Today we talked to Alex Jutca; he leads analytics and technology at the Allegheny County Department of Human Services, where his team’s mission is to build the country’s leading R&D lab for local government. Allegheny County is known for having the best integrated data of any state and local system in the country, and they’ve applied it effectively, like using predictive algorithms to improve the county’s Child Protection Services.

We discussed:

What issues are consistent across Pittsburgh, Philly, and Baltimore?

How does a local CPS actually work?

When shouldn’t you involuntarily commit people with severe mental disorders?

Why has anti-addiction drug development stalled out?

Thanks to Rita Sokolova for her edits to the transcript. All data from Alex Jutca.

For a printable transcript of this interview, click here:

Alex, you work for the Allegheny County Department of Human Services. Allegheny County includes Pittsburgh, PA and its suburbs. What kinds of problems does the county face, and how does it compare to other similar cities?

One of the coolest parts of working in local government is that although you're only serving a delimited number of people, the universality of the problems creates an opportunity to build evidence and solutions that scale nationally. You could have differences in terms of the exact composition of refugee populations or in the composition of the drug supply, which present different challenges to different departments, but at the end of the day, you have many common challenges. Figuring out how best to address child maltreatment, serious mental illness, and downtown homelessness and encampments is relevant across the nation.

What kind of substance abuse do you see in Pittsburgh?

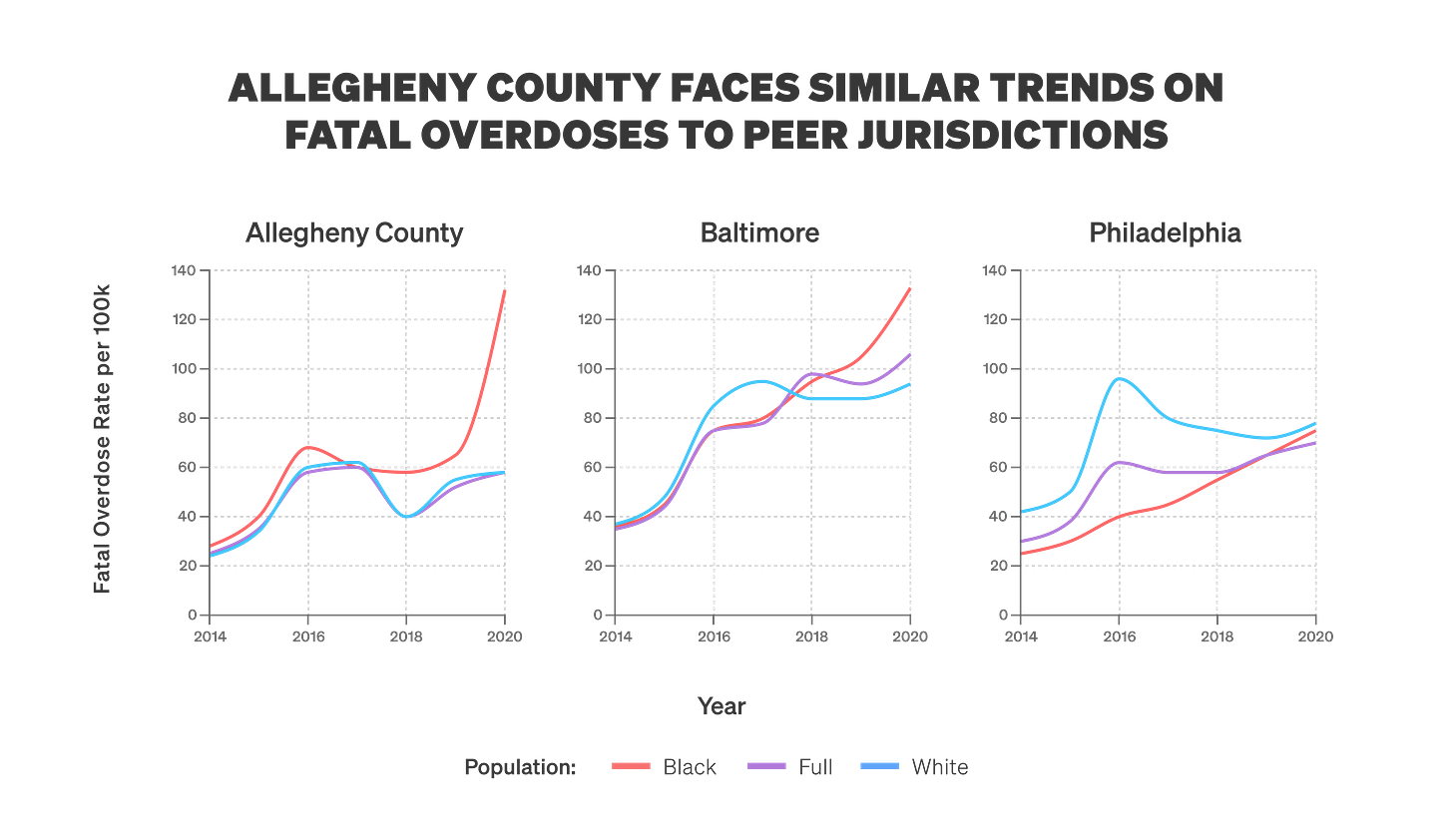

Allegheny County has an overdose death rate that looks a lot like that of our peer counties in Philadelphia and Baltimore, which you might expect: Because of our Rust Belt heritage, and the fact that the opioid epidemic washed ashore quite early in these communities. The through line is that the problems we deal with are not confined to the behavioral health system and private individuals. They drive a tremendous amount of criminal justice involvement and represent a disproportionate share of people who are booked into jail, involved in child welfare, or in homeless housing. Those problems have common underlying features, so we need to think about common drivers.

In a talk you gave at AEI, you mentioned that about one-fifth of parents involved in the child welfare system in Allegheny County are diagnosed with an opioid use disorder. Tell me about the revolving door of services here.

Allegheny County has a population of 1.2 million people, and we get somewhere on the order of 15,000 referrals of child maltreatment to our child welfare hotline every year. About half of those will be “screened in” for investigation. If we look among that group specifically, we see very high rates of indications of addiction.

What’s the difference between “screened in” and “screened out”?

In the child welfare system, there's a front door at which we first process referrals for children who are suspected of being maltreated. The initial decision that child welfare agencies face is whether to screen a child in for investigation or to screen them out. They'll call the person who made the referral to get more detail and seek to understand the history of the family. If call screening workers screen the referral out, that means that the agency has declined to investigate the family.

If the agency instead chooses to investigate that referral, we will send out child welfare caseworkers to conduct home visits and gather more information. In Allegheny County, we've developed the Allegheny Family Screening Tool (AFST), which is a machine learning algorithm that sits on the front door of that child welfare process. Deciding which of the 15,000 referrals to investigate is incredibly high stakes, and it can be difficult for call screening staff to make informed decisions. They might only get a brief narrative. The person who made the referral might have seen something that worried them, but they may not have the full story on the family.

It's also really difficult for humans to think in terms of risk. There's a great book by Philip Tetlock called Expert Political Judgment that discusses the limited ability of intelligence analysts to beat simple algorithms or generalist readers of the New York Times at forecasting geopolitical risks. We face very similar circumstances in child welfare.

[NB: We covered attempts to improve intelligence analyst forecasting in 2023 — see below.]

The screening tool’s algorithm tries to predict whether, in the next two years, concerns of maltreatment will rise to the level that a judge orders the child to be removed from the home. We use that risk score to help determine where to allocate scarce caseworker resources. We pair those risk scores with the insight of the call screening staff, so the model isn't a substitute for human decision-making. They work in tandem to make more informed decisions.

15,000 referrals per year is roughly 40 per day. Those referrals may come from neighbors, the preschool teacher, or someone on the street. Let’s say I'm working on the hotline at Child Protective Services (CPS) and I get a call from a preschool teacher worried about a kid in her class. What happens next?

Typically, we will start to fill out information about the victim child, family members, and the alleged perpetrator to get a more complete picture of the referral. We'll make additional calls to the referrer to get more information. That starts the downstream processes to get enough information to make an informed decision about screening a child in or out.

Tell me more about the Allegheny County Department of Human Services.

Our Department of Human Services has arguably the best integrated data system of any state or local agency in the country. We've had a two-and-a-half-decade run of using integrated data, which started with taking disparate government agencies that are siloed in many other jurisdictions and putting them all under one umbrella, creating the Department. Its operations include child welfare, homeless housing, and the behavioral health treatment system for Medicaid patients.

Bringing those systems under one umbrella agency enabled integration of the data. So suppose we see Santi Ruiz in jail: how do we know that Santi Ruiz is the same Santi Ruiz that we're serving in the child welfare or behavioral health treatment systems? Many of these systems are interdependent — they require coordination. For the department, data is useful for more than just the type of research people like me get fired up about. We use it to coordinate services and improve our clients’ lives.

There’s a saying in the tech industry that you “ship your org chart,” meaning that the way your organization is structured informs how you build your product. What's under the umbrella of the Department of Human Services?

We have five main areas: an aging office, an office for intellectual disability, an office that's focused on behavioral health treatment for Medicaid patients and the uninsured — behavioral health, for those who don't know, means substance abuse and mental health services — an office of community services that focuses on early childhood support, family strengthening, and homeless and housing services, and a large child welfare operation that investigates claims of abuse and neglect against children.

Most folks will assume that these bundled services are always under one department, but that’s not the case.

That's right, the organizational design issue is significant. In many other jurisdictions, those departments can end up like fiefdoms that don't cooperate very well, leading to challenges with data sharing. Getting lawyers from different county departments or local agencies on the same page can be quite difficult. By resolving that one org design issue, you foster collaboration.

To go back to child welfare, does the process in Allegheny County differ from what happens in other localities? Are folks in other counties unable to cross-check this data to see if the parents have been in jail or the hospital recently?

I don't know about the exact child welfare processes in other jurisdictions and what information they'll be looking at — My sense is that we’re unique in the sheer breadth of information and historical data that is available to us. For example, we can see educational information about the child, any cross-system involvement, or whether the alleged perpetrator was themselves in child welfare historically. That helps to build out a very rich understanding of the people involved in the referral.

So the CPS staff make their call about the risk to the child, and the Allegheny Family Screening Tool is simultaneously generating its own score, which may or may not line up with the judgment of the person taking the call.

That's exactly right. The discretion ultimately rests with the staff, who can override the default decision and decide whether a child should be screened in or should be screened out. That creates a check against these algorithms. There are things that it won’t pick up that might be gleaned from contacts with referral sources, for example.

When might a human screen in someone whom the algorithm says is at low risk, or screen out somebody the algorithm identifies as a high-risk case?

Some children might be at high risk of adverse outcomes, but the primary concern with them may not be child maltreatment — for instance, a youth who is at risk of juvenile probation involvement. That's the sort of thing that somebody might call child welfare about, but unless we think that there's a child maltreatment risk at issue, we wouldn't want to screen that in.

They may be at risk of all kinds of stuff, but not danger in the home.

Exactly. A low-risk scenario in which you might want to “screen in” is any situation where the historical data around a family doesn’t point to strong risk factors, but the specific nature of the allegations is quite substantial. There could be one-off events where something terrible just came out of the blue, for example. The call screening staff does that due diligence to make sure we're thinking about these things clearly.

What are the effects of using the Allegheny Family Screening Tool?

The concept of child maltreatment is sort of difficult to measure. Home removal is one solid indicator, because it requires a judicial process in which a judge ultimately makes that determination based on the child’s welfare. But people might be skeptical about whether child removal from the home is the right set of outcomes to look at, because those outcomes are connected to other system involvement, and the decision of a judge may be biased. We tried to think really deeply about those problems.

There have been a couple of evaluations of this work, and one of the initial studies on the tool offered some validation. For example, there are other indicators of child maltreatment, such as showing up to a hospital and needing services for injuries that are consistent with maltreatment. It’s hard to disagree that that’s a measure of something.

We measured predictions of home removal against hospitalization for maltreatment, and our comparison shows that those two predictions are very highly correlated. That gives us some comfort that this one set of harms does actually map to and correlate with other ways to think about maltreatment.

To return to your question about the impact of these algorithms, there are two different concerns. One is how the algorithm actually performs with out-of-sample prediction, which runs the algorithm on data that it hasn't seen before to prove whether it is accurate at forecasting what will happen to those individuals or those referrals. We’ve got a lot of data that gives us comfort there.

The other concern is the counterfactual world in which the algorithm doesn't exist, and determining whether we actually improve outcomes for children and families. We've got some interesting new data by Katherine Rittenhouse and her co-authors that looks at the introduction of the AFST and finds that, conditional on being screened in, it eliminates about 75% of the black-white gap in removal rates. The risk of these algorithmic tools exacerbating racial biases was incredibly politically sensitive and salient to those working in child welfare, but the researchers found some encouraging evidence that the tools actually eliminate bias.

That’s a striking example against the concerns about algorithmic bias.

Erin Dalton, who is our current department director, and our then-director Marc Cherna really spearheaded this initiative, and they and the team were proven out by the data. They took incredible pains to engage the community and hear their concerns and understand how best to incorporate that into the tool, wrote an RFP, got external researchers with impeccable credentials to come in and advise, and went through an ethical review. We've tried to make every analysis that we've done on the tool transparent, and it’s great to be validated after the fact. Erin and Marc and the team followed the right process steps here, which helped earn the trust of the community and staff to even implement this.

This is a pretty interesting dynamic in public policy: there was a very plausible story about algorithmic bias here, but when you went in with proper care and attention to detail, it just wasn't true.

There are certain circumstances in which building algorithms would be the wrong thing to do, but so many of these things come down to process and are somewhat empirical questions. There’s a playbook here that one could apply in different settings. That post-hoc measurement is incredibly important because if you see adverse effects, you have an opportunity to iterate. The public sector is really challenged by the fact that we don't have an objective function. If I'm an ice cream shop and I make terrible ice cream, I'm going out of business real quick. That’s not the case in child welfare. Crisp feedback loops help us see the impact of our decisions on the community and the children that we’re responsible for.

For those of us who did not study linear programming, what is an objective function?

It's the thing that you're trying to maximize or minimize within a setting. So in business, you’re typically trying to maximize something like free cash flow or profits, which provides a kind of North Star for what you're trying to accomplish, or at least one plausible measure of it. That doesn't exist in much of human services.

You guys built the AFST in-house, rather than following the more common model of bringing in outside contractors. Talk to me about the decision to build and maintain these systems internally.

Yes, the tool uses our data and is owned by the Department of Human Services. We had solicited external help with development and gotten some competitive bids because we wanted the best available expert guidance on developing this algorithm the right way. But the department has put an emphasis on building internal state capacity, so we decided to do it ourselves. We have a 40-person analytics team, a 10-person data science team, and a 10-person engineering team that's developing our own software now.

There’s a lack of skill complementarity between internal government folks and external advisors, consultants, and vendors, and the ambition can be incredibly lopsided, which can lead to slower delivery and much lower quality software, data science, and analytics. That can be the result of the agency not taking control or adequately specifying the vision and how it wants to use the tool. Not hiring internal staff can seem like a more efficient use of government resources, but it becomes costly in a million different ways.

The Department of Human Services also serves folks with serious mental health issues. There are one million annual involuntary commitments for psychiatric or medical treatment in the US, many of which I assume are repeat patients. Who is being involuntarily committed? How does the population that you work with compare nationally?

Every US state has a law that is designed to help individuals who are at risk of harming themselves or others receive treatment. Over the last couple of years we’ve focused on what's going on with this group and how to improve their health outcomes downstream. This has been one of my favorite projects because you very rarely get to see the end-to-end picture of describing what people are going through, identifying the underlying causal mechanisms, and proposing some solutions.

A couple of years ago our team decided to take a deep dive into this data. We looked at things like this group’s labor market outcomes, their medication adherence, and their mortality rate. Allegheny County might be the only place in the country where you could pull this type of analysis off.

One of the disturbing findings of this analysis is that there's an 8% mortality rate for these individuals in Allegheny County one year after being examined for involuntary hospitalization. If we look at the mortality rate on an age- and gender-adjusted basis for people who are coming out of our jails or who are going into homeless shelters, or the general population of low-income individuals in the county, this rate far exceeds that. Everybody understands that individuals with serious mental illness might have higher mortality rates, but we were able to put a specific number on it and show that it’s not a conceptual problem.

Now, that's a credit to our Chief Data Scientist Pim Welle, who fleshed all of that out. The data shows that clinicians view risk quite differently and have different propensities to actually involuntarily commit people. Those differences present an opportunity to study the extent to which those poor outcomes are caused by the involuntary commitment. Some people think that involuntary hospitalization is incredibly disruptive and traumatic and not very effective, and others think that there is no other way to get someone help but forced psychiatric care. Pim and our research partners Natalia Emanuel and Valentin Bolotnyy found evidence that involuntary commitment of people for whom different clinicians could plausibly make different judgments seems to actually exacerbate negative outcomes and increase the risk of harm to themselves or others.

If someone sees a clinician about being involuntarily committed, what are the odds that they will be committed, absent any other context?

The upheld rate for a petition averages around 80%, but it varies significantly across the types of clinicians. Psychiatrists tend to uphold at a much lower rate, which makes sense because they might be much more comfortable with the types of risks that they are presented with and distinguishing between a substance use problem and serious mental illness. Others, like emergency room doctors who might not have that psychiatric training, might feel less comfortable and uphold more of the petitions that they see in a given year.

The 80/20 rule applies in so many places. Your colleague Pim has a thread about how the people who are getting involuntarily committed account for 25% of behavioral health spending despite making up a tiny fraction of Medicaid enrollees.

I think every jurisdiction in the country wants to know what to do about this “frequent utilizer” problem. Most take a top-down approach that tries to identify the patterns that lead to something like frequently coming to the emergency room.

We came across this data organically and found that the 5,000 people in Allegheny County who are being involuntarily committed represent about 2% of our Medicaid population. Yet they’re 25% of our behavioral health spending on Medicaid. If we really want to bend the healthcare cost curve and improve behavioral health, we need to find better solutions for that group, which in turn addresses welfare concerns like their mortality rate and criminal justice involvement.

I won’t ask you to solve the mental health problems in the county or the country, but what kinds of solutions do you look at?

This is where going from problem identification and description, to identifying causal mechanisms, to designing a solution is super powerful, because you’re putting all the pieces together. We understand that this is a high-acuity group and that the way that we're doing involuntary hospitalization is not benefiting them, so we asked what we can do about it. One thing that the data shows is that medication adherence, which is a keystone to good care for individuals with bipolar disorder or schizophrenia, is incredibly low.

Isn’t it around 20%?

Yeah, it’s about 20% both before and after hospitalization, which is a good indicator that these people aren't getting connected to care effectively. This presents us with the challenge of finding mechanisms that could lead to higher adoption of behavioral health services. One thing that seems to be robust across jurisdictions is the use of financial incentives to encourage the adoption of different behaviors, but the literature around medication adherence is incredibly bleak and shows that it’s very context-specific: something that works in a developing country may not work as well in a richer one. If you're already in a situation where your health has deteriorated, taking a daily medication can be incredibly difficult. What if I could give you a monthly injectable so that you have to do something just 12 times instead of 365? And what if I can tie financial incentives to encourage you to show up"?

I worked with some of our peer support specialists at the psychiatric hospital down the street, and when we spoke to individuals with schizoaffective disorder, many of them said something like, “It took me eight years and three involuntary hospitalizations to realize that it was really important for me to keep on my medication, and that I had to make the adult decision to do it even if I was going to gain 50 pounds,” which is a common side effect of those medications.

That’s a call to arms for us to speed up that cycle, because there is some utilitarian cost-benefit calculus that's going on there. It’s a non-pecuniary cost to the patient to show up to an appointment and to take on the risks of side effects, and it’s painful to get a shot. It’s not something that anybody looks forward to, but we hypothesize that it’s critical to the stability of their care. We're funded generously through Stanford Impact Labs, where we're now running a randomized control trial, which will be the first test of its type in the US that will study how people respond to financial incentives for medication adherence and how that then translates into better outcomes in terms of mortality, lower utilization of behavioral health system, better labor market outcomes, and so on.

What would constitute success for you? I’m assuming that we won’t achieve 100% medication adherence, no matter the financial incentives you tie to this program.

That's an amazing question. Most of the work in this space in Europe has found effects on the order of 10-15% improvements in adherence. We think that we might be starting with a more acute population, so hopefully the effect will be even bigger. Something like doubling the amount of people who adhere to their medication regimen would be great.

But this is the sort of problem where you have to pick the low-hanging fruit. To me, paying people is the low-hanging fruit. Some people will still be resistant or the treatment won’t work well for them, but that doesn’t mean we should give up on them. This is where rapid iteration cycles in government are super critical. You can't just be on this timeline where you say, “I'm going to try one thing and then pack up and go home.” You need to stack wins.

In an upcoming interview with an expert on policing, we spoke about Jordan Neely, who was killed on the subway in New York in 2023 and had long been on the city's list of 50 people most in need of help. It highlights the challenge of delivering services to a specific, remarkably small population of people, to help them and make sure they don't hurt other people. As you're saying, a 10-15% improvement or even a doubling would mean that close to half of those folks will no longer be off their medication. That's a big win.

That’s right. Some of it is going to be about picking the low hanging fruit, but we may also need to consider other mechanisms to encourage adoption of care. In Allegheny County, we’re opting into the state's Assisted Outpatient Treatment law, which is a way to get individuals who are deteriorating in their condition in community into care without needing to be involuntarily hospitalized first. The behavioral health treatment system often takes action once people have absolutely hit bottom, like somebody with substance use disorder who is seeking treatment for withdrawal management. They’ve lost their family and their job before they're willing to go into treatment.

Something similar happens with serious mental illness where people deteriorate to the point where they need to be involuntarily hospitalized. What if we could go upstream and offer support and care to individuals before that becomes an issue and leverage legal options to help them get treatment? New York City has been very innovative in this space, and I think it's something we have to continue to invest in and monitor.

Sociologist Peter Rossi described one of the challenges here in his 1987 paper, “The Iron Law of Evaluation and Other Metallic Rules.” He talks about the fact that social programs that are rigorously studied generally have disappointing results, and that there’s an iron law that the expected value of a net impact assessment of any large scale social program is zero. Do you agree that it’s really hard to build effective and measurable social programs?

One of my takeaways from working in human services for a few years is that if we took an index card and wrote down everything that we know to work really well, we'd have a heck of a lot of white space left. Some people are very discouraged by that, but in Allegheny County, we have the leadership, data, and community partners to become the country's leading research and development lab for local government and to quickly build evidence.

Part of what Rossi is getting at is that it's quite difficult to even stand things up for testing. It’s hard to find the right implementation partners and to achieve significant scale and efficacy. We have a world-class opportunity here in Pittsburgh to address challenges like serious mental illness. We've also got work in the pipeline around addiction where there are opportunities for us to innovate both the medications used for individuals with addictive diseases and the way that we deliver those services. I’m not discouraged or surprised by the challenge, and the failures help us to get closer to the solution by ruling out all the things that we know can't possibly be that important.

The Department of Human Services tackles a lot of famously difficult social problems. Based on your experience with getting people into housing, mental health, child welfare, opiate addiction, and other substance use disorders, which problems do you think are most tractable and which ones are less so?

I love working in human services because we really do work on some of the hardest problems on Earth. I mean, they are incredibly difficult. Community violence is difficult. Child maltreatment is difficult. Addiction is difficult. It's hard to give a rank ordering among the impossible.

I have been particularly driven to increase the rate of innovation in behavioral health because there's a large number of individuals who are suffering, and there is an opportunity to do better. It's been 20 years since we've had new drugs approved for the treatment of alcohol use disorder or opioid use disorder. There is still no FDA-approved medication for individuals who are addicted to stimulants. Recent developments, like injectable formulations of existing medications, have been incredibly important but incremental. In order to get out of the situation that we're in, we're going to have to innovate on treatment efficacy and treatment delivery, or we're at risk of just watching the addiction problem burn out. I don't think that's something anybody wants to see.

To define terms for folks: an addiction “burning out” means that enough addicts die from their addiction that it's no longer a problem in the numbers.

Right. That’s what's happened in this country with alcohol use disorder, where it's a background hum of suffering and despair that has tremendous cost. But we haven't raised the federal alcohol tax in three decades, and there hasn’t been much policy or drug innovation there. I worry deeply about capitulation to opioids, and we’re seeing some worrying signs that this cycle may be repeating in sports gambling, although less fatally.

The National Institutes of Health funded a $350 million, four-state, 67-county randomized controlled trial called the HEALing Communities Study, which used the best evidence-based strategies that behavioral health experts have available for combating opioid use disorder, and they found null results. That means they didn't find results that were distinguishable from zero. Even if you take their point estimate at face value and ignore statistical uncertainty, it suggests something like a 10-15% drop in opioid overdose deaths. We would still take that as a win, but it’s clear that the strategies that we have been pursuing aren't good enough.

You've been advising the Center for Addiction, Science, Policy, and Research (CASPR), with which IFP co-published an Innovation Agenda for Addiction. I want to flag a couple of projects that they’re working on — there's a Phase III clinical trial testing the effects of semaglutide on alcohol use disorder, and another experiment in Pittsburgh. Can you tell us more about that?

I've been really fortunate to partner with Nicholas Reville and his CASPR co-founder, Lindsey Holden, who have been total forces of nature here. Nicholas wrote a Substack post calling for an Operation Warp Speed for addiction. I think he was responding to some of the nascent evidence of GLP-1 drugs working for addiction. For people at home, the GLP-1 drugs are blockbuster hits like Ozempic, Wegovy, and Zepbound. They have been found to curb food noise, and are showing signs of curbing other kinds of craving and addiction. I've been working with CASPR on a traditional Phase III clinical trial.

We have another public health-focused trial that would introduce this drug to people in high-acuity states, like individuals who leave the jail with alcohol use disorder. This group has a two-in-five risk of going back to jail within a year, and they have poor health outcomes. Addiction is a major driver of criminal justice involvement, and if these drugs could be effective for that population, it would be a total game-changer for society. Reasonable people can disagree on whether or not that will happen, but I think we need to try to seize the opportunity as quickly as we can.

In Pittsburgh, our unique healthcare resources and ability to weave in administrative outcomes, which is rarely done in these types of trials, let us do something incredibly important. We're talking to some great philanthropic partners who are interested in supporting and we're hopeful about getting that off the ground this year.

There's been a big federal-level push for government efficiency these past few weeks. How do you think about the county-level version of government efficiency? The Department of Human Services runs the mental health housing system, and the local paper wrote about how the department was providing housing for around 500 people at a total annual cost of over $40 million. That’s over $80,000 per person per year for housing alone for people with serious mental health issues, who are also often also getting county-funded treatment and other help. How did you think about bringing that number down?

We always want to scrutinize the way that we're using our funding to make sure that it's going to the highest-value uses. We need to constantly revisit how services are priced, whether they’re in line with actual costs, and where we can gain efficiencies, such as using Medicaid to fund services. Budget constraints have driven our interest in using that funding well, and our director has spearheaded an initiative to ensure that we’re right-sizing these contracts while individuals are getting the right mental health care and supportive services and staffing levels are appropriate. Those sorts of decisions sometimes come with short-term pain to providers, but we’re interested in pricing efficiencies so that we can reallocate funds to serve other people in need.

You see some interesting incentives in some of these systems. For example, if you have flat pricing for a given service but people differ in cost to serve, then you start to give providers incredibly strong incentives to take the lowest risk and least costly to serve individuals. They don’t do that because they're nefarious or trying to game the system. It happens organically over time if incentives are not managed well. That's where algorithms and tight management really come into play.

You came from the tech industry and joined a department that’s already one of the best in the country when it comes to data management and thinking from first principles. As Tyler Cowen would ask, what's the Allegheny County Department of Human Services production function?

It has been a combination of great infrastructure and partners and really strong culture, especially at the leadership level. You can have the best data in the world and really great talent, but if your leadership isn't willing to take some risks or make decisions that may not be politically popular, you won't make as much progress. Marc Cherna and Erin Dalton thought about data in bold ways, which has been incredibly empowering. When I came into the role, I said, “You guys have done this so well, why not double or triple down on it? Why rely on anybody externally? Just hire world-class researchers and engineers to come work for you.”

I've been blessed to get that buy-in to build out the team. Pim has done an awesome job of taking that baton on the data science side and building out a machine learning team with economists, and they're really speeding up the research production function. His tech counterpart Rachel Silver has built out an engineering team. This allows us to save costs while also building high-quality software.

We'll always have an important relationship with external academics and vendors, but we’re enjoying building internal state capacity on top of DHS’s incredibly rich legacy. Jen Pahlka has highlighted that capacity matters a great deal at the federal level, it does at the state and local level too. To echo Justice Brandeis, state and local government is a laboratory of democracy where we can iterate on a lot of really important social problems.

When predictive algorithms were introduced in these contexts in the early 2010s, a neutral observer might have expected that they'd be far more common across sectors because of the clear wins and improved outcomes.

So why don’t we see more adoption of these algorithms at the federal, state, and local level? Are you optimistic that that’ll change over the next ten years?

People often reach out to the Allegheny County Department of Human Services because they want to talk about integrated data and ask my boss Erin about how she built the data warehouse. What’s interesting to me is that people quickly get into the technical details without asking a more fundamental question about the departmental leadership that's really enabled this to flourish. Some of our success is due to the uniqueness of the data warehouse and having administrative data, but that's often a poor excuse. Many jurisdictions could build totally capable data science and algorithmic operations using the resources that they have. There could be technical skill gaps there, but it often comes down to culture and desire, and we have not had that at a large scale. Our department is interested in not just solving problems for our clients here, but also building a movement to solve national problems and build state capacity.