The Biomedical Advanced Research and Development Authority (BARDA) helped bring Moderna’s mRNA vaccine through clinical trials to market. BARDA’s Division of Research, Innovation, and Ventures (DRIVe) is its in-house biotech venture capital firm, charged with identifying and incubating technologies for U.S. biodefense and preparedness.

Today's interviewee is Dr. Sandeep Patel, the Director of DRIVe from March 2020 to March 2024. Patel helped architect the program’s VC-inspired model and led the organization through its COVID response.

What you’ll learn:

Is BARDA the best value for money in federal pandemic prevention?

Why is it easier to design a new program than fix an old one?

How effective is BARDA’s venture capital-style investing?

Thanks to Rita Sokolova for her judicious transcript edits.

For a printable transcript of this interview, click here:

In a 2022 piece for IFP, Nikki Terran wrote, “Pound for pound, BARDA has easily been the most effective federal agency in our national COVID response.”

Most Statecraft readers, I'm guessing, have never heard of BARDA. Square the circle for me – how is it that BARDA can be so effective and so under the radar?

Yeah, BARDA is an interesting organization. It's very specific in what it does. Its mission is to develop medical countermeasures through public-private partnerships for a variety of public health emergencies. It's highly focused on working with industry on the development, testing, and licensure of medical countermeasures. Because it has such a specific goal, I think it does a great job of just getting that done.

Stepping back for a second here: BARDA’s close to two decades old. It’s housed within the Department of Health and Human Services (HHS). Specifically, it’s within the Administration for Strategic Preparedness and Response, which does a bunch of different things related to emergencies and responses. But BARDA is specifically product development with industry. There's no other place in government that does it in that highly focused way.

Contracting is everything, right? BARDA has other mechanisms for funding, but it typically operates through R&D contracts. More specifically, it uses milestone-based contracts, where there's some deliverable, and financing gets unlocked after that deliverable. How you structure these contracts, and doing so in a streamlined but responsible way, is really important. BARDA is particularly effective at this and has lots of experienced contracting officers who are good at it. So there is a mechanism to work with industry that no other organization within the government has.

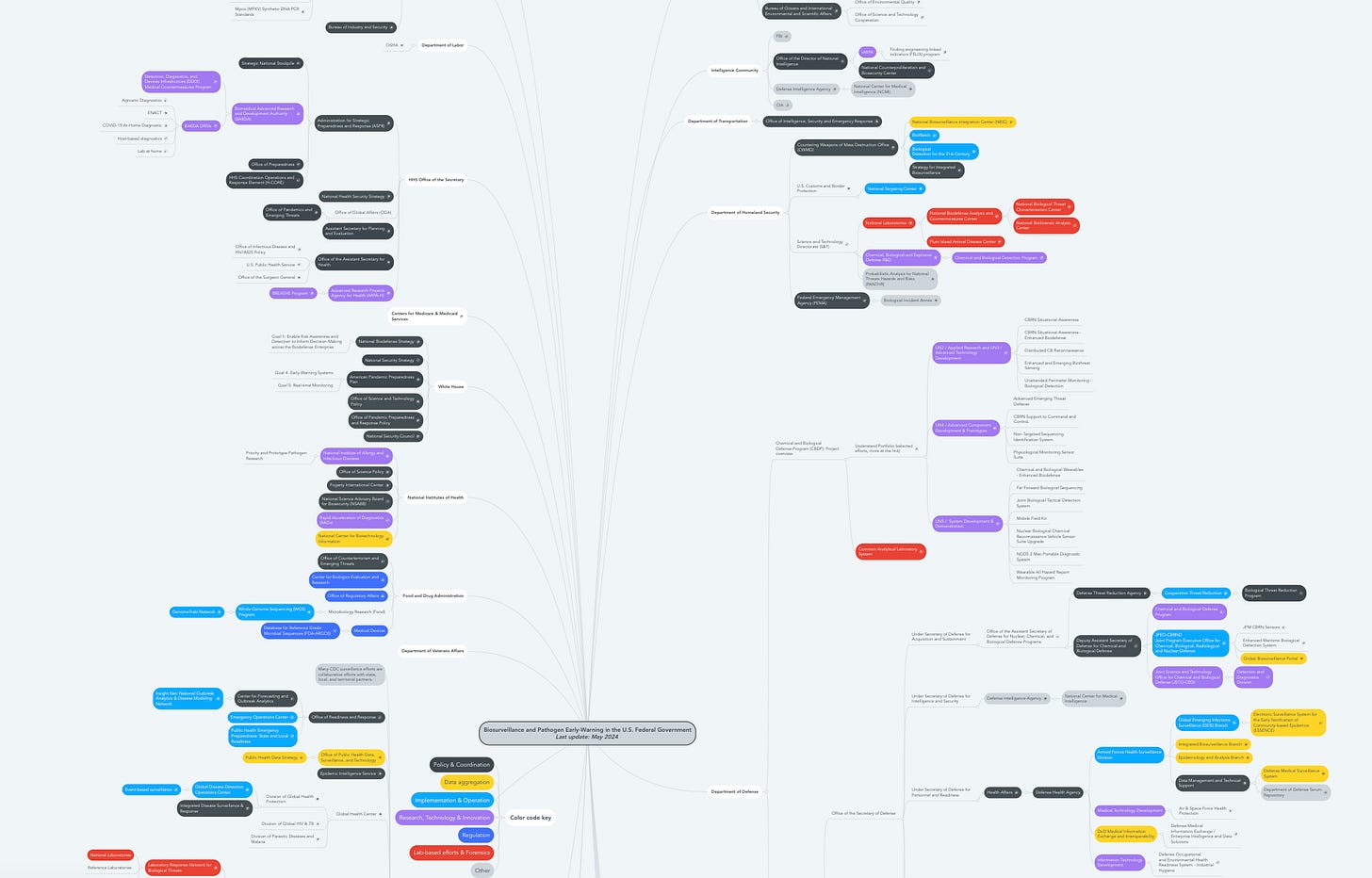

I've got a chart from a colleague of the government's biosecurity and biosafety apparatus, and it seems incredibly sprawling. How does BARDA fit into this broad panoply of biomedical funding? What's the rest of the federal apparatus doing?

There's certainly a web of organizations within the government that fit into this, and BARDA partners with many of them. Some groups, like DARPA and NIH, are earlier funders of the research that feeds into what BARDA eventually does. You also have other organizations that provide information to BARDA and inform its strategy and priorities, like what the CDC might do in terms of surveillance and epidemiological information. The Department of Defense does a lot of product development as well, but the key difference is that the DOD typically focuses on serving the military while BARDA focuses on the U.S. population.

If BARDA hadn't been authorized in ‘06, what problems would you and I face as citizens?

A lot of promising vaccines, therapeutics, and diagnostics would be left in the valley of death. All of the problems that BARDA cares about, like emerging infectious diseases, chemical attacks, and nuclear radiation exposure, are not commercially viable areas. Industry alone is not going to fund the development of medical countermeasures for those things. Absent BARDA, you would see a lot of promising products that aren't licensed and therefore not immediately available for use during emergencies. For example, BARDA funded the vast majority of the COVID vaccine, therapeutic, and diagnostic work as well as for pandemic influenza.

Could you explain the “valley of death” in the biomedical context?

It's an overused term, but two things come to mind. One is the clinical trial stage of development for drugs, vaccines, and devices. This is the most capital-intensive stage of development, and one that the private sector is typically less inclined to invest in unless there's a clear market afterwards. For all the stuff that BARDA operates, there is no clear market at the end there.

The second valley is the one for products and technologies already commercialized but not necessarily tested for use in specific health emergencies. That could be drug repurposing, or applying novel sensing technologies for infectious disease.

Correct me if I'm wrong, but my impression is that while BARDA has a reasonable amount of money to play with, which increased over the pandemic, it’s still small compared to what industry invests in these fields every year.

Yeah, I think it might be slightly misleading because BARDA’s space is so narrow compared to the entire life sciences industry. BARDA does make large bets and will fund phase three trials for drugs or vaccines on par with industry on a per-product basis. When you relate it to industry overall, like life sciences, it's obviously smaller, but I think it's putting the same amount of money for the development as industry standard.

That's a good correction for me. Going back to the milestone-based contracts – as you flagged, BARDA uses them quite successfully. What else should we be using milestone-based contracts for, whether in the biomedical industry or elsewhere?

One of the beauties of milestone-based contracts is that, if they're well-designed, they appropriately spread risk across both partners. Rather than having committed ahead of time to the whole thing, you can put in relatively small amounts of money at the beginning and create gates at each stage to decide whether something warrants further investment. This also benefits the partner on the private side who may not know whether they want to proceed.

A broader problem in biomedical funding, and probably R&D funding overall, is that we don't create enough certainty about next steps when we fund a development stage or project. The number one question that you get from an awardee is, “If we're successful, what's next? Do you have more money?” While milestone-based contracts don't solve that problem entirely, they can provide some certainty. I think there are plenty of other circumstances where creating that unlocking step might actually unlock more private capital. If they see some certainty in downstages, they'll be more willing to invest. BARDA does a lot of cost-sharing in its work where it requires money from partners. I think that becomes a valuable risk-sharing mechanism as well.

My colleagues working on infrastructure policy focus on the problem of uncertainty for developers. If you know something is pricey, but you have certainty about the outcome, it's easier as a private company to choose that path than to choose a cheaper but less certain option.

Is that the same dynamic you're talking about here?

Yeah, I think it's similar. There's another part of the BARDA apparatus that's important, which is the strategic national stockpile. The stockpile, managed by another group within HHS, stores a portfolio of licensed products for use during emergencies. BARDA has a program called Project BioShield which funds the testing of investigational products to licensure and stockpiling. So that's, in effect, a downstream procurement mechanism that BARDA has, which can create some downstream certainty for developers.

My first impression of stockpiling is that there's a warehouse somewhere with a big pile of stuff. Is that the model for Project Bioshield, or is it more complex than that?

It's more complex: there are multiple sites. There's also a vendor-managed inventory, so inventory can exist at a developer's site, and that's considered part of the stockpile as well. And they have a portfolio of products that they support and keep stockpiled. BARDA is one feeding mechanism into the stockpile.

Let's go to BARDA DRIVe, the Division of Research, Innovation, and Ventures. How does that fit into the broader BARDA apparatus?

BARDA and its partners are highly effective, but there's a major strategic gap in how we prepare for pandemics. We identify and prioritize a bunch of threats. So pandemic influenza, smallpox, Ebola — we have a variety of lists. But we can always be surprised. And we need to ensure we’re using the best of our current technological capabilities, in ways we may not be able to imagine. This creates the argument for DRIVe, which can invest in new technologies, new innovators, and take risks that the rest of BARDA cannot.

How do those lists of potential threats get generated?

There are a couple mechanisms. There's an organization called the Public Health Emergency Medical Countermeasures Enterprise (PHEMCE), which is an interagency organization with various components of HHS and DOD and others, that helps prioritize the threats.

The Department of Homeland Security also manages a list of the material threats that they're concerned about. BARDA and other organizations will direct funding based on what's on the list.

Does “material threats” mean literal substances?

Yeah, everything from viral pathogens to chemicals that we might be worried about causing harm.

So these two lists plug into the existing BARDA ecosystem.

Yeah, and this is where DRIVe comes in. When we think about biological threats of the future, like outbreaks of novel pathogens, viruses, fungi, and or other types of threats, there's inevitably going to be a curveball. With SARS-CoV-2, one of the curveballs was asymptomatic transmission. We hadn't been thinking about that or designed a system to respond to that kind of thing, so we had to figure that out during the pandemic.

One of the roles that DRIVE plays, especially in this unknown threat landscape, is to ask, “What could happen in the future? How could it happen in a way that we might not be able to predict or prepare for effectively? What can we do, threat-agnostically, to better prepare and respond to those scenarios?” DRIVe was set up to invest in technologies to frame those problems out.

One example problem is sepsis, which is a dysregulation of the immune system that can follow an infection. No matter what the pathogen is, this is a common mechanism; if we have treatments and diagnostics for it, that prepares us for a variety of threats. Shortly after DRIVe was founded, it created a program called Solving Sepsis that invested in diagnostics and therapeutics, and actually got a couple of products through FDA approval.

Another example of DRIVe’s work is around testing. The paradigm for infectious disease testing is that you have to sequence whatever it is you're looking for, and then you develop a targeted diagnostic, like an antigen or PCR test. The strategic problem with this is that it’s inherently reactive: if a new pathogen emerges, you don't have a way to detect or clinically diagnose it. So one of the things that DRIVe focused on was developing a day zero diagnostic, something that's available before we even know what we're looking for. We developed a whole program around metagenomic sequencing, which is often used for surveillance but hadn't been applied to clinical diagnosis.

The last example I'll mention, which I think is really important, is a bit different. Most of what BARDA does is invest in new technologies and products and get them out. It's really hard to argue for sufficient funds to invest and prepare for things that haven't happened yet. When an emergency arises, then you can solicit investment and Congress will unlock funds, but it’s often a little too late. Ideally, you want to invest beforehand and avoid this panic/neglect cycle of funding.

DRIVe created a program to hedge against this through its public-private venture capital (VC) partnership. The model takes a significant amount of money, say, $500 million — half of which comes from the government, half from private investors — and partners with a group to invest in a portfolio of technologies, as a typical VC would. In this case, the investment is specifically directed at projects within the BARDA mission space. So we’re looking for opportunities that will generate revenue, but then creating an evergreen system where the returns on those investments are reinvested into other technologies.

Go into the potential revenue-generating ideas there. My folk understanding of the value of BARDA and DRIVe is that you're investing in things where there's a market failure or a lack of market interest. How does that all fit together?

Yeah, this gets into platform technologies. For example, an Ebola vaccine has no commercial market other than what the governments would pay for it.

Maybe this is elementary, but why is there no private market for Ebola vaccines?

Ebola, thankfully, is not something that happens in routine healthcare settings. It's very unpredictable and emergency-based. There's no reimbursement system for treating it and it's not financially attractive to work on.

The role that BARDA plays is funding the development of Ebola vaccines. While the product itself doesn't have commercial value, the technology behind it does. mRNA technology is a great example of this that is commercializable, even if the product that BARDA funds isn't. You can imagine new vaccine, treatment, and diagnostic platforms that are all both commercially viable and of interest to national health security. Those are ideal investments for the VC partnership where we're trying to de-risk some of these technologies. They have both a commercial path and a use for BARDA.

I've heard some folks say that people at BARDA DRIVe see themselves as similar to an ARPA in that they're funding disruptive, high-risk tech, and I've heard other folks push back on that and say they're not commensurate. What's your sense of that comparison?

I think it's a different model – it's not an ARPA model, and it's not a typical government R&D model either. We operate by programs, similar to the Heilmeier Catechism method, which is a heuristic that DARPA has used for identifying problems to focus on. It differs in the level of funding, which is a bit lower than you would get in a typical ARPA.

The other key distinction is that ARPAs have tended to focus on deep tech solutions. I would actually argue that that misses a lot of opportunities. There are a lot of problems that I think an ARPA would dismiss because it requires taking a commercial technology and pivoting it or reframing it.

So it doesn't have to be a moonshot technologically, in the way that some ARPA problems have to be.

Yeah. And I would argue that that doesn't make it less challenging. A lot of the problems in healthcare are not around the science and development of products, but around adoption. One great example that DRIVe has focused on is trying to commercialize vaccine patches, which can be self-applied to administer vaccines. This is a fairly straightforward problem technologically, but it has yet to be commercialized. DRIVe filled this unique role for BARDA to advance the development of this technology.

Tell me a little bit more about how DRIVe is structured. What are folks doing all day?

One important thing about BARDA, which is not so dissimilar from ARPA, is that there's a portfolio of active projects organized by programs. At any given time there are something like 14 R&D programs, each with a portfolio of at least five projects.

The teams typically have a program manager, and similarly to ARPAs, there are subject-matter experts, usually contractors but sometimes federal employees borrowed from other groups. Each project team works very closely with their partners. If the scope of a project is to, say, design a device to interpret cough audio signals for signs of infection—which is an active project in the DRIVe portfolio right now—there would be clinical trial experts on the BARDA side that constantly advise the partner on trial design or clinical operations. If manufacturing is part of the scope of a project, we have experts for that too. So a very integrated team forms.

The second thing is that the DRIVe team is constantly scouting and taking deal flow from federal partners. So there are lots of conversations with DARPA and other agencies, private investors, and academia to identify potential partnerships.

I'm guessing some folks in the private VC world would be skeptical that you can get access to interesting projects. Is it harder to get deal flow as a federal agency? Or do you have the benefit of a really broad network of partners across the federal government?

Oh, we have very broad networking. We have DRIVe staff in the Bay Area, Boston, San Diego – all the major hubs. There's constant interaction with investors and lots of eyes and ears on the ground.

We also pioneered a network of startup accelerators across the country, and DRIVe would constantly get flow from these groups about new companies or exciting research, which then flowed to the rest of BARDA. That was a very effective organic network that has actually since been adopted by ARPA-H.

You mentioned BARDA's role in shepherding valuable projects through the FDA clinical trials process. I can imagine my libertarian friends reading this and saying, “Okay, it looks like a big part of the problem is just the FDA process. Maybe BARDA does good work pushing stuff through, but the real bottleneck is clinical trials are way too capital-intensive for companies.” What's your view?

100%. I think the clinical trials process itself is ripe for innovation. And even if you take into account limited budgets and time, the most effective way to test and develop more products is to improve that bottleneck of the clinical trial process. With the COVID response, the part that took the longest was the actual clinical trial. But it's important, right? Because you need to generate sufficient evidence before you proceed. The standards should remain the way they are, but I think there's plenty of opportunity to improve operations so that you could parallelize and more effectively recruit and retain participants in clinical trials. You can leverage adaptive trials that test multiple products.

When I was there, DRIVe created a program to help realize decentralized clinical trials and studies. In the U.S., most of the trial infrastructure exists in academic medical centers, which is not where most people go for routine care. That makes things logistically challenging, especially during an emergency.

So the problem is that you're not getting enough potential members of the trial through the door in these places?

There are a couple of problems with this. One is processing patients, because not enough people run through academic medical centers; for example, rural populations. The other problem is that they're logistically cumbersome and can be complex and bureaucratic to run. Some products are designed for use in your home, urgent care, or retail pharmacy, but we’re not testing the products in those places because we rely on the academic clinical trial infrastructure that's for a hospital center. We're now distributing healthcare in lots of different places but we're not correspondingly improving our trial infrastructure. The opportunity is, “Can we turn decentralized healthcare delivery places into clinical study places as well?”

A lot of the infectious disease home diagnostics that were approved during the pandemic — many of which BARDA funded — were actually never really tested in the home. Up until the FDA approval, they were tested in more controlled clinical environments, yet they were designed for the home. So there were a lot of issues with usability that they didn't figure out ahead of time.

What were some of those usability challenges?

Things like what people do with the test results and how they interpret them. With the antigen test, how do people interpret a half of a red line? That insight would come out in trials that were designed for the home.

What are the arguments against what you're advocating for here?

The pushback is that running trials in more settings makes things complicated for both the participants and the physicians operating the trials. Virtual enrollment, where you enroll on your phone or online, increases the complexity on the ground. The other argument is that it can be more costly.

Where you would land is that there are some products that you would want to test in this system and some products that should remain in the traditional system. We need redundancy in our design so that we have different types of infrastructure depending on what we're doing.

Let's talk more specifically about COVID. What was DRIVe's budget when you came on board?

When I came on board, it was around $25-30 million. That was in year two of its existence, the FY 2020 budget.

And what was the budget when you left?

The baseline budget when I left was about $100 million per year.

Tell me about that scale-up. What was your involvement?

My primary goal was to grow DRIVe’s staff, budget, and impact. When I joined, there were roughly 10 to 15 people on the team. When I left, there were roughly 60. We also expanded the number of programs and the range of work that we did.

In addition to the baseline budget, there was also COVID supplemental money that DRIVe used. DRIVe started with three core programs with that sort of small budget, and based on some of the successes early on, we argued that we needed to do more and put more money in each of the buckets that we had. So we were operating on both at the same time: we were trying to respond to and anticipate how the COVID pandemic might evolve, and at the same time set up some long-term programs.

What did you learn about hiring and talent acquisition through those four years?

Talent acquisition for the government is always challenging, but DRIVe was specifically designed to try to infuse expertise from industry. We were constantly trying to bring in people who had a lot of experience in the private sector, but little in the public sector. We did a lot of recruiting, a lot of referrals, to generate some excitement.

The other challenge with working in the federal government is that, oftentimes, the best people do not want a long-term commitment. You get a lot of people who are mid- to late-career and have enormous amounts of expertise and willingness to contribute to the public sector, but don't want to commit the rest of their lives to working. There’s this assumption that when you work for the government, you're going to be in it for the long haul. We were very intentional about trying to create limited opportunities. ARPAs are known for this model of limited engagement.

Are there ways that federal hiring could better capture the folks who want to contribute in the short term and don't want to sign up for a decade?

Yeah, I think we could. There are lots of fellowship programs that exist to get into government, but they're definitely biased towards early career. It would be really helpful to have mid- to late-career fellowships as well. The fellowships are also relatively short-term and project-based, typically a year or two. I think there is a need to bring in people for four- to five-year terms, similar to a program manager at ARPA but across multiple types of roles.

A more bureaucratic point is that the government is really bad at describing job roles. When you apply for a job with the government, you don't know what job you're applying 90% of the time. When you go to usajobs.gov, you see a lot of generic job classifications. The agency that's hiring might get the chance to write a paragraph that's specific to the role, but that gets buried in this multi-page document. On the back end, multiple agencies and teams are hiring against that generic list of roles. It's a double-sided problem where the agency doesn't know how to target specific people for this, and then the people applying don't know which agency they're applying for.

Let me ask you a prickly question here. As I was prepping for the interview, I couldn't access the BARDA DRIVe website – it returned a 403 error for about a week. Do state capacity challenges like that form a roadblock to folks entering these roles?

Oh, interesting. I wasn't aware of that. That's never happened before.

Is there a drop in IT or systems quality from private industry to the federal government that presents a challenge as people switch over?

Yeah. It's certainly a real issue. It is harder to work with IT and to get equipment that works smoothly, those are all real challenges. The hope is that those issues are minimal enough that people can deal with them and benefit from the good parts of the job. People have come from industry and commented that things don't work as well, but I think they come in with the expectation that they won't work well. Oftentimes the performance exceeds the poor expectation, which ends up being a net positive.

You talked at the beginning of our conversation about how BARDA fills a gap that doesn't exist in the broader federal biomedical apparatus, and that DRIVe fills a gap within BARDA.

Why do these fixes arrive as new programs, instead of as reforms to the broader system?

I think it's strategic and intentional. It's important to separate the brands a bit. So there's a BARDA brand, and there's a DRIVe brand. That’s important because BARDA is known, rightfully, for delivering products and being very reliable as an organization. There's a real trade-off with having that reputation but also being able to innovate and take risks, because inevitably there's going to be failure. This is where it's important to have a group like DRIVe, because it allows you to take those risks and fail. Then you can figure out what's successful, both from a technology and process perspective, and scale that up. There are a number of DRIVe projects that have scaled to BARDA over the years, and I think that model works well. If you try to build things at scale from the very beginning, you're going to run into an issue around the acceptance of risk. You're never going to get out of a conservative mindset, and you'll kill off innovation.

Are we safer now than we were in January 2020?

We're certainly safer for another respiratory viral pandemic, because I think we've learned a lot of lessons on how to handle that. We may not be safer from another unknown threat that surprises us. What I worry about a lot is over-engineering for what we experienced. There's still a lot of work to be done to prepare for all potential future events.

Compared to other federal biomedical funders, BARDA has authorization from Congress to use a much broader suite of procurement models. We’ve talked a little bit about milestone-based payments and advanced market commitments generally. How big of a role have those procurement models and authorities from Congress played in BARDA and DRIVE's success?

DRIVe has experimented a lot with new models of financing. The venture model that I mentioned uses Other Transactions Authority (OTA) — it's actually the only example of this authority being used to set up a venture capital fund. BARDA has both broad authority around the use of OTA and, importantly, a competent, creative contracting staff that knows how to design fit-for-purpose vehicles for the problems it is trying to solve.

[Other Transactions Authority is defined in the negative: it’s a legal instrument that is not a contract, grant, or cooperative agreement. OTA isn’t subject to traditional federal procurement regulations. We interviewed one of its pioneers a few months ago.]

DRIVe has also pioneered the use of prizes and is incubating other pull incentive models. DRIVe already organized a prize over the last few years and is using OTA for a much bigger prize later in 2024.

We talked to Rick Dunn, who pioneered OTA use at DARPA, which he brought from NASA. To put it lightly, he doesn’t trust the ability of federal contracting staff to pick up OTA. It sounds like you have a different view. What makes BARDA's contracting staff creative and competent users of OTA?

One of the problems with OTA that I've observed is an unintended negative consequence of creating so much freedom in contracting. What can happen is that, because there aren't processes and rules built around this, there might be risk aversion. Suddenly there are clauses that you don't have to put into a contract. What do you do with that? You need the right kind of person who can operate under those uncertainties, at the edge. Someone who can put together and negotiate a contract in a creative way, but does so responsibly.

One of the things BARDA has done within DRIVe is set up a separate OTA team. Its job is to perfect the craft of using the OTA in different scenarios. The venture example is pretty unique, and setting up the venture capital partnership required a lot of creativity. How do you craft a contract to deal with returns on investments? This is non-standard, and requires a whole new way of thinking. We had a really great team that thought through how to deal with that financially.

Could you walk me through the story of the venture model? How did it come to be?

So this is a longer process that predates me. BARDA had preexisting Other Transactions Authority, but it was unclear whether that authority could be used to fund a venture capital partnership in that way.

When you say that it was unclear under the existing OTA, was it just that nobody had done it before?

Nobody had done it before, so nothing like this existed. There were some analogs, and the government had invested in groups that do venture capital partnerships, but there were two unique aspects to how BARDA was envisioning this. One was that we wanted to mix public and private capital into one pool, so it wasn't just the government funding companies through a typical venture capital model. There were questions about how that could work, and the conflicts associated with it.

The other piece was figuring out what would happen to any returns generated from these investments. The whole idea of a venture capital partnership is that they make an investment, they generate some return, and then they take that money as profit. What we were trying to do was unique because we wanted to create that evergreen system, self-sustaining system. The life cycles there were really important. If we have a 10-year contract with our partner but want this to exist in perpetuity, how do we deal with things that are beyond the contract?

So you got the formal authorization in 2017. What did getting venture partner buy-in look like?

Yeah, we got the authority in 2017, and in 2018 a team was set up to do market research, basically talk to every public and private investor, figure out all the models that existed, what didn't work, what worked. It was a massive amount of scouting that took a couple of years to do, because this was not expertise that anyone in HHS had. There may have been a few people in some other organizations within the government that had it, but it was few and far between.

That led to a competitive solicitation for a partner who could be the venture capital investor. The way a typical venture capital structure works is that a general partner (GP) manages investments in portfolio companies and operates a fund. The money that they use to operate comes from limited partners (LPs). In this scenario, BARDA is like the anchor LP. As part of the solicitation, we required that the GP attract other limited partners into the space.

We put out the solicitation during the pandemic, in November 2020. It was actually really hard to get lawyers and budget officials and others to think about this really complex procurement in the midst of a pandemic.

What did you do to protect that space?

We framed this as a pandemic response tool. We always thought about it that way before, but we emphasized that this would be a key part of the long-term pandemic response. If we set it up quickly and effectively, it could immediately start investing in things that would be useful in the long tail of the pandemic. That's how we created some urgency within the organization.

What were the return profiles offered to other LPs, given that BARDA was reinvesting?

That was the unique part. BARDA had already contributed $250 million. That's money that would go into the investment cycles in perpetuity, so the government would never get it back. Any positive returns just get reinvested over and over, and hopefully those grow over time. Other limited partners had their own agreements, and it was up to them and the GP to negotiate that.

That's obviously an inventive model and you had to really fight to do it that way. What lessons would you draw from this for policy entrepreneurs elsewhere in the federal government?

It's helpful to have a policy window where there's clear acceptance that the issue that you're trying to solve is important.

And I can't say enough about having a core team that is full of incredible high-level talent — this includes contracting officers, finance, budget, and lawyers. If you don't have a group that's willing to create something new, you won't get something new and inventive.

Anything else I should have asked?

Yeah, I think one thing that's worth noting is that there are three segments within the funding: philanthropic, government, and private industry. Those sectors have different motivations for investments, but they're all interdependent. A lot of the problems that we see in terms of the pace of innovation and R&D are due to a lack of transparency or sharing of expertise across those three segments of funders.

Something that we focused on is, “How do we take a little bit of capital and leverage massive amounts of capital from other groups?” This venture capital partnership is designed to do that more directly, but a lot of things BARDA does are designed to try to attract other forms of investment. It’s a really important area of opportunity. Everyone tends to think about this as a competitive thing but, in reality, I think they all act as a flywheel and actually reinforce one another.