When the Soviet Union fell in 1991, hundreds of tons of nuclear materials were suddenly unsecured. The new, fragile Russian government had no ability or desire to claim facilities in formerly Soviet states like Georgia and Kazakhstan, and it could no longer pay nuclear plant workers. Operatives from Iran, Iraq, Libya, and North Korea offered cash to purchase uranium and hire nuclear physicists. If not for urgent action by American diplomats and their foreign partners, a rogue state or terrorist group could have acquired a nuclear weapon.

What You’ll Learn

How did the US secure dangerous nuclear materials?

Why didn’t the Department of Energy want the US to acquire them?

Why shouldn’t you bring bourbon to Soviet functionaries?

Today’s interviewee can answer these questions better than anyone. As his DARPA biography outlines, Andy Weber led the removal of weapons-grade uranium from Kazakhstan and Georgia, and nuclear-capable MiG-29 aircraft from Moldova, to reduce biological weapons threats, and to destroy Libyan and Syrian chemical weapons stockpiles. He has spent thirty years in the US government, including more than five years as President Obama's Assistant Secretary of Defense for Nuclear, Chemical and Biological Defense Programs. In addition, he coordinated US leadership of the international Ebola response for the Department of State.

For a printable transcript of this interview, click here:

After the fall of the Soviet Union, you were trying to secure nuclear materials in those former Soviet states. Where were you getting your intelligence?

We had access to all source intelligence, ranging from SIGINT (signals intelligence) to HUMINT (human intelligence), and open source intelligence. Then there was another form of intelligence that I called “GOINT” or “ASKINT.” That's when you get on the plane and you go to the site, or talk to the government, or visit the facility and talk to the scientists. After the Soviet Union collapsed, the Nunn-Lugar Cooperative Threat Reduction program gave us a reason to be there. Being on the ground was our best source of information. The amount of non-espionage intelligence that we were able to gather, just in the course of our business, was truly extraordinary.

How do you process all that information? Did you wake up and get a briefing?

It depended on the level I was serving at. When I was at the Pentagon, we would get our morning take of intelligence and we would read it. When I was more senior, serving at the Assistant Secretary of Defense level, I actually had a briefer assigned to me who would come in several times a week, with the analysts who wrote the more in-depth reports, to brief me on different intelligence topics.

But I was an avid consumer of intelligence. I read the so-called raw intelligence: the signals, intelligence reports, the CIA human reports. When you put it all together, it gave you a good picture. There were times when specific intelligence led us to action. Some of the projects I was originally involved in were based on very sensitive intelligence.

How did your intuition for what to act on change over time?

I had a lot of interaction with individuals, and that gave me a good sense of who was telling me the truth, and who was just blowing smoke. The ability to size up people and know whether or not to trust them was an invaluable skill for reading intelligence.

You learn to evaluate the sourcing. Usually in human intelligence, there's a source description that describes not just the reliability of the source, but the chain in which he received the information, whether it was information that he had direct access to, or whether he was talking to third parties or more indirectly. Understanding that was very important.

I think there's a tendency to overvalue things based on the classification. Just because something is classified or top secret doesn't mean it's true or correct. Especially in crisis situations, you are just flooded with information, and a lot of it is bad information. In a crisis, the collection is amplified, and anybody who thinks they have something to add will send in a report. The quality filter is lower.

But when I served as Assistant Secretary of Defense, I had a fantastic relationship with my briefers from the CIA, the NSA, and the DIA, and I did something that not all policymakers do. Oftentimes, I would go out to them and see them on their turf, whether it was up at Fort Meade, or at Langley, or down in Charlottesville, where we had a DIA group focused on weapons of mass destruction issues. I got to know them too. It was really important, as a good consumer, to have a relationship with your intelligence analysts.

Why did that help?

I just learned so much. The expertise these people have is not written down. So much of it is in their heads, because an intelligence analyst has the luxury of spending all of their time narrowly focused on one thing. They read everything imaginable about it, and, although they're trained not to give policy recommendations, what’s in their heads can certainly help define options and allow policymakers to bounce ideas off of them.

You were First Secretary at the American embassy in Almaty, Kazakhstan, when you received a tip about uranium sitting at a warehouse somewhere. How did that happen?

It was a process of quite a few months. Slava was my car mechanic, a fixer kind of person, and occasionally my driver. He asked me one day if I'd be interested in buying some uranium.

He hadn't suggested this kind of transaction before?

No. And this was at a time when the Soviet Union had collapsed, so there were all kinds of scams, crazy stories about suitcase nuclear weapons. Oftentimes on the black market, they would offer actual plutonium, or what they’d claim was highly enriched uranium for sale.

But it was very small quantities, much less than a gram, and they would say, “This is just a sample, but there's much more behind it if you're interested.” We would actually observe these scams through signals intelligence and other intelligence when they were targeting countries like Libya and Iran, who they knew were interested in buying these things.

Most of these stories didn't check out, but I told him that I would be interested in learning more.

Did the people doing the selling have access to nuclear facilities?

Sometimes, as in this specific case, which ended up being called Project Sapphire. My initial discussion with Slava led to an introduction with the director of a factory in east Kazakhstan, at Ust’-Kamenogorsk. He was a director of the Ulba Metallurgical Factory named Vitaly Mette, and he had direct access and knowledge of everything that was going on at his factory. It took me many months, and a lot of developing personal rapport and trust, before I got any detailed or usable information about potential uranium at his facility.

What did that process look like? Were you taking him to dinner?

There were a lot of dinners, a lot of vodka. Once, I made the mistake of giving him a gift of a bottle of Wild Turkey during one of my visits up north to his apartment in Ust'-Kamenogorsk, and he proceeded to say thank you, opened it, and immediately said, “Okay, now we’ll finish this together.”

But the time I remember best is, after a meeting in Almaty, which is very far from Ust'-Kamenogorsk, we talked about hunting. He knew I was a hunter, and it was maybe late October. He said, “Why don't you come up to Ust'-Kamenogorsk? I'll take you hunting.” I said sure.

One weekend, I went up there on a hunting trip with him. At the base camp, we did naked banya with his hunting guide friends. That was really important in eventually uncovering what was at his factory.

It was first snow early in the morning when we went on the hunt. I actually shot a moose on that trip. A KNB lieutenant colonel fell asleep in his Jeep, trying to stay warm. He woke up, and there was an elk that had walked right past the Jeep, and he pulled out his nine-millimeter Makarov pistol and shot the elk.

It was a lot of drinking, and the banya, and salted dried fish and vodka. We really bonded. But he didn't tell me any specifics about the uranium. I said, “Look, the United States government might be interested in purchasing this, but we need to know the details. What's the enrichment level?” Because we knew his plant was producing low-enriched uranium fuel pellets.

Over time I pressed him. And then, this is something that I play over in my head, like a video, I remember it as if it was yesterday. Slava came one afternoon to the US embassy in the old capital of Almaty. It's since moved up north to Astana. He said, “Andy, somebody wants to meet you,” and I said okay, sure.

We left the embassy, hopped in his Soviet vintage military Jeep, and he drove me to the outskirts of town, to a small company called Bars, which means snow leopard. They were selling night vision goggles, basically military equipment, to sportsmen and hunters. I went up into this apartment building where they had their office, and met Colonel Korbator, who was a former KGB border guard. We were all talking, a bunch of guys, and then he said, “Andy, let's take a walk.”

It was snowing that day. We went out into the courtyard and he said, “Andy, I have a message for you from Vitaly Mette,” the factory director. We were walking, and he discreetly passed me a very small piece of paper, folded in half.

I took it out of his hand and I kept walking, and I looked at it, and I gulped, and put it back in my pocket. It said “600 kg, U-235, 90%.” That's weapons-grade, highly enriched uranium (HEU), and 600 kilograms is enough for perhaps several dozen nuclear weapons. I was just absolutely shocked because our intelligence didn't indicate that there was any HEU at this factory. There was a lot of skepticism when I reported that back to Washington.

Did you believe it?

Right off the bat, I did. And honestly, I took a risk in believing it, but it was because I trusted Vitaly. By then, I got to size him up, know him pretty well, and he seemed like a straight shooter. So I reported that back to Washington and this led to an effort on my part, with guidance from Washington, to try to move this from what had the feel of a black market deal into a secret government-to-government channel.

I was able to do that over time. President Clinton invited President Nazarbayev to visit Washington, and we had a private meeting in President Nazarbayev's bedroom where he was staying in Blair House.

How did you convince Washington to push for a meeting between the Kazakh president and our president?

Well, I was a young man then, 33 years old. I worked for an extraordinarily talented ambassador, William Courtney. We were in constant communication about this, and he was very supportive. I was lucky in that respect. Together, frankly, we went out on a limb with this whole concept of even considering that the US government would purchase this material, because this is something we had never done. It seemed like the right approach to us, but it took Washington a while to make that decision. In fact, there was a lot of opposition to bringing foreign origin enriched uranium into the United States.

Where did the opposition come from?

Mostly from the Department of Energy and the Secretary of Energy, on the grounds that it was a risk or a bad precedent. There were a lot of reasons. The main argument was that we would somehow create a market for this type of material.

Like with paying ransoms for kidnapping?

Yeah, but my feeling was: boy, if there are people selling this, we want them to come to the United States government first.

We’d like to be the buyer of first resort?

Exactly.

One of our requests to their president was to arrange for me and a technical expert to visit this facility and verify that highly enriched uranium was there. He turned to a general who was Chairman of the KNB and said, “Make this happen.” So in March of 1994, Washington sent out a technical expert named Elwood Gift from Oak Ridge National Laboratory.

Would you have been able to access the site without a formal channel to the Kazakh government?

Well, on my hunting trip, Mette had arranged for his staff to give me a windshield tour of the plant, before my flight back to Almaty. But I couldn’t really learn anything by just looking at buildings. I think it would've been very, very hard to verify the quantity and quality of the uranium without cooperating with the government. This was probably one of the biggest secrets that the government of Kazakhstan had.

It's only in the movies that somebody would break into a facility and take samples. That just doesn't happen. But we still did it secretly, because that's how they wanted to do it, and because we felt that the best security of this at-risk material was the fact that very few people knew it was there.

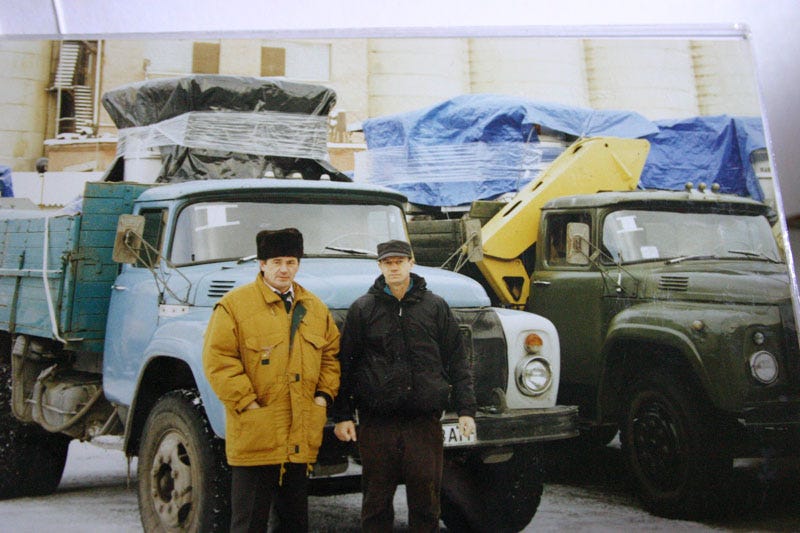

Elwood and I were escorted up to Ust'-Kamenogorsk by a Lieutenant Colonel from the KNB who flew with us in an Antonov An-12, which is a small turboprop. We had dinner with Vitaly and his team. We spent the whole next day going through the factory, and he showed us the warehouse-like area where the HEU was.

It was protected by a good padlock, is what we reported back to Washington. It was like one of those Civil War, antique shop-era padlocks. There was one female guard, armed with a Makarov pistol. Vitaly Mette had the key brought, unlocked the padlock, and we entered this large room with a platform on the floor. It was a plywood on cinder blocks kind of situation. There were different sizes and shapes of stainless steel buckets, intentionally spread out for criticality safety, on this platform.

[The uranium had been prepared for a secret submarine fuel project, which had been canceled in the 1980s. The highly enriched uranium was left behind.]

We randomly took samples from different buckets. We'd say, “We want to open that one,” and they were very cooperative. We were able to take some samples and send them back to Washington. We also did assays on-site, and were able to verify the quantity of material and the enrichment level. Further analysis was done when the samples were shipped back to laboratories in the United States.

What did the interactions between you and the ambassador and DOE look like?

It's mostly restricted cable traffic back and forth with the State Department, Defense Department, CIA and Department of Energy. There were NSC meetings held on this once that verification went back to Washington. The ambassador's cable said, “...and it's protected by a good padlock.” That set off alarms in Washington in early March. It took many, many months before we actually had a team come to Kazakhstan to package the material and secretly ship it back to the United States. They arrived in October, and then left right before Thanksgiving in November.

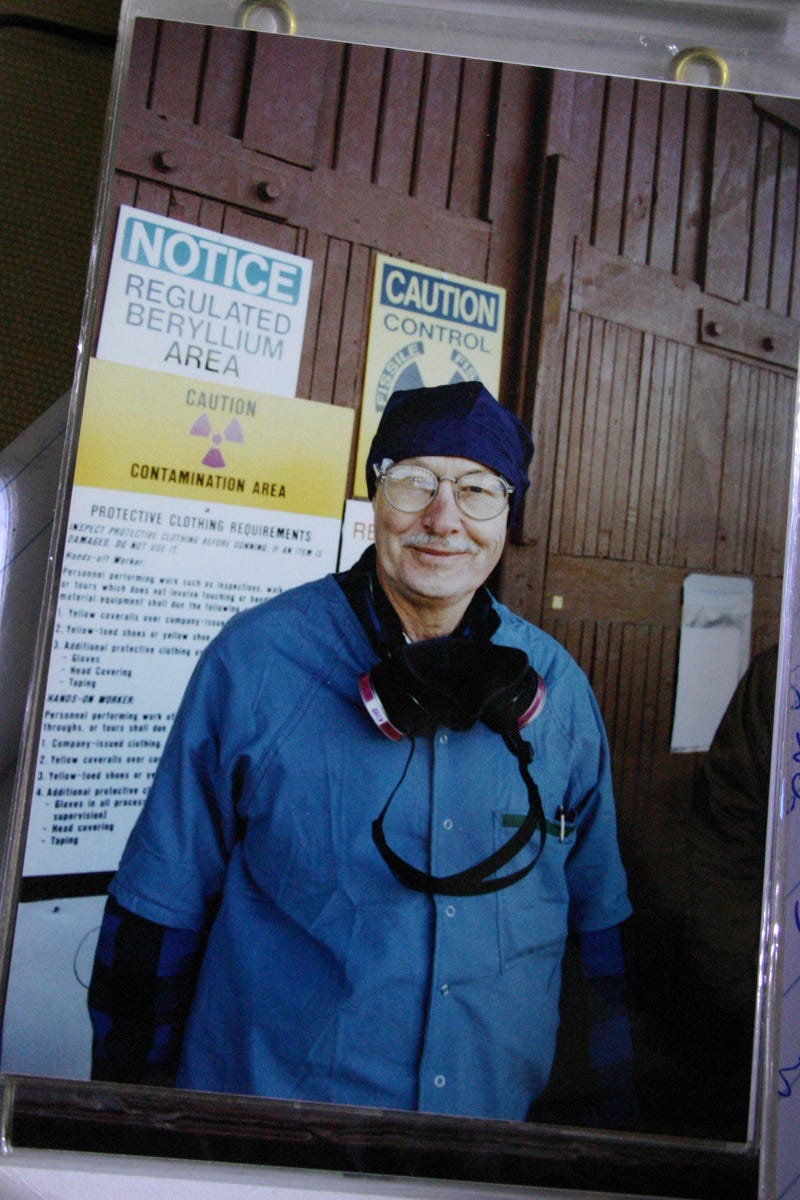

[Details of the packing process have been documented in the Sydney Morning Herald: “Each day, they left their hotel before dawn and returned after dark, spending 12 hours packing the uranium into special containers suitable for flying. There were seven types of uranium-bearing materials in the warehouse, much of it laced with toxic beryllium. Altogether, the team discovered 1032 containers in the warehouse. Each had to be unpacked, examined and repacked into milk carton-sized cans that were inserted into 448 shipping containers – 55-gallon drums with foam inserts – for the flight.”]

Where did the uranium end up?

We packaged it in Department of Transportation approved containers for transporting fissile material and flew it back on a C-5 Galaxy, the military cargo aircraft. That was, at the time, the longest C-5 flight ever. It was flown back with three, perhaps four aerial refuelings en route. The planes didn't land in Europe, they just went all the way straight back to the United States over water, and they landed at Dover Air Force Base in Delaware. They were met by a secure ground transport convoy and the material was taken to Oak Ridge, Tennessee to the Y-12 plant, and there it was secured.

Once it was behind the fence, there were press conferences in Almaty and at the Pentagon in Washington, announcing the successful partnership between our governments. And the material was eventually blended down to low enriched uranium and used for the nuclear power industry.

So that uranium got turned into cheap American electricity.

Yeah, I don't know how cheap, but sure. There was a catchphrase for the bigger HEU purchase agreement, Megatons to Megawatts.

What would've happened to your career if it was a false alarm?

I mean, I could've recovered, but it certainly would've caused reputational damage. But I thought this was probably the most important issue in Kazakhstan at the time. They had inherited, on their territory, well over a thousand nuclear warheads. Those were still on military bases under Russian control.

The world's biggest biological weapons factory was located in Kazakhstan, and they were actually at a reactor site on the Caspian Sea. There were, we learned later, three tons of plutonium in spent fuel from a fast breeder reactor. That led to a multi-year project to securely package that material and move it by rail across the country to a site in Semipalatinsk, Kazakhstan for more secure dry storage.

What’s your lesson about the value and the skill of building personal relationships in these environments?

Well, individuals matter. History doesn't just happen. I've been held up as the example for this project, but there was a massive team involved. Everything you do in government, perhaps unlike academia, is a team sport.

One piece of advice I could give to young people starting out in government service is: don't sit at your desk and have lunch. Spend time getting to know the people that you have to work with. You get stuff done by having that network. My whole career really was about networking, whether it was in my overseas interactions or back in Washington inside the Pentagon.

You've been at State and DOD, two very different institutions. What have the pain points been?

The pain points for me have always been my sense of urgency vs. the bureaucratic pace. Things are complicated, and it always takes longer than you'd expect. I learned about the 600 kilograms of highly enriched uranium in December, and it wasn't until the following October that the team and packaging materials arrived in Kazakhstan. Can you imagine?

The slowness was very frustrating. It was a big complicated operation that required training and a lot of specialized preparation. But, when there was focus and high level leadership – in this case Bill Perry was Secretary of Defense, Ash Carter was Assistant Secretary of Defense and Jeff Starr was a senior advisor to them who worked on this full-time – they really drove Washington to make this happen. Sometimes it takes that high-level push to really unblock the bureaucracy.

What's the source of that slowness?

It's process, it's decision making, it's overthinking things. Countless NSC meetings on so many topics. The project to remove and destroy serious chemical weapons is a good example of that. I had a reputation for not letting go of issues that I care about. I get very passionate and almost obsessed and, I don't know if that's always good, but it certainly is in entrepreneurial policy making.

In fact, I love that word, entrepreneurial. I remember we were with colleagues from the National Security Council staff and from the State Department, briefing on a program that had successfully interdicted Iran's attempts to gain access to pathogens, technologies, and the expertise of scientists at a bioweapons institute in Siberia called the Vector Research Center for Virology. It's one of the two places in the world that has a WHO-authorized repository of smallpox virus. The other one is CDC in Atlanta.

We learned about it from very sensitive signals intelligence. The normal thing at the time, in a situation like that, would be to dumb down the intelligence and démarche [formally solicit] the government of Russia and ask them to do something about it. We’d call them démarchemallows. But that's not good, because you risk compromising intelligence. At that time, Moscow was a very weak government, not in control of things around the country.

So we went to the source of the problem; not to some Ministry of Foreign Affairs office in Moscow. Instead we went out to Siberia to negotiate with the director, a guy named Lev Sandakhchiev. He cared mostly about being able to pay the people on his staff. I had gotten to know him very well. He had visited the United States, and then I had made multiple trips to his facility in Siberia and met him in Moscow a few times. I had come to trust him, and I learned a lot from him about the Soviet biological weapons program.

But I said to him, “The Iranians are bad actors. They're seeking biological weapons capabilities from you, right? If you agree to break off your relationship with Iran, we will work with you. We will fund joint peaceful research with your scientists. We will help improve the security of your pathogen collection.”

For about $3 million in assistance, we were able to win his agreement to break off contact with the Iranians, and we were able to verify that with intelligence. It worked, but it was creative and different, and not something that had been done before.

It was a courageous thing for him to do. There are a lot of spineless people in that system, because to survive you had to not take risks. He was going against his government policy, because they were encouraging his work with the Iranians. Russia had a good relationship with Iran – still does. But he did what was in the best interests of his institute and the people that depended on him.

We briefed the WMD Commission on how we had successfully interdicted this Iranian attempt to exploit the vector laboratory. And Congressman Deutsch asked, “Well, what is it about this? We've been briefed on 99 government programs that aren't working. What is it about this one that's working?”

Congressman McCurdy from Oklahoma answered, “What you have here, by definition, you can't institutionalize. What you have here is entrepreneurs in government who are making this happen, almost in spite of this system. So there's not some formula here that can scale up.” And I'd never thought about it that way, but I think it was really true.

You’ve worked on a bunch of individual cases. How much are your lessons relevant for more bureaucratic, process-oriented parts of the US government?

I've been on all sides of this. I served in the bureaucracy at a senior level, towards the end of my career as an Assistant Secretary of Defense. I think it's picking those two or three priorities and sticking with them no matter what it is.

Because of the time and difficulty of getting things done, you need to focus. I used to tell people that I had the luxury of focus. I only had to work on three things: nuclear, chemical and biological. Know what's important to you and what's not a good use of your time. I think that's really critical.

The other general lesson is follow up on what you say you'll do. It's a basic thing in any walk of life, but if you tell somebody you'll do something, whether it's a foreign counterpart or a colleague, do it.

What’s the US's capability to secure chemical, biological, and nuclear risks today, compared to when you started?

We made huge progress destroying things. Russia had a 40,000-ton arsenal of chemical weapons that we helped destroy, under OPCW supervision. We did a lot of work to secure their nuclear warheads. The tool set that we developed during the Nunn-Lugar programs worked at that time, and we applied them in Syria to destroy the chemical weapons stockpile there in a violent situation. There are Russian facilities that had fissile material, but I worry those relationships were broken off by Putin in 2012. We don't have insights anymore from that on the ground presence and constant interaction.

You can imagine a situation if Prigozhin had been successful, or hadn't turned away from Moscow. It's entirely possible that Russia might have another collapse. The government might split. There could even be a violent conflict, and we still have thousands of nuclear warheads that would be at risk.

North Korea's another hard case, that has a huge amount of materials, weapons and expertise. So while we have that tool set, it won’t be the same thing. It might be less cooperative.

Are there tools you'd like to see added to the toolkit?

I think we need to maintain, exercise and develop capabilities to destroy weapons of mass destruction in the United States. I was involved in a program just a few weeks ago, destroying the last of our Cold War arsenal of chemical weapons. A multi-billion, multi-year effort. But we need to maintain that capability, that technical expertise for destroying chemical weapons because of North Korea, and other potential opportunities in the future.

With Syria, we invested money in developing a transportable neutralization capability called the field deployable hydrolysis system that was built into shipping containers. and we were prepared to waste money. We didn't know if they would ever be used, but we have to have the skills and the technical capabilities available.

Every year, the Pentagon tries to cut the Nunn-Lugar program. Congress rarely tries to cut it, but the Pentagon itself does. You're competing against aircraft carriers and joint strike fighters, and this whole idea of a prevention program isn't classical war-fighting. So we need to support programs like the ongoing Cooperative Threat Reduction Program of the Department of Defense.

You've built a career on preventing things from happening. Is it hard to convince people in Washington that work matters?

Yeah, I think so, because you can't prove a negative. We're always seized by program metrics, and, in prevention work, there's really only one metric that matters at the end of the day. And that's the one time you fail to prevent something.

For an in-depth history of Kazakh decision-making after the fall of the U.S.S.R., see Atomic Steppe: How Kazakhstan Gave Up the Bomb by Toghzan Kassenova. American intelligence cables from the time can be found here.