At the end of January, the Trump administration pushed out a top Treasury Department official after he refused to give DOGE access to the government's vast payment system. We're talking to him today. It's one of his first public interviews since leaving the civil service.

David Lebryk was the highest-ranking civil servant in the Treasury Department and one of the most senior civil servants in the entire federal government. He was responsible for overseeing the Bureau of the Fiscal Service, which puts out more than 90% of federal payments every year. That’s more than a billion transactions and more than $5 trillion.

Lebryk did not want to go into the blow-by-blow of his leaving the administration early this year. We discussed a number of topics I think you'll find highly relevant:

How the Bureau of the Fiscal Service works

How it prevents fraud, waste, and abuse

Why DOGE’s plans for Treasury won't work out the way it intends

Thanks to Emma Hilbert for her judicious edits and to Emma Steinhobel for graphics.

For a printable transcript of this interview, click here:

David, you've spent 35 years in civil service, most recently as fiscal assistant secretary. You oversaw the Bureau of the Fiscal Service, or BFS. I wasn’t familiar with the BFS until recently. What is it, and what does it do?

We prided ourselves on not being a household name. We’d say that if the public knew what we were doing, it meant we weren't doing our jobs.

The fiscal assistant secretary is the senior career official at Treasury, and we oversee some of the most important functions of government: financing, making payments, collections, accounting for government-wide activity. When you go back and look at the founding of the Treasury Department in 1789, these are the core functions. “It shall be the duty of the Secretary of the Treasury to digest and prepare plans for the improvement and management of the revenue, and for the support of public credit; to prepare and report estimates of the public revenue, and the public expenditures…” That’s us.

We're responsible for making sure that every month, 70–80 million benefit payments get to American beneficiaries. We're responsible for operating the Treasury auctions, which are not just about financing the government: they're also the foundational element of the world financial system. We're the organization that is responsible for administering a network of collection boxes and mechanisms to bring money into the Treasury general account.

And we're responsible for reporting on the financial activity of the government. In the immediate office of the fiscal assistant secretary is the cash forecasting function. We have about 10–12 people — and I would argue they're the best in the world at what they do — who look at regular outflows and inflows to ensure the government has enough money on hand to function. This becomes very important when you get into a debt limit situation.

You were the fiscal assistant secretary. That role is one of the most senior career official roles in the government, right?

It is the senior-most career official at Treasury. There are very few other assistant secretaries at the career level throughout government.

Will you just describe how the BFS works in more detail? As I understand it, at least 90% of all federal payments, including Social Security benefits, tax refunds, and payments to federal workers, all run through the bureau.

In Civics 101, Congress passes a law and appropriates money to an agency. An agency then gets an account set up for it [at Treasury] that says, “This is the amount of money that you have available to spend, and you can spend up to your balance.” For our purposes at Treasury, it’s really important to have that information centralized, so that you know what's coming in and out of the government. We have control over the Treasury general account, but the individual decisions about who gets paid and how much really have to reside with the agency.

And a certifying officer at an agency certifies that a payment is a legitimate, authorized payment.

The agency says, “Yep, this is on us, we're making this payment, this is the amount, this is the person,” etc. It's our job then to make sure it gets into the payment system and to the end user. We’re the processor of the payment. We did about 1.4 billion of those payments last year.

That's incredible. What kinds of risks are you trying to avoid in that system?

We are under constant threat from adversaries trying to exploit vulnerabilities in our system. That’s one reason we're quite comfortable being under the radar — we don't like to be too visible. Besides trying to compromise your system, they can also try to extract information from your system. We have enormous amounts of private data in our enterprise: things like bank account information, names, addresses, sometimes Social Security numbers.

You're very careful about who has access to the systems. When we make a change to the ongoing operation, you can only go into the system for a singular purpose. You can't go into the system and see more generally, because of the importance of making sure there's continuity of operations.

We run continuity of operations exercises and we take that stewardship role very seriously. I'd like to think that we're among the best in government, if not in industry, at protecting our systems. These functions are core both to the federal government and to the world economy, so we have to be on time, every time, and we worked very hard to make sure our operations were world-class.

That’s one reason government isn't flexible. A challenge I would face as a leader is that we need to have repeatable processes. To go in there and try to play with those systems or to be innovative with those systems carries a lot of risk attached to it.

Talk to me about fraud prevention.

I worked on the implementation of the DATA Act, which passed in 2014 was really about giving the public better access to more granular information across government. Now, in the private sector you monetize data — you take consumer data and you attempt to turn that into business. I was always somewhat frustrated that we weren’t able to make great use of so much data in the Bureau of the Fiscal Service — you don’t want to necessarily monetize it, but how do you turn that data into better decisions?

The best example is fraud prevention. Last year, we put together a tiger team — a cross-cutting team that could look at the issue differently. We had an existing program called Do Not Pay.

Describe that Do Not Pay system.

It’s a series of databases. In the payment process, an agency will send over a file that has not been certified yet. At that point, we run the payments through the Do Not Pay system to see: Is it a dead person? Is it someone who’s been disbarred? There are a variety of other databases in there that can flag, “Pay attention to this payment.” The system sends that information back to the agency, and the agency has to adjudicate it.

Last year, we determined there was an opportunity for us to do a lot more. We entered an agreement with the Department of Labor to share data across the country in federally funded, state-administered programs. If someone's trying to commit fraud in California, it's likely they're trying to commit fraud in some other state.

Currently, very few people are looking at that. We entered into a similar agreement with HHS with Medicaid data, so states now report on who’s on Medicaid. Cross-referencing that aggregated data gives you insights you would never otherwise have. In the first year of the program, we went from $650 million of fraud prevention up to $7.2 billion.

In addition, during the pilot process, we looked at 19 additional data sets. If we ran our payments through these different databases, we came up with another $30 billion of fraud prevention.

What kinds of fraud would you be catching in those data sets?

In some cases, it’s very simple. You applied for a program and said you were a corporation — well, we could match against a public database of incorporated companies.

We entered into a discussion with FINCEN about suspicious activity reports data that they're getting from the financial institutions. We also started to match against account verification, which is to say, banks have a “know your customer” requirement. If you're sending a payment to a bank, you probably have a higher degree of confidence that the payment is going to someone who should get it.

Now, we knew we would never be able to build data models to the same extent as private companies. So we also turned to the private sector to see if we could run our data through their tools, and had some pilots that showed promise as well.

Ultimately, our vision was that every government payment should be scored. In the same way that your credit card payments are scored, we should be able to assess the risk of fraud in every government payment.

At Treasury, we felt we were best suited to provide these services to agencies. If you're in the unemployment program, say, your job is effectively to try to work with constituents to get unemployment benefits out. Fraud is not your top priority. And even if it is, you don't know where to begin. And you're not funded. You have a deep set of barriers to actually taking fraud seriously.

We thought BFS could provide these centralized services to agencies to really drive down fraud in government, and I think that the plan we put together is outstanding. I mentioned the $30 billion. I think that's on the low end.

Just to get these numbers straight in my head: Your initiative with this tiger team saved about $6.5 billion in prevented fraud. You think there's a roadmap from that initiative to prevent at least $30 billion in fraud every year in federal payments.

Yeah — I think you gotta be careful about the “every year.” If I prevented fraud in Year One, do I get to count it in Year Two? But yes, I can assure you that $30 billion is the low end.

Give us a rough pie chart of what you think that $30 billion of fraud is.

There’s people stealing Social Security numbers. You have issues of applying in multiple states. Big banks and credit card companies will tell you, if someone is committing fraud in one part of the enterprise, you can be pretty sure they're committing fraud somewhere else in the enterprise.

Today, we don’t have any mechanism to say, “I've identified someone committing fraud in this program — are they committing fraud in another program?” and trying to say, are they committing fraud in another program along the way?

When a payment gets a red flag, we don’t go and look at every other program that they've applied to.

Absolutely not. This is where data matters, right? This is where you can “monetize data” in the federal context. Now, one reason we didn't move as fast as we could have is that you do have things like privacy and computer matching agreements.

You've had folks on from OIRA. On this account verification system, something that was proven and piloted, it still took 10 months for us to get approval from OIRA on that. I don't know how long it would take us to get those datasets approved to get to that $30 billion.

And there are good reasons for that. I am a big, strong privacy advocate. I really do believe that we need to protect citizens from government overreaching. I firmly believe in that.

I also believe that we at Fiscal have proven we’re responsible at protecting people's data and managing that data responsibly. Now, the reason we are good at it is because we train people not to have a Privacy Act violation. One way you get a program stopped is to have reputational risk of not doing it well.

In my career, whenever there's been a glitch, you do hear stories about how someone couldn't pay their rent this month, or they couldn't buy medicine that they needed. From that standpoint, you need to make sure that people who deserve the payment aren't stopped.

This is where a scoring system would help. If a payment shows a high score, maybe you make the payment the first time, but then you go back and you look hard so you don't make the payment the second or third time. You don't compound the error and make that payment 12 times a year.

Speed is sometimes important, right? During COVID, I was responsible for helping get the money out quickly, and it's one of the most important things I've done in my career. But you had two choices. You either get the money out quickly with some risk of fraud, or you get the money out slowly and eliminate the risk of fraud. I believe the decisions made at that time were the right decisions, given where the country was, but I also had an enormous amount of frustration that I could not raise my hand in those meetings and say, “You can both get the money out quickly and not have fraud.”

I remember this vividly, because during COVID, my roommate was the one team member at his bank authorized to run PPP loans through the system. We’d sit next to each other at the dining room table and he’d push loan applications through the system.

What could we have done better to avoid fraud and keep that money flowing?

We turned off the Do Not Pay system. There was an inspector general report that said, if those outlays had been run through the Do Not Pay system, $1–2 billion in fraud would've been prevented. We ran into situations where monies were being paid to entities that either had lost their incorporation or had not been incorporated at all.

And this is one of the paradigmatic kinds of fraud from the PPP era, right? People just making up corporation names.

Exactly. We knew if we had crosschecked with existing corporate records, those corporations would not have shown up.

The employee retention tax credit had the exact same set of circumstances, where there was just this demand to get payments out very quickly. Some of the screening and filtering had been dialed down.

Would imposing that filtering have meaningfully slowed down payments in those two cases?

During COVID, yes. Because we just didn't have the robust databases and the ability to run these things quickly that we really need. But I think we're building something right now where the answer will be no. It’s not an either-or. They're not mutually exclusive.

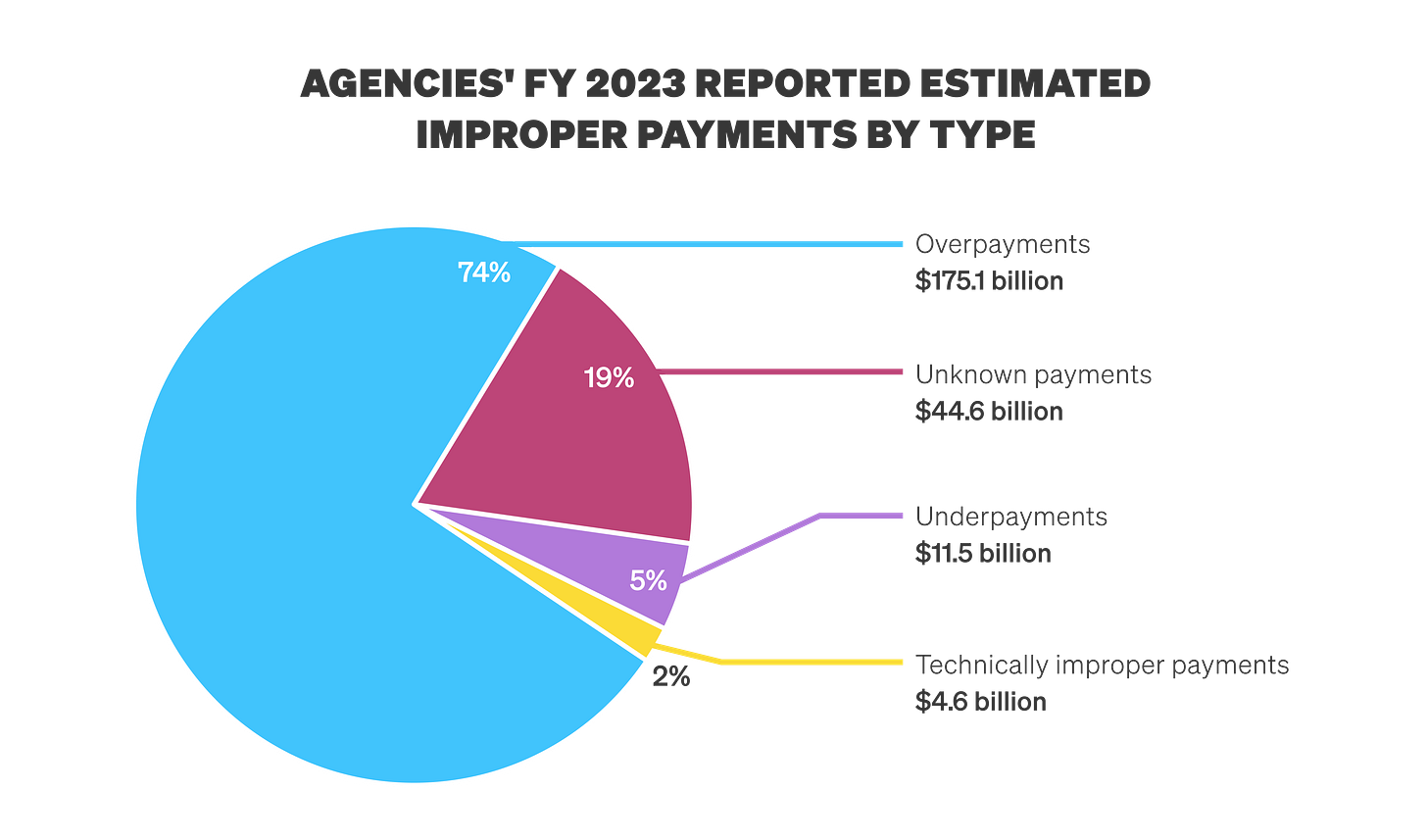

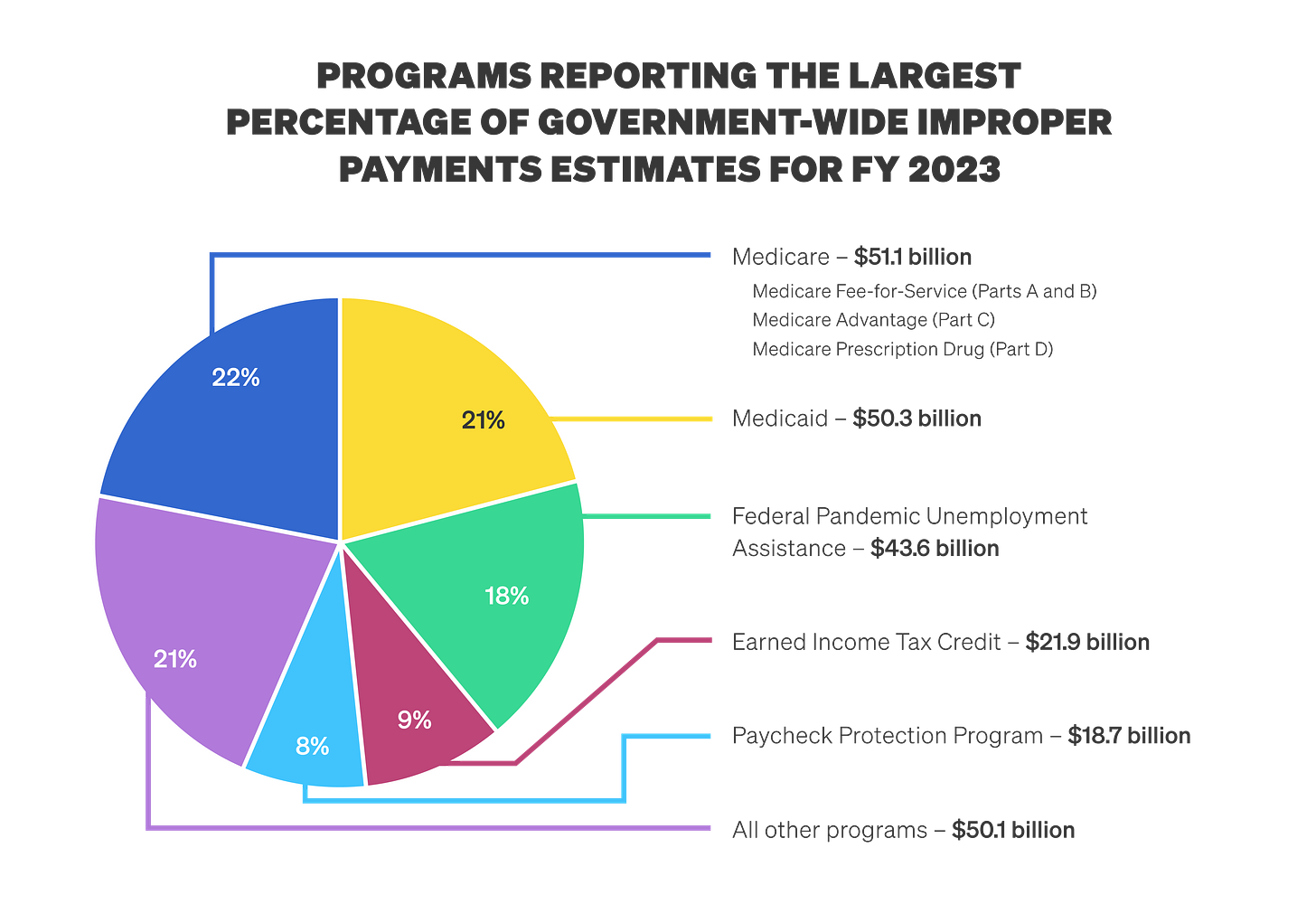

I've got a Government Accountability Office (GAO) report in front of me — it’s one you’ve seen before. It estimates that in the 2023 fiscal year, the government made $236 billion in improper payments, and three-quarters of that, roughly $180 billion, were overpayments.

GAO notes that the federal government is “Unable to determine the full extent of its improper payments, or to reasonably assure that the appropriate actions are taken to reduce them.” Can you put some color on that for me?

That report was very controversial within the executive branch when it came out, for a number of reasons. You need to make sure to distinguish between an improper payment and a fraudulent payment, right? An improper payment may be: the documentation isn't there. A Medicare-reimbursable claim may not have all the paperwork perfect. There are instances where you know you're going to make that payment, and hope it reconciles later. That’s not necessarily an indication of fraud; it’s an indication that there’s not appropriate documentation. You’re going to hope that reconciles later.

Now, there are instances of fraud in the Medicare program – definitely room to examine more closely. But Medicare may cover an electric wheelchair, or something really significant. Do you stop its issuance because you don't have every T crossed and I dotted? Most of the program people would say no. You want to get that needed benefit to the beneficiary, and make sure you reconcile it later.

But as we also know, “pay and chase” is a bad idea. You want to make sure you get it right the first time. So GAO definitely has points about improper payments and the need to do better — they identify four or five major programs in that report to focus on, and I would agree.

The level of fraud is not well known. But in the private sector, you see estimates of 2–5% fraud rates. Now, in the federal government, you’ve got to be careful about your denominator, because interest payments on the debt are a major chunk, and they’re not vulnerable to fraud. But if you went and looked at a lot of the individual programs, I wouldn't be surprised if 2–5% is an overestimate of what you're seeing in government.

In our prep call, you mentioned that people in the new administration were not especially interested in your fraud prevention work. Is that fair to say?

I think that it's fair to say that where the fraud focus has been is not what we've been talking about.

Where has it been?

Well, I think that you’ve seen a number of stories on USAID, and a number of stories on stopping payments more generally, under the thinking that the payments are fraudulent.

My sense is that there's been a focus on more general notions of fraud, rather than more specific notions of fraud.

If you were road-mapping the federal government's fraud prevention, what would be in your top five list?

More access to databases so you can do better data aggregation. I personally have a bias — I would give more authority to Treasury and say, “the Secretary of the Treasury can make determinations about databases and more ability to centralize this function clearly in Treasury.” I would be mandating that the states provide data on the state-administered, federally funded programs, and ensure we're aggregating that data.

That is, if you get money from the federal government to run a program, you have to report back certain data that states currently don't report back?

Yes. And I would say you must use Treasury services. Right now, 50 states do it 50 different ways. If the states knew that they could bounce their payments files off of our databases, and we would give them back information about the prospects of fraud in that program, you would see serious, significant improvements in fraud prevention.

Also, in fraud prevention, there are best practices — certain things you can build into the design of your program to minimize the risk of fraud — but many federal program managers don’t look at that. We did this with the electric vehicle tax credit, we said, “Before you actually do this, make sure the entity's been incorporated. Make sure it’s a legitimate bank account, if you made a payment to that bank account in the past.” You can do program design that helps minimize the potential for fraud.

That might not show up as fraud prevention, because you don't know what you prevented, but it would significantly reduce the amount of fraud in state and federal programs.

DOGE is much more focused on slashing and burning than it is on building new systems. But let’s imagine a push to build systems comes later. How should people in the federal government be thinking about that day after tomorrow?

To some extent, what's happened here is not unusual. New administrations come in and have new ideas, and quite frankly, sometimes they don't think that the people running the organization have very good ideas.

I have a good number of friends in investment banking. I asked them, “If you had a leveraged buyout or a takeover of an organization, what tends to happen?” Well, the first thing that tends to happen is what we've seen here, which is you cut. Your theory is you've got to reduce the size of the organization and make it more efficient. You keep cutting, and it's not unusual to say, “Okay we've cut too much at this point. We’ve now got to actually build back up.” And they sometimes will bring people back in.

But where it's different in this situation is that, in the private sector, to use a simple example, you have 100 employees and you bring it down to 60 employees. Those 60 employees now know that the bonus pool is divided among fewer people. They have strong incentives, they're committed, and they know that there may be some payout on the other end. We don't have that in government. We're in government because we believe in the mission, and we believe in what we're doing.

The other characteristic of a good takeover is that you engage the top people and the experts, because they know how the organization works, the opportunities, and the costs. You make sure that you can bring in great new talent, and you lay out a business plan about what you’re trying to accomplish. Many of those elements are sorely lacking in what we're seeing today: both the well-integrated plan, but also the level of alienation that’s occurred in many of these organizations. I talk to federal employees, and many of them are extremely disheartened and just don't know when the next shoe's gonna drop. It’s going to be very hard to build something when the organizational mindset is not about growth and getting better, but one of anxiety and outright fear.

And you say that as somebody who has led RIFs, layoffs, and restructurings within the Treasury Department before.

Yeah. One of the toughest things I did in my career was consolidating two bureaus. It was not popular at all. I learned that you have to have a business plan: You have to be able to say a vision of where you want to go. And you have to communicate with people about where you're going and what you're trying to do.

Final questions here, Dave: do you see the Bureau of the Fiscal Service as a purely executive branch function, or, given Treasury's history as something of an organ of Congress, do you think it's got a quasi-legislative function?

Throughout my career, when a new policy was sent in my direction, my job was first to understand that policy direction, and then to understand what the legal authority was to do that. And then the third task was figuring out, “Do I have the operational capability to execute it?” What we do in Fiscal is really driven by the authorities that we have. I've always been comfortable with that. Given our role, I might want more authority in areas like fraud prevention and the like, but by and large, I see us as taking direction from that enabling legislation.

The system I mentioned, those a hundred political appointees who come in, we benefit from outside thinking tremendously about looking at something differently. Now, what I would say is that most political appointees don't come into government to think about operations.

They come in with a very ambitious policy agenda. But in the end, the success or failure of an administration is in large measure determined by their ability to be effective. Can they execute that policy agenda?

They're going to inherit an apparatus, career people, technology, and a budget. They mostly don’t understand these things, and so they struggle on the implementation side.

Vision without execution is hallucination. You've got to be able to execute that vision, and you have to think about how you translate vision into actual results. Our system tends not to bring people who have operational experience, and that's why the interface between career and political appointees can be so terribly important.

Will you run through the laundry list from your personal experience? What have you experienced as an overregulation of you doing your work?

So absolutely the delivery of human resources: CFR Part 5, if you want to get technical. There are three major issues that you face on the HR side. One is: you're asking a manager to navigate a system that they don’t often use, to hire someone maybe once a year. So they mess up. They're not disciplined. They don't know what to do. So you've got a bad set of rules and regulations.

You have managers who really don't know what they're doing. I had a person who was really good at hiring a team up fast, got the right people in place quickly. She focused intensely, just bird-dogged things, making sure that she got those things done. But the average manager's not gonna spend that amount of time doing that because they’ve got other things going on. That's a real problem.

The Bureau of Fiscal Service will probably hire 50 accountants every year. Why don’t we have an open and continuous vacancy announcement? So when it comes time to hire that accountant, we just pull that accountant from the list, rather than putting out a new vacancy announcement and going through the whole process again.

OPM [the Office of Personnel Management] could and should do that, but OPM has never been staffed or had that mindset to do that thing. They should be doing that in cyber and with procurement specialists. They should be going through the federal system and saying, “Here are categories we know we're going to hire over the course of the next year. Let's have an open and continuous hiring process.”

The Presidential Management Fellows (PMF) program, by the way, is a little bit like this: you apply to the PMF program in a pool. You can go to any agency, and the agency can interview and select you and bring you on board very quickly. [NB: A Feb. 20th executive order eliminated the Presidential Management Fellows program.]

We also have a lot of constraints in procurement. We had a great example of doing things uniquely within the existing infrastructure: we had billions of paper savings bonds records, in all kinds of forms and formats. Bonds were sold in different ways, they were payroll, there were different ways you could get them.

The savings bond program has been declining for years, except one day Senator Kennedy, a very influential senator from Louisiana, said, “I want to make sure we get those savings bonds records digitized.”

He gave us $50 million to digitize our savings bonds records to make them more accessible and readable. We initially estimated it would cost us $100–125 million to do the project. We initially went out and did a standard solicitation: “Hey, can someone help us with digitization?” That first effort was a failure. We did not get the kind of quality or responses that we wanted.

In the government, sometimes you take second-best because you've got a senator who's really interested in this, and he’s telling you that you've gotta move forward quickly. Well, we had a really good relationship with Senator Kennedy's office, and we said, “We're not satisfied. You need to trust us. We're going to get this right, but you need to be patient with us.”

We went out with a second solicitation. We ran a competition: companies got our data and 4-6 months to show us what digitization they could do. At the end of that period, we got an incredible proposal back — in the end, it meant we were able to digitize four billion records.

This firm put together a very small team of machine learning experts, and they came back and said, “We can do this for far less money, for higher quality and a greater speed than anyone else.” To date, we have digitized close to 4 billion records, and we have done that for less than $50 million. We haven't spent the full $50 million Senator Kennedy gave us.

One reason it worked out is that, in the Fiscal Service, we move our executives around so that they have exposure to the organization. It turned out that the executive for this program had been the head of procurement. When we didn't get a good answer to the first solicitation, he knew how to work within the existing procurement authorities and come out with a better outcome. That came out of creativity, of looking at things differently, and it came out of executives who were prepared to look at something differently.

You were the acting Secretary of the Treasury during this past transition. What was that like?

In some ways it was the highlight of my career. Just before January 20th, Treasury offboarded close to 100 political appointees: the secretary, deputy secretary, the senior-most people in the department. During these transitions, you have a career staff that remains and continues to run the organization. I started as a GS-9, and ultimately ended up at the end of my career having been able to serve as the acting secretary and deputy secretary.

I would start every meeting with the career staff acting in the senior roles by reminding them that Treasury is the most consequential bureau or agency in government. Whenever there's a crisis, people turn to Treasury. I would also tell political appointees when they came in: Treasury is where people go to have good ideas implemented, but it's also where bad ideas are stopped. Every Secretary will tell you this. In any administration, there are bad ideas, and someone needs to sometimes raise their hand and say, “That's a bad idea.” Treasury historically has played that role.