The Strategic Petroleum Reserve is the world’s largest emergency supply of crude oil. In huge underground salt caverns along the Gulf of Mexico, the American federal government can store up to 714 million barrels, more than what the country uses in one month. Historically, the SPR has been tapped at the discretion of the president when natural disasters or crises cause the price of oil for consumers to spike.

But at the beginning of this decade, prices went haywire: during COVID, they plummeted to negative prices, then skyrocketed when Russia invaded Ukraine in 2022. Colleagues Arnab Datta and Skanda Amarnath proposed a novel idea: what if the SPR wasn’t just used as a stockpile of a commodity? If it used its ability to acquire oil strategically, could it support American industry and calm oil markets?

Arnab and Skanda mounted a campaign to convince the Biden administration to use the SPR more aggressively. Today, we talked to both of them. Arnab Datta is my colleague at IFP, our Director of Infrastructure Policy. He’s also Managing Director of Policy Implementation at Employ America, a macroeconomic think tank committed to full employment. Skanda is Executive Director there.

In this interview, you’ll learn:

Why isn’t the oil in the SPR its most valuable asset?

Why should green energy advocates want to support oil producers?

When is aggressive rhetoric a good idea for policy advocates?

How do you convince a presidential administration to take a risk?

Does elite media actually matter?

For a printable transcript of this interview, click here:

Skanda, how do oil markets work?

Skanda Amarnath: Oil is the deepest commodity in the world and has the deepest futures market. There are different grades of crude oil: heavy, light, sweet, sour, you hear all those different phrases. But oil is fungible. It's a highly globalized market. And oil is highly relevant to macroeconomic outcomes: the most obvious one is inflation. If you think about headline inflation numbers, they tend to be a function of oil prices. So it's part of the material existence of the world, and yet it's also a highly traded commodity. It's highly volatile compared to, let's say, stocks.

The SPR has largely been a “break glass in case of emergency” tool, and historically that means releasing oil from the reserve onto the market in response to particular exogenous shocks. And the threshold for an emergency has been very high. At the historically highest peak of oil prices, which is still the summer of 2008, the SPR was basically not utilized.

There are occasional circumstances when small-scale releases were conducted for small geopolitical shocks, like with the Libyan civil war in the early 2010s, and some national disasters. But by and large, this asset has largely been underutilized. We’ve done releases, but the SPR’s acquisition authority hasn’t been used strategically at all.

Talk to me about how oil producers experience volatility. Why does volatility matter?

SA: There's a famous quote from Exxon CEO Lee Raymond that oil prices on average are $40, but in any given year, they never average $40. Either prices are much higher because of a tight market, or prices crash in a surplus market. You get these big swings in price.

In May 2020 we had negative oil prices. On the eve of the financial crisis in 2008, we had oil prices in the $120 a barrel range. Around the Russian invasion of Ukraine, we saw oil prices spike up again to the $120 range.

And these swings can actually be quite sustained. You can have a long period of low oil prices, and a long period of high prices. Because it takes time to drill for and successfully produce oil, the price you see today is not the price you'll necessarily sell your oil at in the future.

Is that difficulty in finding equilibrium a common dynamic in commodity markets?

Arnab Datta: Commodity markets all tend to be pretty capital-intensive up front. It takes a lot to justify an investment. In the aggregate, each successive cycle tends to lead to more parsimonious investment. We saw this when we had this big boom in shale production, where we became the world’s largest producer. A lot of producers went bankrupt in the price war that followed, when Saudi Arabia pushed a lot of supply onto the market and crashed the price.

If you're a producer, under-investing can lead to a suboptimal return, but over-investment can lead to bankruptcy. When you think about those two choices, it's pretty obvious where you're going to fall.

And we saw this dynamic as prices were rising through 2022. Even after the Russian invasion, investment was much less responsive to prices than it had been in previous cycles. This is a problem that can get worse over time.

So you started developing this proposal for how to use the Strategic Petroleum Reserve. And that proposal grabbed a lot of attention when Russia invaded Ukraine.

AD: If you looked at our pieces online, it would seem like our timing was just perfect. But in reality, Skanda had been looking at the drop off in oil investment that happened as a result of COVID, and was worried about an upside risk if we had this strong jobs recovery. He'd been thinking about this for a while. We explored a lot of ideas that are not published anywhere.

SA: In 2020, we had really low oil prices because of a price war, because COVID had destroyed demand rapidly. Russia and Saudi Arabia could not get along, and it had led to a total glut. You had Ted Cruz saying, “Turn those tankers around.”

Subsequently, oil prices began recovering. But something had changed in 2021: the elasticity of investment to price was not what it had been over the latter half of the 2010s.

A lot of people from 2014 onwards were enamored of the idea that shale had changed the game forever. Shale production in the United States meant, they thought, that we could be a swing producer: when prices weren't sufficiently high, shale producers would come in, invest enough to produce in seven to nine months, and that would keep prices in a reasonably healthy range.

Now, there are ways to monitor that in real-time, by checking different indicators of investment. There’s weekly rig counts, there’s filings from publicly traded companies and so on: and we were just seeing lower investment appetite in 2021.

Before 2020, every time shale production was being scaled up, the price would not be to the expectations and forecasts of shareholders. They basically overproduced too much, relative to where the price was, for much of the latter 2010s.

CEOs and CFOs were explicitly saying, “We’re very good at producing oil. But from 2014-2020, we've been very bad at producing profit and return to our shareholders. Therefore, we are going to be a lot more disciplined about how much we're going to invest.” This is called capital discipline: the idea of highly constraining the outright level of investment to make sure that you will earn a profit. Will you earn the most profit? Maybe not. But will you earn a profit? Yes.

If shareholders don't trust management to be able to produce optimally, it's nice to know that there's a lower bound on profitability, even if you're giving away some of the upside of not scaling up production more.

That's a pattern we had noticed in 2021. There was something going on well before the Russian invasion of Ukraine that made us worry.

That was 2021. Take me to early 2022.

AD: The DOE had announced a tactical exchange of oil in late 2021, so there was clearly interest in doing something with the SPR. We have a suite of ideas that we're kicking around, using several different legal authorities, and then Russia invades Ukraine. With Russia going offline, one of the largest oil producers in the world, that itself was pushing prices way up. A release made sense to address that, but a release is a one-time thing.

That weekend, we put together a memo. We were up most of Saturday night kicking this thing back and forth. The idea we centered on was to utilize the SPR, particularly acquisition in the SPR, to create certain demand for future production.

If you could signal to producers that “We will purchase at a certain price,” that would be enough to create more investment. You could pair that signal with immediate releases now, when prices are very high, to relieve some of the price pressure that folks are feeling as crude oil prices spiked.

SA: There are those who thought, “It's a drop in the bucket. It's not going to matter, and even if it does, you are also destroying the price signal and the investment signal that's vital to getting out of this on a more sustained basis.” And it’s true: there's only so much oil in the SPR that you can release to lower the price, but it does have an effect. But on the investment point, investment in oil production is not just a function of the price today. There's actually uncertainty about the future price. That uncertainty about the future price is not straightforward for oil producers to hedge against, even with deep futures and derivatives markets.

But if you can make investing in the future less risky, that’s an important input for investment in future production. How could the SPR be used to do that? This is where we wanted to push the idea of making a credible commitment to future purchases, which would help unlock more investment even at a lower price.

So you shared this proposal both publicly and with folks in the administration. Walk me through the following year.

AD: The week Russia invaded Ukraine, we happened to be at the tail end of a call with a friend of ours, Alex Jacquez at the National Economic Council (NEC), who said to us, basically as a throwaway, “If you guys have any ideas on oil prices, we're all ears.”

We said, “We do, actually,” and we wrote that memo up over the weekend. That Monday, we sent it over to Alex, Bharat Ramamurti, Vivek Viswanathan at the NEC, and Peter Harrell at the National Security Council (NSC), just to put it on their radar. And we had a number of calls with folks at the NEC to talk through the regulatory challenges they’d face to achieve that.

We then huddled with our colleague, Alex Williams, to develop a public version that was framed more broadly in the context of energy and decarbonization. We were able to generate some media about that piece. And in May, the administration announced the largest release in history: 180 million barrels coming out of the SPR and a huge amount coming from global reserves.

But importantly, in that release, they basically endorsed the conceptual framework for what we were calling for: they were going to explore rulemaking at DOE in their acquisition process that would allow them to do fixed-price forward contracts, which would provide a signal to domestic producers to invest.

SA: Vivek and Lisa Hansmann had given us a call just to say, paraphrasing, “Look, your ideas are getting a lot of traction, and we're going to be working to change the regulation so we can do this kind of flexible repurchase.” That was a sign of confirmation that, beyond a press release, we were having an effect.

What rulemaking tweak were you pushing for, exactly? Could the DOE do fixed-price forward contracts before this?

AD: Prior to this rule change, the SPR’s acquisitions were tied to a market index, and that market index was based on the spot price of that day. Before this rule change, you could do a 9-month or a 12-month forward contract, but the producer would be vulnerable to price risk. Prices may drop by that future date, and the producer is locked into a worse price.

We needed DOE to be allowed to move away from that index system. They could still use this index system, but they could also fix the price at the time of the solicitation agreement. So DOE can put a solicitation out, can agree to a price right now for delivery nine months in the future, and, regardless of what happens in the oil markets, it can commit to acquiring at that price.

This was also something that protects the DOE from upside risk, too. Both sides are getting something useful out of this.

Why was that not in the original SPR mandate? Was it because SPR was originally conceived as just a stockpile of oil for particular emergency purposes?

AD: Some people would argue that. The last time the regulations were changed was 2007, during the Bush administration.

But if you examine the statutory authority of the SPR — which I’ve spent a lot of time with — 42 U.S. Code § 6240, a lot of the language about the purpose of the SPR goes beyond merely storing crude for an emergency. There's a specific acquisition authority with objectives that should be met, like “promoting domestic competition” and “avoiding price harm for American consumers.” The procedures require that acquisitions support maximum domestic crude oil production.

These are all priorities that are meant to be balanced when thinking about the overall purpose of acquisition, and that's right in the statute. So part of our argument was that our proposed rule change was very much aligned with the original statutory intent of the SPR. Specific, statutory language demonstrates that this is not only lawfully allowed, but even required in certain cases.

SA: This is a good example of how legal equilibria sometimes are a function of rational deliberation, and sometimes it's a bit of a vestige of particular premises of the past. A longer-term fixed-price forward contract only makes sense if there's actually an investment signal you want to put out to the market, which requires a market to exist. In the 80s, futures markets were in their infancy.

In May, the administration announced DOE is going to do a rulemaking, so that it can more easily do fixed price forward contracts. In May and June, oil prices and refined product prices are very high.

But a DOE “notice of proposed rulemaking,” which is the step DOE had to undertake to kick off the formal rulemaking process: It just didn't happen. There was focus on a lot of other things. We got a bit frustrated, and we also expressed it externally.

We did a pretty long and broad media offensive to say, “This is a place where we could have a lot of effect on gas prices.” Some people in the White House may have taken that a bit more, uh, harshly than we intended. But it was a moment of conflict.

A fixed-price futures contract for the SPR is the vanilla idea. I will also add that we had more creative ideas. That level of complexity may have spooked some folks at the DOE. We don't have full confirmation here, but we had some ideas that we may have run up against some of the bureaucratic inertia, the general risk preferences of those within the DOE and maybe even at the NEC for something simpler that would not feel as spooky, not feel as vulnerable to error, simply because the change would be so large.

There is definitely a bureaucratic preference for incrementalism, which makes a lot of sense. It's important to have some level of bureaucratic empathy: these civil servants and political appointees are also subject to oversight investigations and inquiries. The Bush administration NEC had all kinds of creative ideas for refilling the SPR whenever there was a release. They were subject to some pretty harsh investigations from Democrats in Congress and the Government Accountability Office, and that effectively chilled a lot of policy innovation and creativity at that time. It's something that can come across on both sides of the aisle.

I think we were successful in patching that up with the NEC, and to some extent also the DOE. Our tone was a little harsh, but it also made a very clear point. The more we went to the media to say, “This is something we could do in the here and now,” the more we could show this was legal and feasible, that it could fit the political constraints the administration was facing, and the economic constraints American producers were facing: the more pressure it put on those who consume the media within the administration.

How exactly did the Biden administration communicate that they would like you to be less harsh?

AD: We hadn’t heard from them after May 2022. Going into July, Skanda had done a couple of podcasts where his tone had shifted more negative.

We got an email from some folks there saying, “We'd love to talk to you about SPR.” We hopped on the phone and some of the folks we'd talked to kind of voiced that, like, “We hear you, we're trying to make this work.”

They requested that we try to be a bit more civil, but they also gave us a pathway going forward. A guy named Neale Mahoney got hired to the NEC, and he basically took over the SPR portfolio. I think some folks had told him to leverage us, and explained the rough contours of what we were trying to do.

Neale was incredibly responsive, and we got more into figuring out the implementation details. Having someone who owned it and owned the relationship with us helped light a fire for them. With any policy advocacy effort from the outside, you want a champion on the inside. Neale became that.

SA: Having him directly involved also helped us communicate the potential scale of impact this could have. At the time, I think the perception was, “Okay, it's a cool idea, but it's really a drop in the bucket. The SPR is only so large, and even if you did all these releases and buybacks, so much oil is produced globally in a day that dwarfs it.”

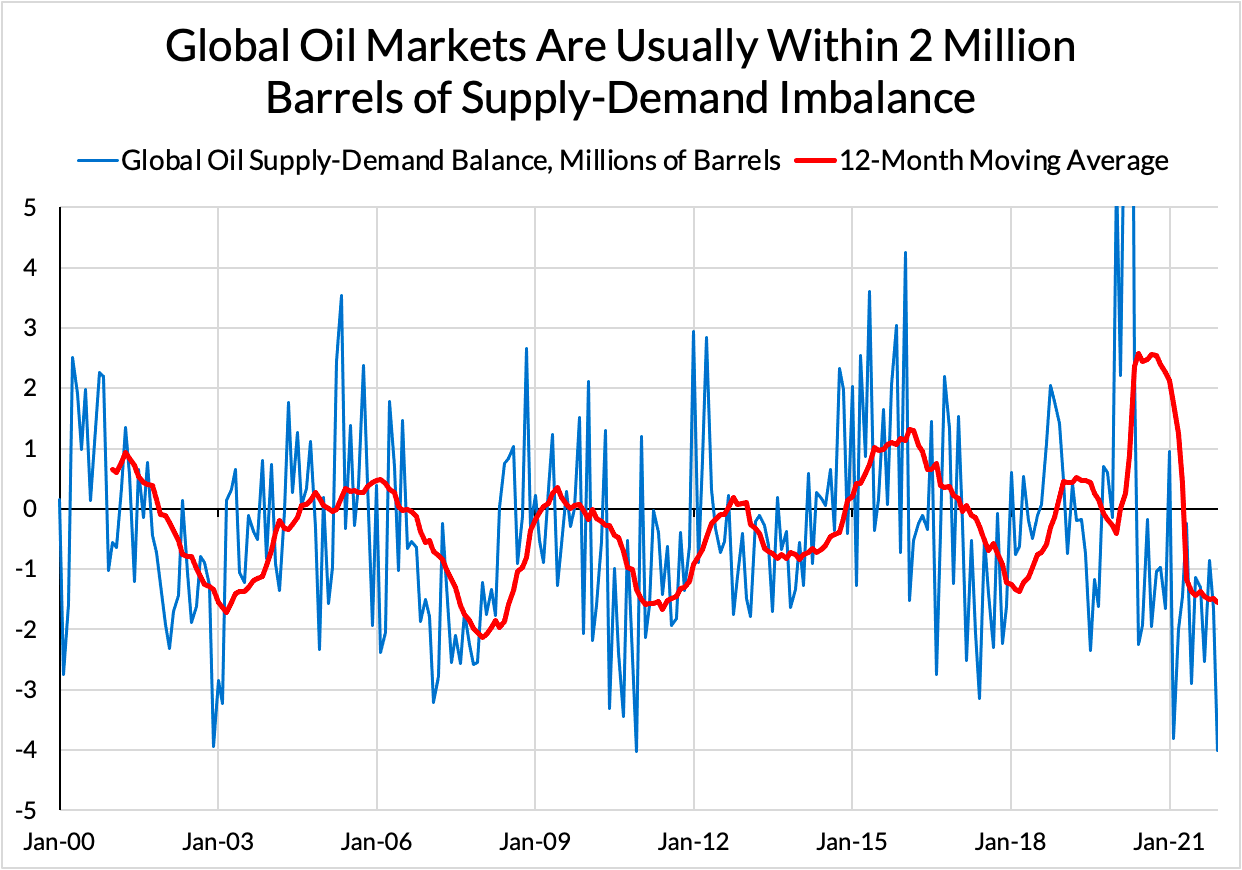

People assumed the SPR is irrelevant at the scale it operates. I don't think that is conventional wisdom now. Actually, what matters for oil prices is what's going on at the margin. Marginal supply-demand imbalances are what matter, and SPR releases and acquisitions could be relevant on that scale, even if that’s small compared to how much the U.S. or Saudi Arabia produce in the aggregate.

That point was really counterintuitive to me when I read it, and I'm guessing it was counterintuitive to a lot of people as well.

Here’s a line from a research report of yours: “The overall size of the market or volume of production does not drive prices. Price is driven far more by the size of the gap between global supply and global demand.”

That seems not obvious until you actually lay it out.

AD: Yeah. That was the first piece in a series we did called Contingent Supply, where we explored a lot of these issues. Both externally and internally, we had to give folks the language to understand this. We don't want to oversell what the SPR can do; this is not going to be the new OPEC. But we have considerable capabilities.

One point we made in that piece was, historically, the asset of the SPR was seen as the crude itself. But as we became the world's largest producer and a net exporter, our vulnerability to fluctuations in crude supply shrunk. The real asset in the SPR is the storage capability, because you can use that to have some impact on the market.

We tried to show people that, even amidst periods of price volatility, the thing that really drives the price volatility is the imbalance between supply and demand. That number rarely gets above 2 million barrels a day. Sometimes it can be 500,000: that changes prices quite a bit.

That's where the SPR becomes really powerful. Theoretically, its intake capacity is 685,000 barrels a day. That's not a small number. That can move prices in a considerable way if you can take in the oil. There are logistical challenges associated with doing that. But the number of barrels you can take into the SPR is something that directly affects the market.

SA: One key thing: oil storage is not a trivial consideration. Oil is typically stored for inventory purposes on a short-term basis. Storing oil for a long duration requires specialized capabilities. The SPR has these massive underground salt caverns for storage, but it took time to build those out. Long-duration storage is not generally super economical for the private sector to invest in.

Because it's hard to maintain those facilities?

SA: How much do you have to spend to build those facilities, and what return will you get on them? You’d need an ungodly amount of leverage for something super capital-intensive, generally not a wise idea. And you’re not going to deliver a huge return to shareholders from creating private-sector salt caverns.

This is a pretty special capability that the U.S. has available. Vacant storage has its own value, because in the event of particular price and supply conditions, it can be a contingent acquirer of oil.

People think that the barrels of oil in the caverns are the precious bit. But they’re not. The precious bit is the fact that you have salt caverns that can store oil for long periods of time. This was something really underappreciated.

The notice of proposed rulemaking finally came out in July of 2022, so there were about two months before that during which we saw some interest in other policy ideas that struck us as a lack of focus.

But folks like Brian Deese, for example, were very invested in seeing this type of policy come to fruition. He pretty clearly had read our work and understood the intuitions. The notice of proposed rulemaking came out alongside some released information about the SPR, and you saw in the language about it that there was a clear understanding that if we buy back oil for the SPR in a smart way, we're also helping support oil production in the United States.

You definitely saw the administration take a more affirmative posture that U.S. oil production is part of the solution here, which would have been very foreign to the ears of anyone on the 2020 campaign beat. To get more folks to say that was a clear marker.

The White House had actually told us, “You may not be happy with this.” The truth was, we were very happy! What they had done was very minimal changes to language to open up a lot more optionality.

The regulation did change things quite substantially, in terms of opening up the aperture for how you could contract for the oil that gets refilled into the SPR salt caverns.

SA: In the rulemaking process, we were the only ones to submit a comment. We were pretty constructive, and it's reflected in the final rulemaking. And when that final rulemaking was announced, it was also announced with an important policy commitment: the White House said, if we hit the $67-72 range for West Texas Intermediate (WTI), we will be a buyer [West Texas Intermediate is a grade of crude oil used as a benchmark for oil pricing]. We will be a repurchaser. That's effectively what these fixed-price forward contracts allow you to do: make a purchasing decision in response to price.

To our mind, there are some problems with picking a particular level of prices when doing this, but it is a statement of policy that makes the market more confident about a certain range of oil prices.

They did that in October 2022, alongside a suite of other policy measures, including the Russian oil price cap. And OPEC itself also committed to some production cuts.

AD: At this point in October, we’re in a period where the administration's made this commitment that we're going to buy. What that buying will look like, we don't know, but they're going to buy.

We're communicating to the administration: “DOE needs to be ready. If you've made this commitment, you need to be ready to buy.” We were getting pushback: “Even with this rule change, it’s still difficult, there’s all these implementation and logistical risks.”

A lot of our work over that period was trying to understand how you could manage some of these risks, so that when we were saying, “Secretary Granholm, you need to start purchasing,” there was some weight behind our thinking. “We know this isn't easy, but here's a number of different ways to manage it.”

What specifically were you trying to derisk for policymakers?

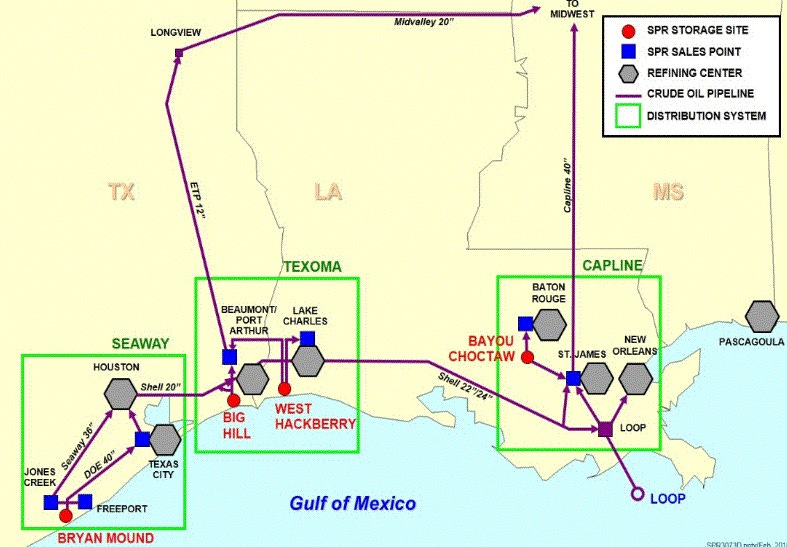

AD: Broadly speaking, there are physical barriers you could call “delivery risk.” Stepping back, the SPR is four physical sites. It's not one thing in one place, and it can’t just take in oil. There are challenges associated with grade: you can't co-mingle sweet and sour crude, for example. If you're taking into one site that's storing a particular kind of crude, that's the only type of crude you can acquire.

Over the past couple of years, the SPR has been undergoing something called the Life Extension 2 Program. It’s a series of maintenance changes and improvements that Congress has appropriated money for. So different sites have been closed at different times. Their repair timelines aren’t always the most stable. So committing to acquire nine months down the line is challenging when you have to manage all these different constraints.

We tried to socialize the power of the administration’s own rule with the administration. If you're doing these kinds of fixed-price contracts, you essentially can separate financial settlement from physical settlement. You can commit to a certain acquisition at a certain time. But because you’re providing the purchaser the money, you can offload some of the risk associated with delivery to them.

The DOE has incidental contracting authority that you can read in the SPR solicitations that allow it to manage this risk in certain extreme exigent circumstances. We tried to communicate that, if you're upfront about that, the producer can just price that risk in.

That was the powerful logistical point we were trying to make. There are ways to design all this optionality into your solicitation itself through an auction design, but you can also set delivery terms that allow you to manage situations.

If there's some crisis at the Bryan Mound storage site and we need to go to Big Hill because we want to use the pipeline to the Nederland Terminal which is connected there, you have the flexibility to do that. You can compensate the producer for that risk by pricing it into the solicitation.

Cut to December 2022: DOE does a pilot buy of 3 million barrels. How did that go?

AD: Not great. It resulted in no acquisition. What happened was, they announced this pilot, and a lot of the bids that came in were priced a lot higher than what the market was. So they didn't acquire any oil.

So you’re doing all this work, but DOE’s pilot in late 2022 goes poorly. My impression is that in the early months of 2023, DOE is slow-walking. It’s not necessarily game to use this authority in the way you’re describing. Is that right?

Yeah, I would say so. And understandably, right? News stories chase failure. What we tried to communicate was that the reasons those bids came in high were extremely identifiable.

The pilot solicitation had this two-week period where your bid was required to be firmly open. That essentially exposed the seller to this one-sided optionality on the part of DOE. If there was price volatility in that period, the seller would face substantial opportunity costs. You could imagine them saying, “If we have to have a fixed price bid in for two weeks, we're gonna put our bid in at the highest end, because we're married to that price.”

Bids essentially came in $10, $15, $20 above what the West Texas Intermediate price was at the time. Changing that two-week period was an identifiable easy change for them to potentially make.

But you actually kind of want this failure. You want them to test out different means. We even wrote a piece where we said, “Here are some other things you could pilot.”

You know, these are low costs. Certainly it takes staffing resources, and I don't want to minimize that. But no acquisition happened. It's not like they lost money or they spent too much on something. We tried to celebrate this: we’re figuring it out, and if you can make this one change it'll probably work out better.

You’re saying the downside of the pilot failing is that it feels embarrassing to try to buy oil and not buy oil. But we didn't spend any money. We can try again. We can run it back.

AD: Yep. See if you can design it better and try again. It really is a low-cost exercise. It was exclusively reputational downside, you get a little bit embarrassed, maybe that it didn't work out, but it should be a catalyst for learning, right?

But if you read the public statements made by Secretary Granholm, by different officials within DOE, there was definitely a sense of getting snakebit, feeling very skittish.

The DOE said, “We have maintenance to do for the SPR. We have these mandated releases for 2023. So don't expect us to come in and buy oil,” even though the president had made a statement of policy in October 2022 that when the price is low, we're gonna buy.

You were getting a lot of downright excuses to say “We can't buy, because of physical limitations.” But part of the definition of the regulation was that you can separate financial from physical. You can buy now, while physical delivery can be later.

You pushed back very hard on DOE at the time. I'm looking at a quote from you in March 2023: “With oil prices in the president's ‘SPR repurchase zone’ for two weeks, the DOE should be embarrassed that there was no serious intent or preparedness to give credible service to the president's commitment.”

You didn't pull your punches there.

SA: Yeah. That was probably our harshest tone, but also our most precise criticism, and I feel that it stands up. Oil prices were in a much lower range, at that $67-72 range, and for two weeks there was radio silence from DOE. For us, you have to be willing to at least say, “We stand ready if these prices stick.”

Obviously, oil is volatile: if it just dips for a brief minute, I'm not sure that's itself a good signal, but when it's there for two weeks, you probably should be ramping up plans. We were very, very sharply critical.

I think, to be fair, policy also started to go through a bigger shift. We had put a lot of pressure publicly in the media. We also expressed our concerns to the NEC. Lael Brainard (current NEC director) and (White House chief of staff) Jeff Zients were pretty on top of the president’s SPR policy commitment and the importance of credibility. You can't just unilaterally decide as an agency, “Well, I don't want to respect this commitment at all.” It was a presidential commitment, not an agency commitment. You have to do your best to make this work.

To be fair, the DOE eventually came up with some of its own solutions about how to address the vulnerabilities associated with the pilot. By May of 2023, we started to see it announce a more innovative, solicitation process that was the first real fixed-price forward contract.

There have been additional developments to make sure that process is more consistent and sensitive to price, so that it's not just an ad hoc process. Anytime prices are below $80, they are a buyer. They're not a huge buyer, but they are a buyer.

That acts as a stabilizing function when prices are lower and when supply-demand balances warrant a little extra demand to keep prices in a stable range.

This move also worked to juice investment. I have a quote from you here: “Planned investment more than tripled in the months after the announcement of forward contracts, even though prices were falling at the time.”

You read that as a success for SPR, right?

SA: Yes, I would say it's certainly where policy helped reduce the implied and realized volatility of oil prices. That itself is a very underrated and important input.

In 2022, there was a lot of talk about, “Why would I invest so much when there's going to be a recession right around the corner?” There was a certain recession fatalism in the vibes, but also just in terms of what business leaders were saying explicitly, which was: “If oil prices are just going to spike and then crush the consumer, do we really want to be investing a lot in production? Or do we wait for the recession to happen and only then ramp up investment?”

Investment expectations ramped up in the fall of 2022 when oil price volatility was falling. Now, how much of that is SPR? How much of that is the Russian oil price cap? How much of that is OPEC? There are different ways to weigh it, and I think there's good reason to put weight on those other two policies too.

But I do think the SPR has had a very positive impact. When prices have fallen into the $70s and $60s, we have seen the SPR step up increasingly. There’s just more confidence that when you get to those scenarios, thousands and thousands of barrels of discretionary demand is coming back.

I want to pull out some lessons here: One is about politics. You touched on the pushback from the left wing of the Democratic coalition, “Why do we want to be in the business of helping oil?”

When Trump proposed refilling the SPR in 2020, Chuck Schumer called it “a bailout to big oil.” How did you navigate pressure from that part of the Democratic coalition?

AD: We made a clear, credible argument for why price stability is important in the context of decarbonization, in an industrial policy project. If we're constantly going through a boom and bust, from $40 to $140: for one thing, prices at $140 a barrel hurt a lot of people. There is a group of activists who would celebrate $140 because they think people will stop buying oil. We don't really see that from the evidence. But it also just hurts a lot of people. It makes it harder to buy other important things.

And when prices are very low, you tend to see more purchases of gas-guzzling vehicles when prices are low. You have to think about oil in that context. This isn't something we're going to get rid of right away. This transition has to be managed, and we were able to make that argument credibly enough that people bought into it.

SA: In terms of the meta lessons here for policy advocates: there's a tendency to get into the “I'm right, you're wrong” game. And look, on the merits, I think saying “Keep it in the ground” is not a very wise policy. Yet it was the norm in a lot of Democratic circles. So when we first released this policy proposal publicly, we invested the time up front to try to explain our case to that audience.

Alex Williams helped us rhetorically approach this in a way that takes a “steelman” view of what climate activists might say. I was really proud that we had interest in seeing this policy succeed among people who are very clearly on the left, as well as people who are very clearly center-right. Those political economy considerations are pretty important.

You guys were very successful at doing what I’d call elite media. You were on Odd Lots, in The Atlantic, Eric Levitz at New York Magazine, Matt Yglesias’ newsletter, Catherine Rampell at the Washington Post wrote a lot about this.

My question is twofold. How did you manage to socialize this idea in those places? And was it important? Did it matter?

SA: I think it does matter. That's how it gets on the radar of people within the administration, quite frankly. We had some inherent advantages because we're an existing macroeconomic policy shop. We had a lot of those contacts precisely because they viewed us as a useful intellectual resource.

Everyone's got bias when they're presenting information, but I think we really do try to strive to be descriptively accurate. When the facts feel a little uncomfortable for us, we're going to acknowledge it. If you are trying to change policy, you have to be seen as credible on some level, unless you think a reporter is going to basically be your mouthpiece.

The ability to pull out new, reasonably neutral information on capital discipline, for example, helped people understand this more complex idea. We had a good description of how businesses behave without lurching into canned lines. If you don't have an understanding of business behavior, especially on a real-time basis, that's a problem.

We also probably benefited from the fact that there was a bit of a vacuum among left-leaning thinkers for good ideas about oil prices and oil markets. It was a lack of interest in general. There was a sense of, “Oil is bad because it emits greenhouse gas emissions, and this is clearly bad for the climate.” But beyond that, there was also a sense that anything you do only matters on a 5-year horizon, because oil was historically more long-cycle. But the game had changed. If you can give a good sense of why businesses are averse to investing, even though prices are high, you might actually get some interesting answers, and that might help you understand how to change policies.

I often hear a similar idea on the right: “We don’t have any good policy guys on these areas. No one is filling these vacuums.”

This seems like an interesting case on the left, where some of your ideas felt counterintuitive to fellow coalition members who don't follow oil markets, and so no one was working on them. But the ideas map to how the markets actually work.

SA: The notion of there being a policy space here is often itself a foreign concept. People will say, “Oil markets are oil markets. It's a random walk of prices. What can you do?”

Sometimes it takes a certain “policy entrepreneurship approach” to find out what’s actually feasible: What could a general counsel sign off on in terms of changing a regulation? Where does the agency actually have authority? Would this regulation revision stand up to many different statutory interpretations? We tried to use that type of knowledge alongside the economic and market sensibilities.

How do you think about the effectiveness of the more aggressive tone you sometimes took? There's a fine line between useful pressure and throwing yourself out of the coalition. How do you think about balancing that?

AD: One of our contacts on the inside has described us as “helpfully annoying.” You want to be annoying at the right times to push them. With the harsher communications we did have, we tried to be more precise, and we had the credibility of having done the work. We weren’t working backward from a catchy slogan or something.

That probably made it easier for folks on the inside to tolerate some of the negativity and annoyingness. I think precision allows you to take more rhetorical risk.

You don't need to take the view that conflict is inevitable, or that you always need to be super critical to get anywhere. But sometimes you do! Sometimes it helps the internal champions to have something to point to externally. That happened on a few occasions in our advocacy.

Some people have taken victory laps of sorts on the SPR. Matt Stoller said SPR has “broken OPEC,” and I’ve seen similar language from folks on MSNBC. What do you think of that kind of rhetoric?

AD: It's not rhetoric I'd feel comfortable adopting. Saying this is going to crush OPEC is hyperbole, although I get that there's a reality to politics that will go beyond what we can really guardrail.

The SPR can be helpful for market stabilization, even though, really, the thing that has a lot of power over market stabilization is the cartel itself. That’s not to say OPEC has always operated with a firm eye toward market stability, but Saudi Arabia and some of its cartel partners can achieve more market stability if they want to. OPEC is a bigger fish.

What we're trying to advocate here is not necessarily contingent on OPEC being broken. The policy is defensible on its own without that. There are good reasons to do this that insulate you from some of the lack of governance associated with OPEC. The cartel frankly still has a lot of power, control, and authority over what happens in the oil market.

SA: This is kind of how I feel about the rhetoric of, “Keep it in the ground,” or “We’ve got to stop all drilling,” or whatever.

Now, the tactical hyperbole is to say the SPR is this all-powerful thing. It seems a mile away from where we were at the start of this, which was to say, “The SPR is this trivial asset that has no real bearing on oil prices.”

You guys wrote one of my favorite case studies on how public policy affected a given industry. It's a joint piece for IFP and Employ America on “How Public Policy Accelerated the Shale Revolution.”

Arnab, you also wrote a piece with Daleep Singh in the Financial Times on other applications of the SPR model: how you can use it for critical minerals, for instance. Zooming out, what's the lesson from all these policy ideas for state capacity?

AD: There's a couple things. We analogize with the Federal Reserve. Though it’s not a perfect institution, it has shown a willingness to use a wide and varied range of tools to preserve stability in a given market — in its case, the financial market.

One set of tools is to prevent crises ex ante. And one set is to mitigate crises after they've happened ex post. Before a crisis, they use certain supervisory and regulatory authorities. They have capital requirements, they do stress tests to indicate where vulnerabilities are. These are all intended to ensure that, if there's stress in your bank, it doesn't turn into a full-blown crisis.

But they also have a set of tools that when markets crash: to inject liquidity, to purchase assets, to be the lender of last resort.

In the context of commodity markets, we could imagine a world where you're doing a bunch of different types of policies to prevent crises, to ensure that there's not a price shock and that we're getting enough production. That might be lending tools, it might be the kind of price insurance tool we’ve discussed with the SPR, so that producers have the kind of certainty they need to produce. If a crisis hits, like we saw in lithium at the end of last year, where prices for spodumene went from $6000 a ton to $800, you could have someone serve as the buyer of last resort, to lift that price to a level where mines at least can stay online.

That’s a framework we're trying to apply to some of our commodities approach, but we have to work with the federal government we have. It'd be great if Congress re-imagined the SPR into something broader, but until then, we have to look at tools like the Loan Programs Office domestically, or the Exchange Stabilization Fund at the Treasury.

SA: This is an area where there’s a lot of opportunity for superior policy development, relative to what I'd say was the status quo and status in state capacity in the United States. We tend to do everything on a very ex ante basis. You do a rulemaking, and you keep that rule cemented forever. You set the regulation in place, you don't touch it at all. And there's a reason for it, right? You want to give businesses and regulated entities some certainty. But we don’t tend to do contingency thinking and analysis in the same way.

We want to actually think about the unlikely outcome. Don't tell me it's unlikely, so it's not going to happen. Tell me, if that happens, are we prepared for it? Are we prepared for an environment in which oil prices may go to $200? What exactly is the playbook in the event of markets crashing? What should the Federal Reserve do? Just saying, “Well actually, the implied probability of stocks selling off 50% is negligible.” Sometimes that's not a good enough answer.