big trading partners — the EU, Japan, Korea, a couple of others — we have what I might call MOUs (Memoranda of Understanding). We have high-level parameters. Importantly, the MOUs have adjusted and frozen the US tariff rate. They have begun to provide some degree of certainty. In many cases, they did bring the tariff rates down from where they were prior to the deal.

A very large share of our trade does come from our top 10-12 trading partners. If you get deals with those countries, you have covered most of our trade. The other important thing is that, although we don’t have new deals with Canada and Mexico, our two largest trading partners, Trump has exempted 80% or so of our imports from both from his new tariffs, because he said the stuff complies with his United States-Mexico-Canada Agreement deal. It’s not tariffed while he negotiates. That’s also provided a lot of certainty.

So they’re not wrong that you cover most of our trade by nailing down a couple of the big deals. But they are finding it hard to finalize the deals with the big countries. This is going to be the big story of the next couple of months — there’s going to be a lot of friction in America’s trading relationships as they try to finalize the deals.

Which deals are next on the conveyor belt?

Peter Harrell: The EU deal, in which we have an MOU they’re trying to negotiate, but seems very tense now. We’re going to hear a lot of friction about that. I think that Japan and probably the Korea deal will hold. But we’re going to see a lot of friction over the next couple of months with the EU, Mexico, and Canada, which are three of our top six trading partners. The reason is that the preliminary deals, or Trump’s exemption for many Canadian and Mexican products, in some sense gave the other country what they wanted, which was certainty and a lower rate.

But the other parts of these deals beyond the US tariffs are a bunch of things that Trump thinks he got these governments to agree to, or with Canada and Mexico, he wants them to agree to. He thinks he got, as part of the deal last summer, Europe to stop regulating big American tech companies. It turns out that Europe doesn’t want to stop, and does not think it agreed to it. That’s a source of tension that we’re going to see escalate over the next couple of months.

Daleep Singh: There’s a huge opportunity to use this money that’s been committed by Japan and Korea as part of the truce with the US administration on trade, not just for the US, but as a pool of allied capital to compete with the Belt and Road Initiative across the Global South, and in geopolitical swing states that have productive capacity in strategic sectors. Think about nickel extraction and processing in Indonesia, or Active Pharmaceutical Ingredients in India. If you keep it all domestic, it’s going to be perceived as tribute. But if you deploy it globally, that’s a strategic counterweight that more countries could get behind and maybe sustain beyond this administration. There’s upside there.

Arnab Datta: I’m a bit more pessimistic. I’m originally from Calgary, in Canada. We’ve been trying to build export capacity to East Asia for many years. It is the first time I’ve seen this, both amongst the local population and political leaders, described explicitly in terms of “decoupling” from the US. Prime Minister Carney is leaving for China momentarily. On his agenda potentially is testing the waters for increasing imports of Canadian oil and gas to China. [Shortly after this conversation, the countries agreed to explore cooperative oil and gas development and to lift tariffs on Chinese electric vehicles and Canadian canola oil. Carney described the progress and partnership as setting both countries up for the “new world order.”]

Our allies need certainty as well. That’s one of the challenges with this approach. Even if you can get some of these deals with Korea and Japan where they commit to putting up capital, I worry about long-term credibility.

Industrial policy

I want to turn to interesting moves the administration has made in domestic industrial policy. My read is that you guys may have more interest in equity stakes, or some of the other domestic tools being used by the administration, than in the tariff approach?

Daleep Singh: I absolutely agree. We’re back in a period of intense geopolitical competition. If that competition is primarily playing out in the arena of economics, does the private sector by itself have the incentives to invest at pace and scale to compete? I think the answer is no, therefore I am very much a proponent of the US government taking more risk to achieve strategic objectives. Not just loans, but also equity, offtake agreements, price floors, there are a whole suite of tools sitting on the shelf in various agencies. If they’re put to more creative use, it can make a very big difference. My biggest quibble is that none of this should be improvisational. We should have a playbook, and take it as seriously as a doctrine of economic statecraft for punitive tools. We need that same type of rigour for industrial policy.

Let’s take one of these recent deals, the MP Materials deal, which I’m guessing 25% of Statecraft readers are going to be super familiar with and the remainder are going to be, “What are they talking about?” Can I have you guys lay out what MP Materials is, what the deal is, and why has it been so buzzy, at least for the four of us?

Arnab Datta: MP Materials is a company that owns a mine called the Mountain Pass Mine out in California. It’s been in operation since the 1950s — they have made up a lot of our rare earths over that period. It’s also a mine that tells the story of the Chinese era of dominance, both in access to the materials, but particularly in processing — they process over 90% of the world’s rare earths.

In the ‘70s, China set up a Rare Earths Office. They started to accelerate in the ‘90s. They put more effort into dominating the market infrastructure — the means by which a lot of this is priced.

In the late ‘90s, [mining was suspended due to weak prices for rare earths]. Over the course of the next decades, it’s gone through these cycles of someone taking ownership of the asset, putting some investment in, then — when China decides to put more product into the market to bring down the price — bankruptcy. In 2017, MP Materials took over. It had been shipping almost all of its product to China. As the trade war heated up, China instituted a number of export restrictions and [MP Materials] had no customers for their product.

In the midst of that, the Defense Department undertook this extraordinary intervention: they’re providing loan capital and taking a 15% equity stake in the company. They’re putting in a price floor for Neodymium and Praseodymium (NdPr), which is one of the things out of that mine that goes into finished rare earth magnets. They’re also putting in a bunch of capital, in the form of a guaranteed offtake agreement for a new facility for MP that would produce finished rare earth magnets. They’re putting a multi-billion-dollar investment into MP to create a vertically integrated — from the mine all the way to the finished rare earth magnets — national champion. It’s a very big deal. It deploys all of the tools.

Peter Harrell: The US government has, over the last seven months, taken equity or equity-like stakes in more than 15 companies. By equity-like, they have options or warrants that will give them a share if certain metrics are made.

MP Materials, Intel, what are the other ones?

Peter Harrell: You have Intel, where they have a 9.9% stake. The Trump administration has put equity into a number of other mining and minerals companies. One company is called Lithium Americas, but there are maybe eight or nine now.

They’re also doing them in ways people aren’t as closely focused on. Last fall, the administration announced a new, up-to-$80-billion nuclear deal involving Westinghouse Electric and a property manager out of Canada named Brookfield. If you read the Securities and Exchange Commission filings, if certain performance and valuation metrics are met, the government will be entitled to a 20% equity stake in the project. They’re also embedding contingent equity stakes in other deals where equity isn’t granted on day one.

The MP deal is the one where you see the government thinking through how a number of tools can be used together to achieve a desired outcome. It’s not just the Defense Department taking a 15% stake. They have lending for MP to scale up its facilities, and offtake and price floor agreements, to make sure there’s demand for the products.

So far, that has not been the case with most of these other deals. The Intel deal was the government telling Intel, “You had these grants to build fabs. Instead, we’re going to give you a grant to take a stake in your company.” But they haven’t shown any other tools to help Intel build better chips in the United States. Similarly, in some of these other minerals deals, all the government seems to have done is put in capital. Capital needs to be a part, but they haven’t brought to bear the tools that you’ll need to see more lithium refining in the US, for example.

There’s a big philosophical debate about whether the government should be doing equity investments in general. The arguments against are pretty well known. The argument for is that it’s patient capital for technologically-risky, long-term investments. You may get a return for taxpayers; you get ownership in the event that there’s a bailout.

Arnab, talk to me about what might be wrong with taking this company-based approach to these one-off deals. You are generally open to the use of the tool. What’s the risk?

Arnab Datta: It’s important that we’ve ripped off the Band-Aid here and shown, “The world doesn’t fall apart when the government takes an equity stake.” It is worth mentioning one risk that gets less attention. If the government has an incentive in the value of an equity stake going up, does it create cross-policy pressure to maintain the value of that stake? Let’s say a competitor arises — America’s great at technological innovation. If an innovation would wipe out the value of that equity stake, does it mean we’re not going to support it?

The approach I would like to take would be oriented towards building a robust market excluding China. You need to repair one mechanism by which China dominates the critical minerals market: the market infrastructure — the benchmark contracts, the exchanges — which determine how these minerals are priced. If you don’t address that, you’re not creating an opportunity for US competitors to compete with each other, succeed, and get better. When you’re just making a single equity investment in a company, you’re not addressing that other part of the problem.

The market infrastructure you’re talking about that the US should be interested in — what does that mean, for something like rare earths or critical minerals?

Arnab Datta: We should start with, “What are markets and what problems do they solve?” Modern commodity markets, many of which were pioneered by the US and the West, solve problems of coordination and risk intermediation. Metals and commodities can spoil; they’re difficult to transport. If you are trying to get your product refined and transported to General Motors somewhere across the country, a ton of challenges arise. Markets solve a lot of them. They make it easier to coordinate, and to transfer risk to different entities within that chain. Ultimately, the value of that is more investment.

If you look at critical minerals, that market hasn’t developed in the same way. China dominates it, both in production and processing, but many of the means by which those metals are priced are indexed to the Chinese market — Chinese supply and demand. That’s what creates the price pressure on US and Western producers. They can’t get investment because the price is so low in the Chinese market that they can’t compete.

Building market infrastructure, where you took demand from the US and our allies — there’s hundreds of billions of dollars being deployed to decouple from China’s dominance here. If you organize that in a market — where you have transparent mechanisms for prices, and more opportunities for intermediaries to enter and reduce some of that risk in transportation and spoilage, it would make our effort more robust. That’s where I’d like to see more interventions.

The Trump administration does get this. If you look at the deals the President signed with Japan and Australia, the third clause mentions that they want to support the development of liquid competitive markets. That’s a real opportunity. I want to see the execution. I might kick it to Daleep, because we’ve written about this.

Daleep Singh: You laid it out perfectly. What we want is a place where buyers and sellers can predictably meet each other and exchange their goods, or hedge their risks, in a way that’s transparent, fair, and dependable. That’s market infrastructure, and it’s lacking in critical minerals markets and rare earths, in large part because China can dominate supply and push down the price so much so that producers outside of China are no longer solvent.

In your model of good economic statecraft, how do you think about when to use equity stakes, and when to try to build market infrastructure? If we’re trying to build a better market, should we then be picking a national champion?

Daleep Singh: There is a class of investments in projects or companies that require a lot of upfront capital investment, a very long time to generate a commercially attractive return — let’s say 10 years-plus — and that have a lot of risk that investors feel uncomfortable modelling. It could be geopolitical or regulatory — some type of risk that the government knows more about than they do. A lot of these are deep tech or physical hardware investments. The venture capital community tends not to fund these projects at pace and scale. But these companies require equity because they don’t yet have cash flows to service debt. That is the sweet spot of where equity stakes make sense.

You have to start with the why. This gets to my proposed playbook for industrial policy. The sector has to pass what I would say is a two-part test:

Is it critical? Does it power the military? Does it secure public health? Does it sustain a technological edge?

Is there a dangerous dependency? Is the production concentrated in a geopolitical rival, or is it reliant upon a single company at home?

Then you get to the question you just asked: “Why hasn’t the private sector solved this problem?” Usually it’s because there’s some type of market failure. It could be a capital constraint, a demand shortfall, an energy shortage, or the absence of a market where buyers can meet sellers and exchange their goods at a transparent price.

You design the appropriate intervention around the failure you’re trying to correct. There’s a vast toolkit. You have tax credits, loans, demand guarantees, deregulation, skilled labor, and equity. In certain areas of the economy, particularly deep tech, physical hardware, and supply chains that are strategic, equity’s appropriate. But if you invest in equity, you have to also insist on a competitive market and you’ve got to protect the taxpayer. If the public sector is absorbing the risk of a private company, the public should be rewarded with upside if it succeeds.

But you also need strict conditionality to protect the taxpayer’s downside. You should tie the equity injections to milestones that are agreed upfront — construction targets, production yields — and you should have sunsets, because you want the government intervention to be a temporary bridge to self-sufficiency, not a permanent lifeline.

Peter Harrell: One tool we are not talking enough about in the industrial policy debate is concessional lending capital. If you look at countries that have done effective industrial policy — at the post-World War II reindustrialization in Japan and industrialization in Korea — you saw an aggressive use of concessional capital to help companies scale up their manufacturing capacity.

Even in the US, if you look at some of the very first uses of the Defense Production Act, Title III — which is an authority to expand industrial-based production in the US in the early 1950s — the government made 0% loans to aluminium and titanium projects to try to make the numbers pencil. Just as the US has not done equity in recent decades, until last year, we largely got out of the business of concessional lending. Even where you saw, for example, loans in the CHIPS Act implementation [which we discussed on Statecraft recently], they tended not to be particularly concessional.

Not so much for breakthrough technologies, but for critical-base manufacturing capability — whether it’s in the mineral space or the shipbuilding industrial base — we’re going to have to use concessional lending as one of the tools, alongside equity, which serves a different purpose in the corporate lifecycle.

Daleep Singh: You could have hybrid capital where you initially lend, and that can be converted to equity if certain targets are hit — that’s the kind of creative tool we could potentially design in future administrations.

Lessons learned

So far, we’ve been more diagnostic than prescriptive, but I want to open it up. All three of you are influential figures on the Democratic side of the DC aisle. What would you like the next Democrat president to do, based on what you’ve seen of economic statecraft from the Biden admin, and in this first year of the Trump admin?

What will you be championing the next time it comes around?

Arnab Datta: Two lessons I would take from where things have evolved over the last four to five years: one, It’s important for these industrial policy tools to be grounded in an institutional structure that gives the private market confidence and credibility that it’ll be sustained over time. In different domains — energy, and beyond industrial policy, it includes permitting — it’s important that the private sector feels confidence that policy and the use of these tools can sustain over time, and that the discretion that is utilized is something that can withstand changes in administrations.

It’s been harmful for the business community that many subsidies, discretionary grants, and permits have been pulled back over the past year. I also criticized, at the time, the Biden administration for the LNG pause. I would like to see more of these tools grounded in an institutional structure that has some genuine independence — that decisions are being made in a technocratic way —

I can’t believe you said the T word.

Arnab Datta: In a rigorous way that gives the market confidence. The Fed is a unique institution because of how important the bond market is. James Carville said that if he ever died, he’d love to come back as the bond market, because you can intimidate everybody. But that type of a model where, whatever the institutional structure, it’s communicating consistently what its policy goals are and why decisions are being made, so people in the business community can feel that they are being heard and that they have a chance at competition, is important.

My second lesson: It does strike me that the MP Materials deal, which was this robust use of the DPA Title III, it was lauded in a bipartisan fashion. They pushed the boundary of the authority — but you’ve heard three people here talk positively about it. At the time, there was a Heatmap article that said Biden officials are jealous of the deal. That kind of stuff can withstand over a longer period of time if you have that type of buy-in. These interventions should have some level of across-the-spectrum support when they’re being deployed.

One takeaway for me is how much continuity there seems to be between administrations. There are places — like the LNG pause under Biden and many of these different energy pauses under Trump — where there’s not continuity. But there’s also this thematic continuity, from Trump I to Biden, of this new awareness of China as the geopolitical threat. Then, from Biden into Trump II, you’re seeing this awareness that this set of industrial policy tools exists and can be combined in interesting ways.

There are ways in which you see each administration in the shadow of the lessons that have been learned by the previous one.

Peter Harrell: I think of it in two ways. There is a bipartisan consensus now that China is our leading geopolitical challenger — though it’s not a 100% consensus — and that in order to compete effectively, we need to have a fully developed economic statecraft toolkit.

I also think there’s a consensus that is related to, but distinct from, the views of China — that the US should have more manufacturing base in its economy. We got a little too services- and tech-oriented, and financialized. I don’t know if that is the right call from an economic perspective, but it’s certainly a legitimate call that a democratic society can make. If that is the call our country is going to make, just as we need a fully developed economic statecraft toolkit to compete with China, we need an economic statecraft toolkit to have a better manufacturing base here in the United States.

One lesson I would draw from the last year, that I would encourage a future president of whatever party to take — you’ve got to integrate these tools. The lesson of the tariff-heavy approach last year, on most aspects of the economy is, you’re not, by using one of these tools, getting the industrial policy outcome you want.

Second lesson, and I say this having served a Biden administration that was legally risk-averse — you probably should be more prepared to take some legal risks in order to do creative things. The Biden administration tied its hands on some of these issues with an excessively cautious approach to interpretation of authorities — they should be more aggressive.

The third thing, that is not really a lesson for the executive branch, is there is value to being legally creative. Over the long term, if we want to maintain bipartisan support for this toolkit, if we want to have the toolkit be as effective as it can be, and to get ahead of the inevitable governance problems that we’re going to have with all of this, we need Congress to get more active in this space. It’s good for the executive to be creative and go out and lead, but ultimately we are going to want to see some congressional oversight. We’re going to want to see some of this put on a regular footing that will deal with some of the governance issues and force a more strategic approach.

Daleep, you’ve thought about how you would operationalize more robust — I hate using the word “technocratic” — but a system for deciding when to use some of these tools.

Daleep Singh: It doesn’t have to be the next Democratic administration. Most of these ideas have bipartisan appeal for anybody interested in economic security. But for me, the three big ones are, number one, we need a doctrine that lays down limiting principles for the use of punitive economic tools. The frequency and potency of economic weaponry — sanctions, tariffs, export controls — has grown almost exponentially over the past few decades. We need guiding principles to govern, at the highest levels of the US, why, when, to what extent, and for what purpose, we’re using these punitive tools. I don’t think doctrine should stop at our border. Ultimately, and this will take place over the course of decades, we should get on with trying to create a more global framework. It’s the economic analog to a Geneva Convention — not out of altruism, but out of self-interest, because as the anchor country in the global economy, we have the most to lose from an uncontrolled escalatory tit-for-tat using economic weaponry.

The second is, I think we have to institutionalize industrial policy. It’s here to stay, because the private sector doesn’t have the incentives to invest to compete with China at pace and scale. Part of institutionalizing is having a playbook that lays out the strategic objective of each intervention, the market failure, why the intervention addresses a failure, how it sustains competition, and what our exit strategy is. Organizationally, we need a strategic investment fund — with an executive director nominated by the president and approved by the Senate, democratic accountability to Congress, and a technocratic staff — that tries to look at where our strategic opportunities intersect with a private sector deficiency. It’s been done before. The Reconstruction Finance Corporation in the ‘30s and ‘40s led to the “Arsenal of Democracy,” and we can do it again.

The last thing is we need a Department of Economic Security. The National Security Council was created at the dawn of the Cold War. We’re at the dawn of a new era of economic competition. It’s time for an organizational revamp to give us strategic coherence in our use of tools. They’re dispersed — tariffs are at the Office of the US Trade Representative, sanctions are at the Treasury and State Department, export controls are at the Commerce Department. The positive tools are spread across an alphabet soup. If we have a single department, we can strike the right balance between punitive and positive. We can create more connective tissue with allies. We can develop the analytical infrastructure we need to make judicious use of this taxpayer money. That, to me, is how you take economic statecraft seriously.