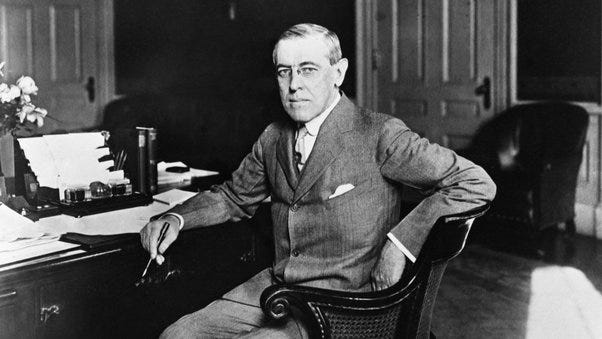

In 1919, President Woodrow Wilson suffered a major stroke. The president, a widower, was kept in solitude by his second wife and a tight ring of advisers. For months, senior executive branch and legislative officials could not see the president. The White House claimed the president would shortly return to full health, and that he suffered only from “nervous exhaustion.” His wife managed the flow of information to him, sharing certain memos and concealing others.

The president was desperate to cement his legacy and did not consider resigning. In fact, he felt confident he could run for another term despite his acute medical condition.

In an open convention, the Democratic Party took 44 ballots to choose his successor. In the subsequent general election, Warren Harding won with the largest popular vote margin ever for a Republican candidate.

Noting the parallels between recent events and Wilson’s story, we spoke to John Milton Cooper Jr., a historian who has been called "the world's greatest authority on Woodrow Wilson." Cooper is Professor Emeritus at the University of Wisconsin-Madison. His Woodrow Wilson: A Biography was a Pulitzer Prize finalist.

We discussed:

How did the White House hide the president’s condition from Congress and the public?

How did the Democratic Party handle his commitment to run for president again?

Was the president fully aware of his own condition?

How were affairs of state managed while the president was incapacitated?

Before 1919, as I understand it, Wilson had already had three previous strokes. How did they affect him?

Yes, starting in the 1890s, but there's a bit of controversy about it. What we're dealing with is mainly anecdotal evidence. You don't get any kind of medical examination of Wilson until 1906. The earlier ones, he probably had what we would now call TIAs, transient ischemic attacks, relatively little things.

The earliest incident that we have real medical evidence about was in 1906, while he was president of Princeton. He woke up one morning and found he had lost most of the vision in one eye, which was very disturbing. He went to Philadelphia and was examined by both an ophthalmologist and a neurologist, Dr. Francis Durcum. They found hardening of the arteries, evidence that Wilson had a circulatory condition with neurological consequences.

The advice they gave him was: quit work, no stress, and so forth. Given the kind of, shall we say, driving person that Wilson was, he didn't like that. He took the advice, to the extent that he took off and did a long holiday biking summer adventure in Scotland by himself. He was examined then by a leading neurologist in Edinburgh, and that doctor said to him, “No, you can keep on working, just pace yourself, be sensible.” He was hearing what he wanted to hear, so that's the advice he followed.

Now, some argue — and I've argued this myself — that after that, Wilson became more driven. In other words, this was a marker, a warning sign.

That's the one that we have real evidence for. Now, there are some other times that he reported numbness and things like this. It's hard to say what they really were. The prevailing view among historians and biographers is that Dr. Weinstein, who wrote a very good medical and psychological biography of Wilson, overdiagnosed him. The book reads as if every time Wilson had a cough, that’s immediately a sign of neurological decline. It's hard to say.

When I wrote a book about the fight over the League of Nations, I was teaching at the University of Wisconsin, and I consulted with a friend of mine, the chair of the med school neurology department. I had him read some of the relevant documents, and he said that, in terms of ability to perform, people who suffer strokes like Wilson's can be going on almost all cylinders. They can be at 90% or so right up to the time that it happens.

Wilson also had a bad bout of something, which I think was pretty clearly flu, when he was at the Paris Peace Conference in 1919. Evidently his behavior changed, and he became a bit more testy and suspicious. Again, these are anecdotes that come out and then, aha, after the fact, they seem to indicate things.

When Wilson suffered the stroke, he had been out on a whirlwind barnstorming tour across America to try to sell the League of Nations. He basically broke down. He just couldn't continue. So they curtailed the trip and brought him back to Washington where he was secluded in the White House.

Now, the wisdom at the time was to deal with strokes with seclusion, quiet, rest. Carry Grayson, the White House physician, later claimed that he was suspecting a stroke. That's hard to say.

Grayson kept one diary at the Peace Conference, which is one of the major sources for what Wilson was doing and thinking. We have the original diary in a manuscript. The diary for later, there's only a typescript, and I've suspected — and I'm sorry for the pun — that Grayson may have doctored it a bit, in order to claim that he saw the stroke coming.

To be clear, Grayson said he believed on the speaking tour that Wilson had suffered a stroke?

No, that he showed the signs that he might be suffering a stroke in advance of his return to the White House. One thing that I think you can say definitively about Wilson's physical condition is that he was not at his best.

He had really worn himself out at the peace conference. It'd be these 12, 14-hour days of negotiation and hard bargaining, It was really difficult.

I recently read Robert Kagan's The Ghost at the Feast, a very good book. I wrote a fan email to Kagan and said, “I wonder if the fight over the League of Nations might have turned out differently if Wilson had been at the top of his game.” Because if you look at Wilson in that first term, it was remarkable. I mean, this man is one of the great politicians, one of the great leaders of American history. Yale presidential scholar Steve Skowronek once called this “a virtuoso performance,” which it was. Now, if Wilson had been on the top of his game that way, you can't say things would have turned out completely differently. But certainly, the events would have gone differently.

Well, anyway, they secluded him, and he was apparently functional. He watched movies, he played pool, and, you know, kind of kept quiet. And then, about five days after they returned to Washington, that's when he suffered the stroke.

There are several accounts of it. What I believe happened was that he suffered it in the night, didn't know it, woke up, tried to walk across the bedroom to the bathroom, and slumped down. Others believe he was in the bathroom, had a sudden stroke, and fell and cut his head.

I'll give Grayson credit for this foresight: he had already called for Dr. Durcum to come and examine Wilson. That appointment was already in the works. When the stroke happened, Grayson got on the phone to Durcum immediately and asked him to come right away. So Durcum did. Grayson met him at the train station, briefed him in the car going there and Durcum examined Wilson.

We have one of the country's leading neurologists examining the president within hours of his stroke. Durcum said the kind of stroke that Wilson suffered was an ingravescent stroke. That means the kind of stroke that's caused by clots, as opposed to a hemorrhagic stroke, or what is called apoplexy. We have a better idea of what ailed Wilson than for just about any other president before, because of these detailed, contemporaneous medical records.

Now, there's a story that Mrs. Wilson asked Durcum, “Well, what should we do? Should the president resign, and Vice President Marshall become president?” And she says that Durcum said, “Oh, no, no, Mrs. Wilson. No, no, no. He should work. Staying on his work is the best thing for him.”

Well, in his book, Weinstein absolutely correctly says that is something that no responsible medical professional would say. Edith Wilson's motivations and behavior, we can get into that in a bit.

I'd like to, yeah.

What made the effects of the stroke so bad was not only the stroke itself. That's the underlying condition. But, a few days after that, from what little we know, Wilson was not that incapacitated. He had this paralysis, but he was fully conscious, he was being informed of what was going on. In fact, the Cabinet was meeting without him, and he didn't like it and made his dislike known to them and shut that down. But a few days after the stroke, he suffered a urinary tract infection that became life-threatening — he had a high fever, in and out of consciousness. The big question was, surgery or not? Do we operate or don't we? Obviously, surgery on a person of his age and physical condition was dangerous.

They called in a Dr. Young from Johns Hopkins, a specialist who advised against the surgery, and he said, “Let's try something else,” which was to use hot compresses to try to loosen up the obstruction. It worked, but that whole episode debilitated him more.

When my neurologist friend read these different documents, he was particularly interested in the psychological effects of the stroke. He thought an awful lot of Wilson's strange behavior when he was back to some degree of activity was the consequence of solitude. He said, “That's exactly what they don't do now for stroke victims.” The medical wisdom at the time called for solitude, nothing to upset them. “Now,” he said, “What they try to do is get stroke victims into social interaction as soon as they can and get them back into as close to normal life as they can.” He really thought the psychological effects on Wilson were probably as much due to solitude as to the stroke itself.

And what were those psychological effects? What was the change in President Wilson after that stroke?

He became, at times, very rigid about any thought of compromise.

This is where you get into the historians and scholars arguing about this. A number of them see that rigidity and go, “Aha, that’s the real Wilson.” I don't agree with that. I see a man who could be very flexible, willing to go in for give and take. He did have tendencies that way [toward rigidity]. There's no question about that. He also knew it, and worked to counteract that. I think the major psychological effect was that after the stroke he didn’t have those “guardrails” to keep him from getting too rigid.

Evidently the effect of the solitude was that he remembered being out on the tour where he attracted big crowds and lots of applause. And in his solitude, it gave him the — I'd say delusion — that the country was with him and that he could carry this off.

It is quite true that he became the biggest barrier to compromise. There might have been — might, I would say might — have been some kind of compromise with some of the senators so that we could have gone into the League of Nations with reservations. There's more to it than just Wilson being stubborn, of course. But that was a major psychological change.

And then, when you talk about delusional, he at various times thought of running again for president.

Right up until the convention in 1920?

Yes. And not only then. In 1924, just before his death that year, he was already planning a run for the Democratic nomination, and even outlined some planks for a platform. One of his collaborators on that, by the way, was one of the three men he appointed to the Supreme Court, his most distinguished appointment, Louis Brandeis. Brandeis drafted some of these planks for him too.

Wilson’s attempted run before the 1920 convention was something that Mrs. Wilson, [Wilson’s private secretary] Joseph Tumulty, Dr. Grayson, Senator Carter Glass, who had just been Secretary of the Treasury, all had to work to quash. Wilson had appointed Secretary of State Bainbridge Colby, who was not a very distinguished appointment and frankly something of a yes man to Wilson. Colby had plans, Wilson said, to stampede the convention in Wilson’s favor.

Grayson rode down to Union Station with Senator Glass when he was leaving for the Democratic Convention in San Francisco, and stayed on the train until it was pulling out, basically instructing Glass: “Smother this thing. He is in no condition, absolutely no condition for this. This has to be stopped.”

I know “delusional” is a loaded term, but there it is. Now, what you also have to remember is that he wasn't always that way. He had mood swings. He had better days and not-so-good days. But he was not fully functional as president. He simply was not.

I want to get into that period of his presidency, but I have here the Pulitzer-winning interview that Louis Siebold did with Wilson, published about 10 days before the convention. As I understand it, there's a lot of fiction in that interview, basically suggesting that Wilson was the paragon of health.

Well, let's say spin rather than fiction. Siebold was one of two or three star reporters for the New York World, which was the leading Democratic paper in the country, and was as distinguished as the New York Times. I've done research in this era, and I've used both of them, and often the political reporting in the World is better than the Times.

So obviously Siebold was very sympathetic. And it was stage-managed, very much. By the way, that's not the only stage-managed thing. After he suffered the stroke, the White House spokespersons, Dr. Grayson, etc, never, never used the word “stroke.” They said it was “nervous exhaustion,” that kind of stuff.

Well, obviously, nature abhors a vacuum, so all kinds of rumors started circulating, including that Wilson had gone mad. “You see those bars on the White House windows? You know why those bars are there?”

For Teddy Roosevelt's kids, right?

That's right, for their baseballs, you had to protect the windows. Anyway, what the Senators did was, the Foreign Relations Committee cooked up an excuse to go see Wilson. Stuff involving troubles in Mexico.

And this visit from the senators to the White House was about two months after the strokes?

Exactly, in early December.

So for two months prior to this visit, was there no interaction between Congress and the president himself?

Just once, before the League of Nations treaty came up for a vote at the middle of November 1919, the Democratic leader in the Senate, Gilbert Hitchcock of Nebraska, got to see Wilson. And Wilson gave the orders: “No compromise, not with the Lodge Reservations.” So the treaty failed.

Anyway, they cooked up an excuse for two senators to come and see Wilson. The newspapers dubbed it “The Smelling Committee.” In other words, they were going to smell him out. The two of them were Hitchcock, the Democrat, and Albert Fall from New Mexico, a Republican, later Secretary of the Interior. The two of them sent the request and they figured, “They're going to stall us,” Instead, they got an answer: “Come this afternoon.” So they did.

Now, this was really stage-managed. The accounts differ over the bedroom’s lighting: some say it was in the shadows, others say there was plenty of light. They had Wilson in bed, with the bed covers covering his left side, the paralyzed side. He was next to a bedside table, which had documents on it, and he reached over at one point and referred to the documents as if he had read them, which he had not. The whole thing was a snow job. It was stage-managed.

The cat got out of the bag, finally, in early February 1920, when Dr. Young, the urologist who had been there for the blockage, just casually said, “Oh yeah, well, he suffered a stroke.” That’s how it became public knowledge, although the White House never, never acknowledged it. Nobody from the White House ever used the word stroke.

But it was a terrible coverup. Not the only one, interestingly. Franklin Roosevelt was in seclusion for six or eight weeks in the spring of 1944. He was down at Bernard Baruch's estate in South Carolina, and the only public statement out of him at that time was a very short radio blurb about D-Day. And that's all.

So this is not the only time that we've had blackout curtains around a president.

Tell me more about Edith Wilson's role in all this.

Kristie Miller, who has written a very good dual biography of the two Mrs. Wilsons, his first and second wives, once said she considered Edith’s book My Memoir a work of fiction. There's a new book that I strongly recommend called Untold Power, which is about Edith Wilson, by Rebecca Roberts, Cokie Roberts’ daughter. I think Rebecca Roberts is the first one who tries to paint Edith in a good light. I think that's right.

Let's say — I'm not granting this — but if Wilson was not going to resign or be removed, and if somebody was going to act as a surrogate for him — those are big ifs, and I don't concede those — but positing those, Edith Wilson was the best-equipped person to do it. She knew his mind and his moods better than anybody else. From the time that he courted her, he had been sharing the secrets of state, innermost decisions with her, so she knew it better than anybody else. And if you ask, given these terrible circumstances, how does she do?

I think the answer is, not bad. Not great. This shouldn't have happened. Wilson should have resigned. There should have been some mechanism for at least temporary removal, which there wasn't. But she was in this position.

Now, the major criticism that's been leveled at her is that she put his health and his well-being above that of the country and the world. And she kind of says that herself in my memoir.

She acknowledges that, doesn't she? “I was thinking of him as my husband first and the President of the United States second.”

But, the other thing is, she knew his mind better than anybody else, and she knew what he would want, particularly those first weeks when he was genuinely out of it.

I mean, look, we've got President Biden right now claiming he will not resign. People can be very stubborn, even presidents, in that situation.

What Rebecca points out, and I think is well taken, is that Edith claims in My Memoir that she never made a decision herself, never usurped anything. And you know the line from Hamlet, “The lady doth protest too much.” What she does admit in My Memoir is that she controlled access of people and information to him.

Well, we all know, don't we, that he or she who controls access to the president to some extent is president. And that's what she did. By December, he's having more interactions, getting more information, and more people are seeing him. But not a lot. Again, we did not have a fully functioning president for those 17 months after the stroke. This was obviously not a good condition, not a good thing at all, and it was covered up. It's like Watergate. What's worse, the original incident or the coverup? Well, they're both terrible.

Tell me a little bit more about the day-to-day of Edith's managing of the president. Who was he seeing? Who was he not seeing? How was information traveling in Washington, given that the president was in seclusion?

For quite a while, the only people who saw him were his medical attendants, Mrs. Wilson, and the immediate family, his daughters. It was a very, very small circle.

As Edith says, when serious matters came, demanding the president's attention, she would often put them aside, and she said, “I didn't want to upset him.” An awful lot of stuff just wasn’t getting through.

When Senator Hitchcock finally got in to see him, this is mid-November before the Treaty votes, Wilson was surprised that Hitchcock told him it wasn't going to pass without the rest of the Lodge Reservations. Wilson wouldn't believe it. In other words, he wasn't getting the information. He was secluded. Those kinds of things just weren't getting to him.

That situation improved gradually and it got better. I'll give you an example though, of what he didn't know, starting in. Right at the end of 1919, the beginning of 1920, we get the infamous Red Scare.

Wilson did not know about it. At the first cabinet meeting, after the stroke, which was in April 1920, he turned to his attorney general and the architect of the Red Scare, Mitchell Palmer. He said, “Palmer, don't let this country see red.” Well, guess what? That's what Palmer had been doing all along. Just an awful lot of stuff that he should have known about was being kept from him.

How did the rest of the executive branch function?

It limped along. Part of this is, at least up till the stroke. Wilson is a very strong president. He's not a laid-back, easygoing one. But he does not fit our model of a strong president. Our model of the strong president, which I think has some problems with it, is based really pretty much on FDR and LBJ: somebody who is constantly getting his fingers into everything, often micromanaging, often bullying. Throw a little Theodore Roosevelt in there too. The problem with that model, of course, is that in these cases a strong president is defined as somebody who's pushing the country in a liberal, progressive direction. I don't think the model of a strong presidency has yet really contended with Ronald Reagan.

Wilson, he'd been a college president, and his leadership at Princeton, in Trenton as governor, and then in the White House, was generally collegiate. He gave a lot of room to his cabinet members. Sometimes his beliefs were not quite borne out. But he believed that he had people there who knew the duties and responsibilities of their departments better than he did, and that's why he had them there. They were all on long leashes. There was a virtue in that, in the sense that the cabinet members were used to running their own shops, and didn't need as much presidential direction, or you could say presidential interference.

But that's how it functioned. In other words, it functioned without a president. You had major strikes, the Red Scare: we muddled through, limped through. But no, it wasn't a good time. It wasn't at all.

Tell me about the people who did not have access to Wilson. I know the vice president was barred from seeing him until his final day in office.

That’s an interesting one. The vice president was Thomas Riley Marshall, previously governor of Indiana. Kind of a hack really, kind of a hack.

Why do you say that?

Well, you know what he's most famous for? Saying, “What this country needs is a good five-cent cigar.” In other words, not a very elevated sort of fellow. Now, actually, I think that's unfair to Marshall. Marshall represented a certain kind of politician who survived and thrived or got ahead in some really nasty factional politics. The big Northeastern and Midwestern states, in both parties, had vicious factions that fought each other. Certain politicians got along by letting people underestimate them, being amiable, and making themselves acceptable because the factional leaders hated each other so much.

In some ways, Marshall is an unsung minor hero. Several senators approached him about doing something to replace Wilson. Marshall would have nothing to do with it. Now, mostly the view is that he was scared of it. I think he was being honorable. First of all, they didn't know, particularly in those couple months after the stroke, what his condition was. They were getting these optimistic reports out of the White House that the president would recover and so forth.

And Marshall said, what they were saying is, “We'll stage a coup for you.” And he wouldn't have anything to do with it. I think Marshall did the right thing. Now, this thing might have been different if there had been a vice president whom Wilson respected and believed that he could pass the torch to, or could even temporarily cede responsibility to.

And that almost happened. In 1916, before the Democratic Convention, several prominent Democrats approached Wilson's intermediary, Colonel House, about replacing Marshall on the ticket, and they wanted to replace him with Newton Baker. Baker had been this dynamic reform mayor of Cleveland, who had recently been appointed Secretary of War, and somebody whom Wilson respected enormously. Before the convention, Colonel House approached Wilson and said, “How about this?” And Wilson said, “No, no, I can't spare Baker. The War Department's too important.” This was before we were in the war, but clearly it was a possibility and there was a military buildup already going on.

Well, House kept arguing. He said, “How about thinking of the vice presidency as something like a co-presidency?” And Wilson, a great political scientist, was intrigued with the idea, although he eventually said it just wasn’t the time for it.

But I really wonder what it might have been like if Baker had been vice president, if there'd been somebody that Wilson would have been comfortable ceding authority to.

Vice President Marshall said he would only assume the presidency if Congress explicitly passed a resolution saying the office was vacant. Why was Congress unwilling to do that?

First of all, Wilson had lots of support. And that would have been such a radical thing to do. The problem is, the Constitution is virtually silent on this subject. It says, “In the case of “inability to discharge the powers of the office,” the vice president shall assume the role. That's it. What are you going to do? It may have been an unconstitutional act for Marshall to assume control.

The 25th Amendment [ratified in 1967] supposedly takes care of this. I have questions about whether it really does. I don't think we could have a Wilson situation again, but that's not because of the 25th Amendment. The 25th Amendment is a very clumsy article. Somehow you've got to get the cabinet together unanimously with the vice president. Again, it's a provision for a coup: the Constitution can provide a coup.

If you get a vice president, he or she is in the role because of synchrony with the president. The Cabinet has been appointed by that president. The likelihood that they'll remove the president… that’s a real problem, I mean, yes, if there's some genuine, awful physical disability, maybe like Wilson, but the much greater danger is mental instability.

I think the main protection we have against invalid presidents being shrouded in a coverup is honestly the media. We have just become so used to the sights and sounds of presidents.

Again, I mentioned FDR in 1944, but the president actually going under the radar for six or eight weeks? That couldn't happen, because of the ubiquity of the media.

How did the Democratic Party handle Wilson's condition when it became clear he was still interested in running for and serving a third term?

The really powerful figures knew that this would not fly. Postmaster General Albert Burleson, Senator Glass, and Mrs. Wilson had to work to shoot it down. Wilson afterward got wind of that and was furious. Nobody got fired from the cabinet after that, but Burleson said there was just not much interaction with Wilson after that. Wilson never forgave him. But I think the party handled it responsibly.

After Wilson's stroke, Edith claims that the doctors pushed for Wilson to stay in office. What happened for her to make sure that he didn't attempt to serve another term? Was there a change in heart?

She — look, you couldn't live with him day in and day out and not realize what a wreck he was.

Another pipe dream of his, there toward the end of his life, was to go back into academia and found a new university. One of his former Princeton students, Raymond Fosdick, also worked for the Rockefeller Foundation. Wilson broached this idea to him, that Fosdick could get some Rockefeller money to do this. Fosdick, very gently, heard him out, and just put it on hold and never responded to it. But in Fosnick’s memoir, he calls this a delusion.

William McAdoo was one of the stronger candidates that the Democrats could have put forward in 1920. Wilson quashed him, because he still thought he could win a nomination, right?

Yes. McAdoo was Wilson's son-in-law. He married Wilson's youngest daughter — McAdoo was only seven or eight years younger than Wilson, so that's kind of age gap we're talking about. McAdoo definitely was the most dynamic member of the Wilson Cabinet, and, in some ways, the man who got him the nomination in 1912. It was a deadlock convention for a while, there were various advisors telling Wilson that he had to withdraw and so forth. McAdoo told him not to and kept working, really making the deals with the various Democrats to finally get Wilson over.

He was a real spark plug. No question about it. He and Burleson were the two political operatives in the cabinet. When Wilson needed something done or a particular vote, he would send both of them up to Capitol Hill to work on the Democrats.

McAdoo saw that as long as Wilson harbored these delusions of running again, he couldn't get in the way of it. Now what he tried to do in late 1923, early 1924, he visited Wilson to try to get his blessing for the 1924 nomination. Wilson wouldn't do it, he just stalled him off.

It seems like there's a black box about how decisions were actually made at some of these critical moments. We know that Edith was choosing what information the president saw, but what's your view on how much agency and authority the president had after his stroke?

Intermittent, very intermittent. As you said, Edith, for a while there, controlled what got to him. When things didn't get to him, he didn't make the decision. When things got to him, and some things had to, he made decisions, sometimes wrong decisions. I mean, the refusal to compromise on the Lodge Reservations twice: first there was the vote in November and then there was a second try in February and March 1920, and he shot those down too.

He also fired Lansing as Secretary of State and came up with half-baked reasons for doing it. I think Lansing deserved to be fired, he had been a very disloyal Secretary of State. But Wilson did it in such a way that it reflected very, very badly on Wilson.

You mentioned Colonel House a moment ago, who was at one point the president's aide to camp or closest advisor. Edith Wilson did not allow any of his memos or reports to be seen by the president after the stroke. Can you tell me a little bit about that?

Edith never liked House from the get-go. When Wilson was courting Edith, he shared a lot of stuff with her, including House's letters from one of his missions to Europe in 1915. What she objected to, and I think with some justification, was House’s awfully smarmy tone. House sought to serve, but he also sought to manipulate. He saw himself as the power behind the throne. He was an incorrigible intriguer, particularly within the higher echelons of the government.

He hated Josephus Daniels, the Secretary of the Navy, and was trying to get Wilson to fire him. Jonathan Daniels was Josephus Daniels’ son, and later both FDR's last press secretary and Truman's first press secretary. And he complimented me in a lovely nice letter for something I’d written. He said, “I want to congratulate you on continuing the unmasking of that devious son of a bitch, Colonel House.”

House also tried to undermine Tumulty. Really, it was just about anybody who could have sort of independent government stature with Wilson. In fact, interestingly, House succeeded for a while at the beginning, early in the Wilson administration, of blocking Brandeis from being nominated for the Supreme Court. House was away in Europe. When Wilson did nominate Brandeis and, uh, he wasn't happy about it at all.

Now, he could be charming. He smarmed the British Foreign Secretary, Sir Edward Grey. But no, House is a, let’s just say a problematic figure.

Last question for you, John. In the 1920 general election, Warren Harding won with the largest popular vote margin for a Republican ever. How much of that landslide victory had to do with Wilson's condition?

A lot. A lot. It was a referendum against Wilson, against all the things that had gone wrong. Inflation, the Red Scare, strikes, just everything. It was easy for Republicans to blame anything on Wilson.