Today's guest is near and dear to my heart. It's my dad, Diego Ruiz. For the record, my dad and I recorded this in person, and we both had the same cold, which you may be able to hear. At some point, you may also hear my son in the background, which makes three generations of Ruizes on the podcast.

I didn’t just talk to my dad because he's my dad (although that’s part of it). In some ways, he’s the model Statecraft interviewee: involved in winning elections in the US and Central America, Diego also served as Executive Director of the Securities and Exchange Commission (SEC), as a senior advisor in the House of Representatives, and as Deputy Chief for Strategy and Policy at the Federal Communications Commission (FCC), managing a multidisciplinary “in-house think tank.”

In this episode, we discuss:

How to win a congressional election in Miami

What “burrowing in” to the civil service means

How to win a presidential election in communist Nicaragua

How the Sandinistas used Michael Keaton and Mike Tyson to dampen voter turnout

Why the Base Realignment and Closure Commission may be a model for DOGE

This is the first of two episodes with Diego. Enjoy!

Thanks to my colleague Beez for her judicious transcript edits.

For a printable transcript of this interview, click here:

You've had a pretty cool career. I don't think Statecraft would be what it is if I hadn't grown up in this house, hearing your war stories — let’s start with your work for Ileana Ros-Lehtinen.

Ileana is known for having been the first Latina elected to Congress in its history, and the first Cuban-American also elected to Congress. I got the chance to work as her youth director in a special election in 1989, when she was running for the seat that had been vacated by the death of Claude Pepper.

Claude Pepper was a near-mythical figure in the Congress — also known as “Red Pepper” because of his left-leaning political views. He had been elected to the Senate in 1936 before serving in the House again from Miami. When I worked on Ileana's campaign, before she succeeded Claude Pepper, the district was essentially Miami Beach, downtown Miami, Coral Gables — the heart of Miami.

That was the first special election after George H.W. Bush was elected, right?

Exactly, so there was a lot of media attention. This was mid-1989, so the focus politically was on this race, and it was playing out in the context of this new ethnic dynamic that was interesting to cover.

Gerald Richman, the Democratic candidate, made some statement early on in the campaign to the effect of “this is an American seat,” which did not resonate very favorably among Ileana's constituency. It was seen as a nasty shot fired across the bow of the emerging Cuban-American and Hispanic electorate.

The race was tense, and it was my first foray into politics. I was a 21-year-old youth director, which meant I was the guy in charge of getting out the youth vote — but more important than the youth vote itself was generating volunteers to walk precincts, hand out flyers, and staff events. We did a lot of guerrilla media tactics. I don't know if they were innovative, but they were very effective in getting a lot of attention to the race.

We did big rallies on street corners. I remember one on the corner of Lejeune and Calle Ocho, right in the heart of the Coral Gables area. We put college kids on every corner with signs: HONK IF YOU LOVE ILEANA. She came out for a few of those and waved at passers-by to motivate people, remind them the election is on Tuesday, and get some great coverage that elevated the election profile. We made the front page of USA Today, which was in its heyday back then, and I still have the clipping of that issue.

I was placed on that campaign because at the time I was working for a remarkable gentleman and a legendary figure in the conservative movement named Morton Blackwell. Morton Blackwell had been a special assistant to President Reagan who served as his liaison to conservative and religious groups. After his White House years, Blackwell started a non-profit called the Leadership Institute, whose mission was to train young conservatives for different types of political processes.

What did you learn there?

Tactical things, like how to start and run a conservative college newspaper, land a job on Capitol Hill, pass the foreign service exam, run a youth campaign. There was electoral stuff as well, and how to get a federal civil service job and burrow into the federal bureaucracy as a conservative.

“Burrow in?”

We're recording in late 2024 — the incoming Trump administration is going to fill 3-4,000 political appointments, or Schedule C jobs. If you had a Schedule C job under the previous administration, you're out of a job by the inauguration. So the way to burrow in is to transfer to a non-Schedule C job, to a federal civil service job. One of the Leadership Institute classes was about burrowing into the federal government so that you could stay on as a civil servant after a particular term.

I went to the University of Virginia for undergrad, then got hired by Morton Blackwell to be his special assistant to the President and Director of Publications. I was in charge of the newsletter, the annual report, and various other publications. Being at the leadership institute gave me the opportunity to audit every course for free — including “How to Run a Youth Campaign.”

You'd never been in electoral politics before then?

I really hadn't — but I did get bitten by the political bug in college, and became very interested in conservative ideas.

Right after college was my first chance to put them into practice. Morton connected me to Ileana Ros-Lehtinen’s campaign manager, and off I went. She won; it was terrific. That gave me the desire to work on the Hill, having seen a congressional campaign up close from the inside.

You wanted to keep going.

I wanted to see what working on Capitol Hill was like. I had made a list of all of the conservative members of Congress that I knew just from reading the Wall Street Journal and the Washington Times on a yellow legal pad. I made a big stack of my resumes, went to the Hill, and started going door to door.

You could do that back then?

Yeah, you could actually knock on the door. Sometimes, you just walked in and talked to the receptionist: “Hi, I'm dropping off my resume. Do you have any openings?” Every so often, the chief of staff might come out and give you a handshake and a once-over.

I got a call to come back and an interview for Representative Chris Cox. That was in ‘89.

Let's go back a second: In ‘89 Ros-Lehtinen won, and you had an immediate new Central American adventure.

Indeed — and I now had campaign experience: I had just come fresh off of winning an American special election of the first Hispanic elected to Congress.

Lo and behold, there was another election scheduled for early 1990 in Nicaragua, where the communist Sandinista regime was in power, backed by Cuba and the Soviet Union — but they decided to hold elections. The Central American wars were going on, the Contras were being funded by the US on and off, and the Sandinistas believed their own propaganda: They determined they were popular enough to hold elections, win them, obtain the legitimacy that comes with elections. They thought that would mean that Ronald Reagan and George Bush would leave them alone.

That is, they thought that if they held elections, Americans would have to stop funding the Contras.

Exactly. “You can't oppose a democratically elected regime.”

When they called for elections, how long had they been in power?

They took power by toppling the Somoza dictatorship in 1979, so they had been in power for nearly 10 years.

The country was just a disaster, as you might expect of any communist country. It had become the poorest country in the hemisphere, poorer even than Haiti. Granted, there was a low-intensity guerrilla war going on in the jungles, but they used the same economic playbook as Cuba did and ran the economy into the ground. People were suffering acutely while the Sandinistas persecuted their political opponents, threw people in jail, tortured people, etc.

So they call an election, and the opposition candidate that emerges is a woman by the name of Violeta Chamorro. Chamorro is the owner of the only independent newspaper in the country, La Prensa, and the wife of Pedro Joaquin Chamorro, publisher and editor of La Prensa, who was martyred during the Somoza years. She comes from a very well known family, is very well known herself, and has a sterling reputation for civic engagement and democratic principles.

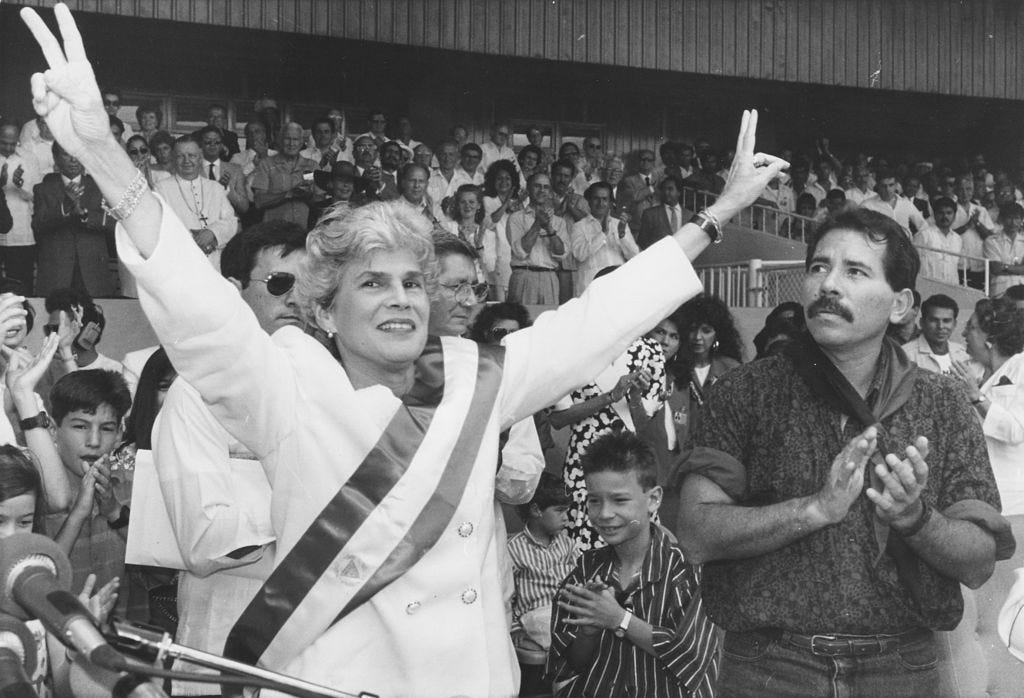

Violeta Chamorro at her swearing-in, as outgoing dictator Daniel Ortega looks on.

And her husband had been gunned down by the previous regime?

Yes. She became the consensus candidate of all of the parties that opposed the Sandinistas. It was a pretty broad array of 14 parties, from free market conservative parties to, actually, the communist party of Nicaragua. You wouldn't think it, but the Nicaraguan communist party was not aligned with the Sandinistas.

As you would expect in a totalitarian communist state, the opposition candidate had no resources. She had roadblocks thrown in her way at every possible step by the governing Sandinista regime.

Chamorro asked for help in ‘89 and got help from a group of Republican US Congressmen who were very interested in Central American freedom and in Nicaragua specifically. They helped her raise some money among their US donors.

The congressmen also hired a small-but-hardy team of political campaign consultants to assist the Chamorro campaign with what little resources they had (because they just didn’t have the resources to run a normal campaign). Whatever they tried to get would be impounded by the Sandinistas. I remember fax machines being held up at customs by the Sandinistas — they sat in a box in some warehouse throughout the campaign because we just couldn't get them. The Sandinistas controlled absolutely everything.

There were two other newspapers; they controlled both of those. We did have a newspaper and it was by far the most well-regarded, but I think there were two TV stations in the whole country, both government-owned, along with most radio stations. There were some low-wattage radio stations that were somewhat free.

There were very few resources to run any kind of campaign, let alone a modern electoral campaign, so US congressman David Dreier of Covina, California got involved. He later became the longtime chairman of the Rules Committee when the GOP took over in 1994. He was an internationalist, pro-free-trade, and pro-muscular American diplomacy. He led the other congressmen in pulling together some assistance for Chamorro and hired a consultant by the name of Tony Marsh, who in turn hired me.

I got hired simply because they needed a junior member of this three-man team. They needed someone who spoke Spanish and had campaign experience. I raised my hand as high as I could get it and I got taken up. Off we went to Nicaragua.

How many people went to Nicaragua?

Three people went to Nicaragua, but only two of us stayed there the whole time. Tony would go back and forth, but he just set up the team and left us running. We were cheek by jowl with Violeta Chamorro. I traveled with her to 13 of the 16 provinces of Nicaragua.

Did you have a budget to draw on?

No. We stayed in the Intercontinental Hotel for the first week. It was where all the foreign journalists stayed, and it was maybe the only hotel in the city; everything else had been destroyed by the 1972 earthquake that destroyed downtown Managua. Somoza had stolen all the foreign assistance, so Managua was never rebuilt. I eventually stayed with a local family. We couldn’t afford to stay the whole campaign at the Intercontinental, so we eventually got rooms with a local family.

We couldn't do television, radio, or direct mail because there were literally no addresses in Managua at the time. The streets had no names — they had been destroyed. If you wanted to send a letter, you would write on the envelope, “Three streets down from the Citgo sign and one street towards the lake, pink house.” That was it. And the letter somehow got there, as far as you knew.

But you couldn't do a mass campaign.

You could certainly not do any sort of direct mail like you could in the US. So we did rallies.

We just mobilized the candidates — Violeta and her vice presidential pick, Virgilio Godoy — with one or the other, we traveled everywhere. We would drive out for hours, sometimes almost a full day of driving out from Managua, and hold rallies in the town square.

And they gave the stump speech?

They gave the stump speech. Some sort of a makeshift stage would be set up. You’d have your food vendors on the edges of the plaza and people would mobilize. The campaign did a great job of mobilizing people. People were losing their fear, and they were turning out. After 10 years, they were so ready for change.

But even so, the Sandinistas did everything they could to stymie that. They would have these mobs made up of basically Sandinista thugs (they called them the turbas divinas – the divine mobs) that would stand on the edge of the plaza, throw rocks, beat up people, throw this itching powder that they made — crazy, crazy stuff from some local plant they called pica pica. It means itch itch in Spanish. They would toss this powder up in the air. I imagine they had to kind of figure out which way the wind was blowing so that it wouldn't blow back on them, but if it got into your eyes or on your skin, it would just create this awful rash.

Did you get the rash?

I did not, mercifully. But I was almost lobotomized by a rock the size of a small marsupial, as I wrote in my journal at the time.

I was walking with the crowd from the campaign towards one of these town squares for a rally. I got left a little behind because I was changing the film on my camera. I’d stopped in the street to change the roll, when all of a sudden, I heard behind me, “Gringo de mierda!” I turned around just in time to see this very large rock coming right at my head, and I ducked at the last minute. It sailed right over me, but it had been heading hard for the back of my head.

It was things like that. Every day, our phones were tapped. I remember coming home to my room in this family's very humble home, and there were pages from my journal missing. I’ve never changed so many tires in my life. Every time we went out, they would throw those little tacks that always point up — the kind you see them throw in the road in spy movies, the five- or seven-pointed ones. In Spanish, they’re called Miguelitos, “little Michaels.” I’ve since learned they’re called “caltrops” in English – who knew? They would toss them in our way all the time. We’d always carry two or three spare tires in our SUVs.

There was all kinds of interference with the campaign, but was there also a big international observing presence separate from you guys? Were there limits on how much the Sandinistas could subvert the elections?

Kind of. They actually did not think they needed to steal the election. They would have tried harder had they thought it would be closer. There were polls at the time, but not very many, and the polls showed the Sandinistas winning in a walk.

Really?

What becomes evident after the fact is that in a communist state, people lie to the pollster. They're not about to tell the pollster, who’s some random guy — maybe a gringo — they don't know you. They're not going to tell you what they're going to do. In the end, we won by 15 points. It was bigger than most American landslides that I can think of — 55% to 41%.

It's hilarious to look back on some of the things that the Sandinistas did, within the bounds of a relatively free election, to stymie us, and to see how much they got away with. For instance: the campaign officially had to end a couple days before election day. Each of the two campaigns held one last enormous rally in Managua. We went first, and the Sandinistas went the second night. These were nighttime rallies where the campaigns tried to mobilize everyone with a last call to action before election day.

The day of our rally, the Sandinista government decided to schedule union meetings of every type of transport and vehicle: the railroad union, the bus drivers union, the truck drivers union were suddenly called to very important mandatory meetings with their vehicles.

All of those vehicles were taken out of commission?

They called employee meetings at every major place of employment: factories, big land holdings, and collective farms. They made it as difficult as possible for our people to mobilize.

The coup de grâce was on the two television broadcast stations that transmitted nationwide, which of course were run by the Sandinistas. On one of them, they scheduled the global premiere of the very first Batman movie with Michael Keaton that came out in ‘89. They bought the rights from Hollywood to premiere it on their dinky, grainy TV station — just so people stayed home and watched Batman, of course.

And on the other station, they buy the live network rights to the Mike Tyson vs. Buster Douglas fight in Tokyo. They didn’t know this, but it would be the very first time Mike Tyson lost. And they put that on the other TV station.

So you've got options.

And meanwhile, we're trying to get people to our rally, which actually was a great rally. I'm sure it would have been even better had we not had disloyal opposition.

On election day, I was assigned to a group of Polish election observers that had come to keep an eye on the election. They were members of the Solidarity Party in Poland. They had just won.

For some historical context, the election was on February 25th, 1990. While the campaign was going on, the Berlin Wall came down. In fact, Mrs. Chamorro took a very quick trip to Europe to generate support and attention for the election, and also to do some press-worthy events at the Berlin Wall.

She actually brought back a piece of the Berlin Wall, which we then used in every single campaign stop for the rest of the campaign in Nicaragua — to link that election to what was happening globally. We were trying to convey that Nicaragua’s communist government was the next wall to fall. That was brilliant guerrilla marketing and electioneering because we were able to use visible events that were taking place around us at that time to draw attention to our little piece of the struggle. We motivated our voters by linking the ideas that undergirded the movement towards freedom in both places at the same time.

What else did she run on? What was in the stump speech?

As I recall, it was a freedom speech. Whatever romantic idea people might have had about the Sandinistas was long gone by then. They were corrupt, they were thugs, they were violent, they threw people in jail, they tortured, they were not democratic. They got a lot of slack early on because they overthrew a right-wing dictator. Latin America has this perennial search for the next Fidel Castro and the next Cuban revolution. And the promise that that revolution held, at least for some people, was romantic. The Clash had an album called Sandinista!

Is it good?

It wasn't as good as the earlier stuff, no. I had a roommate who had a big poster of that album on his wall after I worked in Nicaragua, and I was forever at war with him to get him to take it down, and he never did. But I did manage to get him to move it from the common area into his own bedroom, so I claim that as a victory.

Anyway, Chamorro’s stump speech was a straightforward pro-freedom speech. People were hurting. Many people had lost family, either in the revolution against Somoza or in the conflict with the Contras. People had been arrested.

I remember in one of the rallies, Virgilio Godoy, the vice presidential candidate, was speaking. Lovely guy. I hosted him a few years later in California when he visited while in office. He was on his way up to the stage to speak, and we started getting pelted by the Sandinista mob on the edge of the plaza.

Thankfully in this instance, they were throwing eggs. He got hit with an egg to the side of the head. He got up on the platform to speak, and I remember him saying, “Porque ellos tienen los huevos podridos!” Because their eggs are rotten. Essentially, I may have been pelted with a rotten egg, but their eggs are rotten. People loved it.

There was not much love for the Sandinistas at all. If you were on the inside, if you were a member of the party, if you held a government position, then things were cushier. But it was a classic tale of communist regimes everywhere: the party was meant to be the vanguard of the revolution, but it ended up being the most corrupt and self-seeking of the whole bunch.

Take us back to election day.

On election night, we were in the bunker, this big, covered space in Managua. We start getting some of the initial returns, and the returns look incredible.

What's coming in first, Managua or the rural regions?

I would think it was Managua, but I really don't remember. Here's my main memory from that evening: Jimmy Carter was there, nine or ten years after he left office.

By this time, the Carter Center, his vehicle for promoting democracy and observing elections, was up and running. My recollection is that this was the first big election that he attended in person.

We start hearing gossip. Nicaragua is, at the end of the day, a small country run by a small number of families. In fact, the Chamorro family itself had people in the Sandinistas, as well as in the opposition. Our top people knew the Sandinistas’ top people very, very well — so there's some amount of communication and gossip getting across from one bunker to the other.

Through personal backchannels.

We start hearing that Jimmy Carter is doing a bit of shuttle diplomacy. He's over in the other bunker with Daniel Ortega, who was president of Nicaragua at the time — and he’s president again today, sadly. This is how circular things are in Latin America and in Nicaragua, specifically.

Through that shuttle diplomacy, Carter got Violeta Chamorro to agree to let the Sandinistas keep control of the military and the intelligence apparatus, in exchange for them willingly giving up and transferring power to her. That was the deal Carter cut.

It gave all of us a bad taste in our mouth. And to this day, I think it was a stain on his record. I think he felt that he was doing the right thing, because he was bringing about a peaceful transition — and that there would not have been a President Chamorro without that deal. There might have been violence, or at the very least, the Sandinistas would have stolen the election and refused to step down.

But in convincing Chamorro to accept those terms, Carter basically condemned her presidency from day one. It’s impossible to restore democracy and start to clean up the country when the Sandinistas have a gun to your head, literally — in the form of the armed forces, the intelligence services, and the security services. So she governed as best as she could for four years with a viper in her bosom.

Of course they held on to all of their ill-gotten gains. They referred to the spree of thievery that they orchestrated in their last few days in power as the piñata. Everyone refers to that time period as the piñata because they just got their goodies when they had the chance — they shook down everything that generated income and pocketed it as quickly as they could, because they were leaving power.

The Sandinistas held onto everything: the best properties, the best houses, factories, and farms. Nicaragua has never really emerged from that level of corruption and poverty.

And after that you end up back on Capitol Hill, stateside.

Yes. Pretty soon after getting back from Nicaragua, I landed a job with a very bright freshman member of the House named Chris Cox from Newport Beach, California. Wonderful district. I started out in Washington, but later ran his district office and — let me tell you — it was the best job I ever had, being on the beach in Newport Beach. And at the time, I believe it was the most Republican district in the country.

Cox had just come out of the Reagan White House, where he had been counsel to President Reagan in the White House counsel's office. He won a very crowded Republican primary because of the great experience he had in Washington and the iconic figures he brought out to campaign for him, including Oliver North and Robert Bork, at a time when those two names were household names. He won the primary and the election hands-down, and I got hired shortly thereafter.

One issue that stands out from that time, because it was groundbreaking, and because of my office's particular involvement in it: the base closing process, or the base closure commission.

The BRAC [Base Realignment And Closure] commission.

Yes. This was a brainchild of Dick Armey from Texas, who later became House Majority Leader when Republicans took over the House in ‘94.

He was basically Newt Gingrich's right-hand guy. When Newt became Speaker, Dick Armey became Majority Leader. He was an economist, very folksy, very smart, conservative, free market, and just a great guy, and he came in with this great idea for closing down unneeded military bases. There were a lot of these. But once a base was established in some Congressman's district, typically there was no way to shut it down.

It's somebody's pet project.

That member will do anything to protect it. Everyone has something they want, so the natural horse-trading and log-rolling process would take over, and no base ever got closed. Besides, the Department of Defense (DOD) couldn’t recommend it for closure either, because they couldn’t afford to cheese off that member of the Congress.

They’d make an enemy for the rest of the budget process.

Forget about it if it's a powerful member of Congress, but even if it's some backbencher, why go through the grief? What's in it for DOD? You have a million other things you care about more than that.

This is a classic federal-waste-in-miniature story, where the benefits of keeping it are very concentrated and the harms are diffuse, so one person can always hang onto it, and it never rises to the level of priority sufficient to actually gut it. And this stuff piles up.

And there are no incentives. The incentives are simply not aligned for anyone to come in and do what makes sense and save money. The incentives are aligned in the exact opposite direction.

Dick Armey’s revolutionary idea was to take it out of the hands of the Congress and create this commission. I can't remember how it was picked, but it was bipartisan, both parties got to pick members, and the commission had the authority to look at all of our bases.

Did the commission survey bases from every service branch in the US and abroad?

It was just the US, so it avoided some of the thornier issues of foreign alliances and force projection and things of that sort. There were plenty of US bases to keep them busy.

They had months of hearings where the entire commission sat and heard testimony from the military. They actually did ask the branches to tell them when they needed bases, ask local communities when they could do without them, etc. At the end of that process, they came out with a recommended list of closures.

The innovation here was that Congress had to vote the entire list of recommendations up or down — they could not amend it. The process was, “You accept the entire list or you reject the entire list. You cannot save your own base. There will be no opportunity in the process. There's no pulling just yours out of the fire.” There were several [five] rounds of the BRAC over the years, but this was the first round.

[NB: BRAC established a mechanism of silent approval.]

I think it was a brilliant idea. Dick Armey got it approved when he himself was a backbencher. He somehow got it through the process. Kudos to him for doing that.

But my piece of this story is that in Chris Cox's district, we had Marine Corps bases that ended up on the potential chopping block: Marine Corps Air Station El Toro, which was a jet fighter base, and Marine Corps Air Station Tustin in the city of Tustin, a big piece of real estate in the middle of Orange County with two enormous wooden hangars, from when the military fielded a fleet of helium blimps.

Hangar No. 2 at Tustin, one of the largest free-standing wooden structures in the world.

They were blimp hangars?

They were blimp hangars. Enormous. They burned down, tragically, just a few years ago. They were the largest freestanding wooden structures in the world. Like the picture in your head of a hangar — that's what they look like, but 10 times bigger than whatever you're thinking. Think of the Led Zeppelin I cover.

How do you get the blimp in there?

I guess you fly it very low.

So that’s an obvious base for closure.

It's an obvious one for closure. Now, here's where I thought Chris Cox was wonderful, and a real statesman: Any other congressman would have said, “No. You cannot close down my base. The…vital importance… of our helium blimp fleet… is an underappreciated strategic priority for national defense, and it creates hundreds of jobs in my district, and over my dead body will you close it.” And instead, to his great credit, Chris said, “Please close my base. There's no sense in this remaining open. There's many better uses for it.”

And the process for doing so was one that everyone could be comfortable with because it involved plenty of analysis. The El Toro base wasn’t as clear-cut a case, but it was in a highly urbanized, very residential area, and it had Marine Corps F-18 jets taking off and landing and making a lot of noise. It didn't sit easily with the interests of the community around it. The Marines were increasingly less comfortable there.

I'm guessing there's lots of places for the Marines on the California coast.

Exactly right. They're not wanting for bases. So Chris ends up being the first member of Congress to ever say, “Yeah, close my bases.”

Did he talk to the BRAC, or was it just the vote?

He actually testified before the Base Closure Commission and said, at least in the case of Tustin, that it was clearly a much better use of that land and those resources to close them and turn them over to the private economy, which is what I think ended up happening.

So that was a fun policy-done-right story. I've seen a lot of criticism of the Department of Government Efficiency (DOGE) for being a blue ribbon commission. To do real government reform, they say, you need something with teeth — not just something that makes recommendations.

But in the case of the BRAC, you had a blue ribbon commission with a mechanism that helps you operationalize those recommendations. I wonder if that’s a useful model for the DOGE.

It could be. Clearly, the jury is not only out on the DOGE, it hasn't even been impaneled yet. We'll see what they come up with, but I believe in processes that align people's incentives to do the right thing, or removes incentives to do the wrong thing. BRAC revoked the Congressmembers’ ability to stand in the way of something that it was painfully obvious needed to be done. To the extent you could do some similar mechanism for the DOGE, or maybe some subset of their recommendations, that's not a bad thing to explore. I would imagine that will require an act of Congress. Maybe you can package them in a way that makes it inevitable that they get approved as a package, without the ability to pick and choose.

You know, a similar model is fast track authority for the president to negotiate trade agreements. The Congress has to authorize fast track authority for the president, which empowers the president to negotiate the treaty, say USMCA, NAFTA's successor, and return to the Congress for approval on an up and down vote, without the ability to amend it.

Now, there are many reasons for that model: it's hard to negotiate with a foreign power when you have multiple negotiators and goals.

It's funny — conservatives today often criticize that omnibus model in the cases of appropriations bills, the must-pass bills where you stuff everything into them, because Congress didn't get a chance to actually pick apart the different issues at play. It's not an up-or-down vote on one kind of reform; it's everything that everybody wants to pass that year.

Right, and you're packaging together literally 100% of a Congressman's responsibilities in office into one bill: Yes or no. Congress has the power of the purse and we're stuffing one purse full of everything. And you get to vote it up or down with little to no time to actually scrutinize what's in it.

Theoretically, the value of an up-or-down vote is maximized on things where you could reasonably have a yes or no opinion on that whole package.

Exactly. Also, the BRAC had a well-thought-out, transparent process that took place over months.

Everybody saw what was going into it.

Everyone saw it and everyone had a chance to input. There wasn't that feeling that surrounds an omnibus bill, where it got put together in a smoke-filled room on a Tuesday, and we’re voting on Wednesday morning.