This week’s interview is a little different: it’s a live recording of a panel I hosted three weeks ago at the Bottlenecks Conference in San Francisco.

Broadly speaking, Sam Hammond is interested in state capacity from the right, and Jen Pahlka is interested in state capacity from the left. I was particularly interested in getting answers to a question about the political economy of state capacity. Specifically, is there actually room for a political coalition for state capacity? Maybe we agree in theory that the federal government should work better. But in practice, what if we mean entirely different things?

Hammond and Pahlka graciously indulged that question and others, including:

Should Trump implement Schedule F?

Why is it so hard to get rid of fax machines in government?

What cues should today’s reformers take from the Progressive Era?

What is Canada doing right?

Brief bios: Hammond is a Senior Economist at the Foundation for American Innovation, where he focuses on AI policy. Pahlka is a Senior Fellow at the Niskanen Center and the Federation of American Scientists, and the author of Recoding America. We’ve interviewed her before.

Thanks to Rita Sokolova for judicious transcript edits.

For a printable transcript of this interview, click here:

Do you two disagree about state capacity? You’ve both written about policy implementation, but Jen spends more time on it. Sam, you talk about regime change as a natural consequence of technological innovation. Jen, I don't hear that phrase from you. Do you two conceptualize this whole conversation differently?

Samuel Hammond: If you look at people like Matt Yglesias or Ezra Klein, you can interpret their role as translating things that are already taken for granted by the right for progressive Democrats. They did that for housing and a few other issues, and now they're doing it for state capacity. So I think there's a freebased version of state capacity. They’re helping folks who are part of a coalition that is the main inhibitor to state capacity to assimilate those ideas.

Jen Pahlka: If the question is where Sam and I disagree, I think that there's likely far more agreement than disagreement. I'll start with the fact that if you come from the left, you're constantly told that the right doesn't care about state capacity at all, which is not true. I think the left is, probably correctly, concerned with state capacity in ways that you are not, per your post on the Effective Altruism (EA) case for Trump.

But we're both talking about a world in which we stop having massive denial about tradeoffs and say, “No, these things aren't good, but these better things are more valuable, so we're going to take the loss to get a win.”

What are the obvious, no-brainer improvements to state capacity we can make?

SH: We both see where the problems are, but my view is that they're a lot worse and less fixable through incremental reform. Any major structural reform will have to be bipartisan, and that's going to require having factions in both parties build a new consensus that the system is fundamentally broken. And you need some kind of exogenous ability to critique that incumbent system, because if you come from within, you're just going to get co-opted. A good example of this was the Endless Frontier Act, which became the “Science” part of the CHIPS and Science Act [See the Statecraft interviews on the passage and implementation of CHIPS]. The Endless Frontier Act was initially put forward by Sen. Todd Young (R-IN) as an idea to build a separate but parallel tech directive for doing applied research and for programming $100 billion at the NSF. As that proposal worked its way through the horse-trading in Congress, you saw every former NSF president or university president come out of the woodwork and write articles in The Hill saying that this would destroy the NSF’s mission.

At the end of the process, you got something that was very watered down. It marginally increased support for science, but it didn't get to the fundamental issue. We have a grants-based model of science; if we were doing the Manhattan Project today, there would be like a thousand requests for proposals (RFPs). We need to transcend that system, and that’ll require people waking up to this on both sides of the aisle. Instead of the axis being left or right, it has to be “broken or not broken.”

JP: I very much agree — we have to just stop that. It’s like the Judgment of Solomon: if you say, “You shouldn't have the baby, I shouldn't have the baby, we'll kill the baby,” then nobody has the baby. And that's kind of what we're doing now. If you don’t want the other side to have the capacity to do things because you don't agree with their agenda, and you don't have it either, then nobody has it. I think that Sam is looking more at how things are getting watered down at the legislative level. I'm looking at what I call the cascade of rigidity that happens after that watering down, where even the gains get eroded because the bureaucracy is risk-averse.

Will you give us an example of that cascade or the implementation challenge from your work?

JP: The story that I've probably told the most is about a friend of mine who worked on a project at the Air Force. Back in 2014, we were trying to get new software on the satellites that manage GPS, and the project was extremely delayed and way over budget. They had inserted a huge enterprise service bus (ESB) in the middle of a really simple protocol; it was so complex and Rube Goldberg-y that it caused timeouts between the ground stations and the satellite.

He asked why this ESB was in there, and someone said that it's a requirement in the contract. As he pulled the thread, he found out that everybody believed this was required by Congress. So he went back and looked at the Clinger Cohen Act, which requires all agencies to have a plan for how they're going to handle technology. At some point, somebody wrote some guidance around that, which suggested interoperability using ESBs — for software developers who are asking, “Why is she talking about ESBs?”, this was in the ‘90s. As it descended from the federal enterprise architecture to the Department of Defense enterprise architecture to the US Air Force enterprise architecture to an actual contract, it went from being a suggestion to a requirement.

So you have something that comes from Congress or the White House that's pretty on target and very generic and flexible, but as it falls through that cascade, it becomes incrementally more rigid, more specific, and less able to withstand the test of time. This actually jammed up the software to the point where they couldn’t get it out and had to ship the satellites with the old software. Even when we get things right at the legislative level, we screw it up at the implementation level.

Sam, is it fair to say that you think that AI will make a lot of these questions obsolete? Are we barking up the wrong tree with small implementation tweaks?

SH: Yes and no. There are often small tweaks that can have ripple effects across an organization. But my view is that there are two deeper sets of issues. One is the broader issue of lack of trust from Nixon onward. You may make a persuasive argument that we need to empower the executive branch to make more unilateral decisions, but if you're a Democrat and you're worried about Trump getting in, you also want to constrain the executive, and vice versa. It leads to an accumulation of constraints on authority.

The second thing is a deeper political economy issue. We’re living on burning down the capital of the New Deal era. Our Social Security numbers are from 1936 — and they're all hacked now, by the way. The IRS is built on mainframes from 1965, which still use the same Assembly code from John F. Kennedy's administration.

JP: We're working on that.

SH: There’s a funny story about how the guy who was migrating the IRS master file from Assembly to Java had his contract expire. Now he's working at the Social Security Administration.

The Long Twentieth Century, which I think of as the middle period of the Great Society era, saw the decline of parties and unions, and more power shifted into large foundations, which pioneered the grant-based model. People in San Francisco know how much money gets filtered through nonprofit organizations. I think of that as a privatization by another name, and it’s one of the sources of today’s diffuse authority.

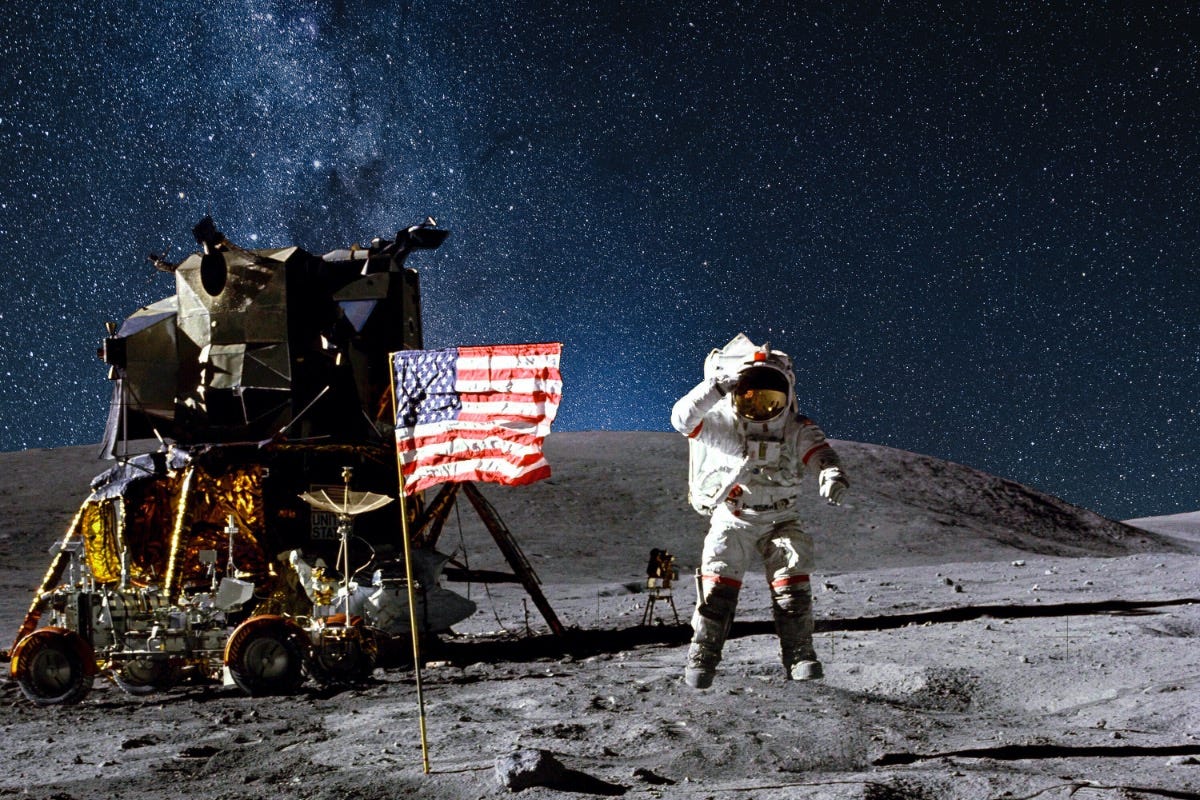

Thinking in terms of long periods of history, that is due to change. We’ve had multiple change-focused elections where nothing actually happened. Changes are ultimately driven by shifts in the technological base. The worlds of 1900 and 1950 were totally different, and that’s how we got the New Deal — 1900 was before the Wright Brothers, and by 1950 we had every three letter agency and were going to the moon. In the early Progressive era, some of the first industrialists were building the first large corporations, and they had a new science of management about how to actually have direct reports and supervisors and so forth. That was eventually brought into government and led to the administrative state.

If you think of AI as a technology that fundamentally implicates how we structure an organization, we're going to go through another transition in the same way that Uber and Lyft displaced regulated taxi commissions. We’ll either reform the government to embrace those new models, or things will get so bad that basic government functions will get displaced into the private sector in the same way that we now rely on SpaceX for what NASA did in the past.

Do either of you take last century’s progressive reformers as a model for the state capacity work that you do now?

JP: I think it's a reasonable model to look at, in part because it was bipartisan.

SH: Yeah, a lot of people on the new right take inspiration from early progressive voices like Roosevelt. Those waves of progressivism were partly a critique of patronage, clientelism, and corruption; now it’s a critique of nonprofits winning a contract and just putting that money toward executive pay and not actually doing anything — you know, going to Argentina to study their bus stops, that kind of thing.

The corruption we have today is more opaque. It used to be Tammany Hall-style stuff, and now it's filtered through opaque organizations and dark money groups. These are structures that we've inherited, and they were designed in part to be resistant to reform — probably to have that cascade-of-rigidity effect by design.

The liberal legal network of the ‘50s and ‘60s eventually turned into a kind of special interest liberalism, where the idea was to use public choice problems to our advantage. We built programs on top of a constituency because that constituency will lobby for that program and make it hard to repeal.

A good example of this is the Special Supplemental Nutrition Program for Women, Infants, and Children (WIC), which provides vouchers to purchase baby formula. Half of the mothers in America get baby formula through the WIC program. During the pandemic, there was a massive baby formula shortage. Why? Because the WIC program was set up so that every state grants an exclusive manufacturing contract to produce the formula. If you win that contract, you have 100% of the market. That was by design: if you're worried about Reagan repealing the WIC program, make sure every single state has a constituency that will lobby against it.

That model works fine if you're at the end of history where nothing is changing, because you can lock things in. But if you lock things in and expect history to continue and technology to change, that delays necessary reforms to the point of crisis.

JP: Another way to think about the comparison to the Progressive era is returning to the “how,” not just the “what.” Ironically, some of what we have to undo now was built then. Civil service reform is desperately needed, and they were talking about it then too, but we're actually going to undo what they did. In that era, people really needed new models of professionalization, and then we just let that rot. We too seldom bring our attention back to the “how,” and it needs a huge refresh. So we're both inspired by the Progressive era and will also need to dismantle a bunch of Progressive era wins.

So it sounds like you want to purge a bunch of patronage from the existing system, but also to implement Schedule F, implying free placement of “my guys” throughout the system. Sam, can you square that circle for me?

SH: I'm Canadian, and my favorite Prime Minister was Jean Chrétien. In 1999, he unilaterally passed a budget that fired a third of the civil service. To me, this is not as insane or radical; in Canada we have a democracy where, if you have the majority, you just run the government. This is common across most parliamentary systems: they shut down ministries and start new ones.

America seems uniquely sclerotic in this sense, partly because of the Congressional structure and checks and balances. But we have had periods where we did build new things — Vannevar Bush started what became the Manhattan Project with a two-page memo to FDR, which was approved in 14 days. We could do that again, but it's going to require purging a lot of the plaque that's built up in the system.

This isn't about going back to a spoils system where we're appointing the My Pillow guy to whatever. Hopefully it brings some fresh blood into the system. The new industrialists and JP Morgans are like Patrick Collison; the Secretary of Defense should be like the Palmer Luckeys of the world. These are people who understand the scale and extent of the crisis that we're facing. In the case of Elon Musk, for example, they have a very different sense of how to manage an organization. Musk calls it a subtraction approach — if you're not subtracting things from your product until it breaks, you're not subtracting enough. You can always add things back in.

Jen, what's your vision of civil service reform?

JP: Sam and I agree that you can't really run a government when you can't fire people. People will tell you, “Of course you can fire people,” but on a practical basis, it takes so much time that it's a choice between doing anything else and “managing out” an employee. Schedule F doesn't fix that, which is a big problem. We need to reform the civil service, not slap some veneer of reform on top of it that doesn't work and can really only be used in certain situations. Schedule F doesn't actually put any system in place for real accountability.

I think the left needs to really look in the mirror — I’m stealing Don Kettl's line, but you can't fight something with nothing. The left has not put forth a credible vision of what civil service reform would look like that gets to the outcomes we all want. So Schedule F looks appealing, but it just doesn't do anything that we need civil service reform to do, and it really gets at the independence of civil servants to be able to stand up and say, “You know, this is what the science says.”

In the interest of building the cross-party consensus that you guys have both mentioned, I would like each of you to name something good that the other side of the aisle is doing for state capacity.

SH: You could make the case that California YIMBY has been the most successful advocacy campaign of the last decade, and that's coming predominantly from moderate Democratic voices. So there is a faction that understands these issues really well, but they're a minority. CA YIMBY can have very outsized power, partly because even though they're outnumbered by the NIMBYs, the NIMBYs are suffering under their own problems of diffuse authority and they're not actually coordinated.

JP: In general, I feel like the right has got great thinking. There's so much in terms of permitting reform that you can give Republicans a high five for.

If you want to improve state capacity, you have to do three things: you need to have the right people, focus them on the right things, and burden them less. We may disagree a little bit in terms of Schedule F and how to get the right people, but the right obviously has a huge legacy of getting government to focus instead of trying to do everything. So I don't think Sam's totally wrong when he says Ezra Klein is just making ideas from the right more palatable for progressives.

Burdening public servants less is an area where the left and the right need to come together, but neither of them really gets it. There's been a thesis on the right that burdening public servants decreases the burden on the public, and it's just wrong. It's absolutely disproven, we're just not looking at the evidence.

Today there’s increasingly a consensus across the parties that we need to be able to build more housing. There’s beginning to be a similar consensus on building more generally: the idea that our permitting regime is stopping us from building infrastructure and energy we need.

Are there other, similar areas where you're hopeful that a similar bipartisan consensus can develop?

SH: Broader industrial policy issues. Everything-bagel liberalism, right? When a party enacts a program and begins to own it, that gives them some motivation to make sure that it works. Within the Biden administration, there has been a faction of folks who understand these issues really deeply and are working on piecemeal things to make sure that money actually gets out the door and goes to productive projects. You know, there's always a little bit of a graft in these things that you sort of have to take.

Canada also has a housing issue, but Toronto now has more fixed construction cranes than every US city combined. Why? Because the province established the Ontario Land Tribunal. It's an administrative body that has the ability to override judicial review and local decisions on land use. You have NIMBYs in Toronto saying, “Don't build here,” and they're just like, “No, we're going to build here.” That would strike most Americans as deeply unconstitutional. There's this idea of state capacity libertarianism — I call myself a Robert Moses libertarian. I don't know if that’s an oxymoron. There's a gray area in the law that gets exploited in moments of crisis.

My biggest complaint about COVID was just how little we did to actually fix deeper issues. We are in this complacent mode — we've fallen into what you could call a fiscalist regime, and all we can do is pass massive reconciliation bills that spend more money on broken existing programs. I’m blackpilled by the fact that lines around the block to claim unemployment insurance and websites having business hours where you can’t use them after 5PM were not enough motivation to actually drive reform. I think we could probably fix those systems. Private sector organizations build parallel systems that just replace the broken thing, and the public sector probably needs to do that. When things get so broken, you're often better off starting greenfield.

JP: I actually don't disagree with that. We just also have to understand that if you don't manage that really well, it's a very bloody process. In some sense, it's actually not about issues, but about whether you think the government should do X or Y. If the government can do neither of those things, it's deeply unsettling. Sam mentioned trust and faith in government, and I do think we have to just go for it: if we say X, we're going to get X done. We should fight those fights on the political level, and not through friction.

On the other hand, it is all about the issues and the outcomes. I thought Noah Smith was really good on this when talking about whether neoliberalism was good or bad. He said that the abundance agenda is to stop thinking so much about the ways neoliberalism has constrained our thinking to process ways, that it’s really about just saying, “We want these things, let's go get them and shape the process to get the outcome,” not the other way around. I would imagine that we probably agree on all the things that are on that abundance list. We're trying to create a government that just gets those things for people.

Jen, do you share Sam's blackpilling over the COVID response and the amount that's been done since?

JP: I do. He brought up the state unemployment insurance delivery — almost none of that has been fixed. New Jersey's done a great job, and a couple of other states have gotten a little bit better, but it’s essentially just doing the same thing we did pre-COVID. We didn't fundamentally change the model by which we develop that software or deliver that service. We didn't do any policy or process simplification. We just said, “Oh, let's throw more money at Deloitte and hope that they can fix the thing that they broke in the first place. Every time we give them more money, it gets worse, but let's just keep doing that.” That's a perfect case in which we've made very, very little progress because we haven't changed the model.

There's this received wisdom that exogenous shocks create opportunities for disruption, reform, and innovation, in both the private and public sectors: World War II, for example.

But you’re saying that the exogenous shock of COVID didn't have these disruptive benefits. So should we be doomers about everything?

JP: I don't think we had a field ready to deal with that and to channel that energy toward something sustainable. We need to now build that field so that with each successive shock that we have to go through, we use that energy to pull towards a new model that we can articulate. It's like what Don Kettl said, you can't fight something with nothing. As reformers, we had nothing. So we should be working on that all together right now.

SH: Yeah, I don't want to try to defend the right as a monolith because I don't think it's a monolith. In fact, I'm speaking for reform on the right. Balaji Srinivasan was shortlisted for FDA commissioner. I don't think of him as necessarily on the right, he's sort of on his own axis. But had he been the FDA commissioner, the pandemic would have been over in like a month. There are opportunities, but it's driven by leadership. You need someone with vision that you invest a lot of trust and authority in.

We tend to respond to crises with more diffuse authority — we're worried about the vulnerabilities in our cybersecurity infrastructure, so a congressman proposes funding scholarships to DeVry University for cybersecurity. That’s how we do things now. But if there's a World War III, America does have the latent capacity to build a lot of ships and giant fleets of drones. Part of the issue with COVID was that it was in this middle ground of being a bad disease, but not that bad. It allowed for these luxury beliefs to continue. You don't want to wish that it was worse, but it was not bad enough and let us continue doing these kluges.

JP: Yeah, I agree with that. We really have to give the thing that we want to move toward a name and let people target it, because I feel like the whole government reform space is just like, “That's bad,” instead of, “That's what good looks like, let's go over there.”

What is the low-hanging fruit on state capacity? And then pie-in-the-sky ideas?

JP: I'm really interested in the Paperwork Reduction Act, which I only ever refer to as the “Comically Misnamed Paperwork Reduction Act,” because it only creates more paperwork. I do worry that folks on the right still have that broken idea that creating the burden on civil servants reduces the burden on the public. When I talk to Republicans about this and ask, “Does this thing actually do what you want it to?”, they're much more open to it than I would have expected.

SH: Targeting the Paperwork Reduction Act is great and necessary work, but the system is a multi-headed Hydra: you cut off one head and three more grow back. Part of Biden's executive order on AI was to create a new Office of Management and Budget (OMB) directive where every use of AI in government now has to pass through four different consultations, including retrospectively on things that we are already using, like translation services. Apparently the U.S. Postal Service has to make sure that their system for routing letters isn't rights-impacting. That does not bode well for getting AI bureaucrats. My model for a good OMB rule is that your Chief AI Officer is asked, “What did you automate today?”

JP: I totally agree with that, and I wrote about what happens when AI meets the cascade of rigidity. We're 100% on the same page. One of the reasons we don't have an AI talent surge — we’ve hired some people but it really is not commensurate with what was intended — is because we don't have anybody who owns things in government. Before we can hire AI people, we need to hire product managers who have some degree of ownership over the thing that they are running, instead of this incredibly diffuse way of managing things where everybody gets to do a little bit of this, a little bit of that.

If you don't have an owner, you don't know what your uses for AI are. Right now, they’re going to agencies and saying, “You guys are supposed to hire 50 AI people.” And they're like, “We have zero idea what we should use AI for because we don't know how our own systems work.” There are some first-order problems that we need to deal with. They’re not about innovation, but basic issues like how to structure government for accountability.

SH: If AI drives a massive increase in drug discovery where we go from 50 new drugs a year to 500,000, getting copilots to FDA officials is not going to cut it. We would need a totally different process, and potentially one that employs very few people. You could imagine totally new ways of governing with AI where civil service reform looks more like there's no longer a civil service, there are just AIs doing the work. We used to say “getting to Denmark,” but now I say “getting to Estonia.” Estonia has one of the most sophisticated e-governments in the world — it’s all cryptographically secured on a distributed blockchain. There's an open API, so everyone can develop services that interface with government services. We're a far cry from that world, but that's the world we need to get to if we want to deal with cybersecurity issues, drive output legitimacy, and build scalable solutions.

Almost by definition, you can't scale a labor-intensive process. We need the Community Notes version of everything — trusted systems to the extent that the algorithm is open and anyone can audit it, but it is quasi-decentralized because it's harnessing the wisdom of crowds or AI in some new way or through some new process that's not going to come from within.

JP: Do you think about using AI for regulatory simplification?

SH: One hundred percent, yeah. You know, regulatory budgeting was another idea stolen from Canada. That was the liberal party idea in British Columbia.

No more ideas from Canada, please. I’m cutting you off.

SH: In 2014 the Mercatus Center ran the RegData project, which used very simple natural language processing to flag every part of the Code of Federal Regulations (CFR) that said “shall,” or any other word that suggested stringency. That was a very dumb approach. But we now have large language models that could read through and easily quantify which parts of the CFR are actually creating onerous or redundant restrictions. Instead of a one-in, two-out rule, we should probably have a one-in, twenty-out rule.

JP: When I read your “EA case for Trump” piece, I thought of an interview I did with a woman who worked at Center for Medicare & Medicaid Services (CMS) under Trump. They were trying to get rid of all the regulations that required faxing. This was a four-year thing under Trump, and Seema Verma was 100% behind this. She had a team on it. They would find the requirement and actually undo it, but then two years later, it would repopulate because they didn't get the thing that it was referring to. It just comes back like a cancer. We didn't get it all, which is hilarious because I think Seema was interested in doing this because her husband had cancer. This is a perfect cancer metaphor.

Operation Warp Speed was pretty cool. There are other things that the Trump administration tried to do but that they couldn't get done. To me, one of the most exciting uses of AI is that it can track down all of those references and how all of the requirements are intertwined and actually get rid of something like fax machine regulations. We ought to be using it for that kind of thing.

What is something that makes you hopeful? Give us a white pill for the state capacity movement.

SH: The Elon Musk government efficiency commission.

JP: Direct File from the IRS. Fantastic product. I think something like 90 percent of people that used it gave it five stars.