How the Government Loses a Road

"Nobody ever won awards by making their budget smaller"

This month, Statecraft focuses on America’s attempts to build nations in Iraq and Afghanistan. We think these stories are a great opportunity to get a closer look at what we mean by “state capacity.” Massive stateside bureaucracies attempted to build new, stable institutions in foreign countries. How did those bureaucracies perform? How about the institutions we built abroad?

Over the next four weeks, we’ll talk to people who saw failure firsthand in Kabul, Kandahar, and Baghdad, as well as people who encountered it at home, in Washington’s own institutions.

Nation-building in Afghanistan relied heavily on contracts managed by the United States Agency for International Development, or USAID. The agency oversaw road and school construction, infrastructure electrification, attempts to end the opium trade, and an array of other initiatives. Put bluntly, many of these initiatives were failures.

Kyle Newkirk joined USAID as Deputy Director of Procurement for Afghanistan, managing a portfolio of infrastructure projects and agreements. In today’s interview, he breaks down exactly why USAID struggled to achieve its grand goals.

What You'll Learn

Are anti-terrorism funding provisions actually effective?

Who takes on project risk?

Why were rotations in Afghanistan so short?

How did civilians end up carrying out active duty responsibilities?

For a printable transcript of this piece, click here:

You were the deputy director of procurement in Afghanistan. Who were you working with?

You're usually located at the embassy, no matter what part of the world you're operating in, and you're broadly under the ambassador, but you’re an independent agency there. A USAID location in a foreign country is called a mission, and you have a mission director, who runs everything and reports both to the ambassador and to USAID back in Washington.

There’s an administrative staff, and various programmatic offices: somebody who runs the ag portfolio, someone who runs the civil society portfolio, the economic development portfolio, etc. Depending on the mission, some are smaller, some are bigger. Some people wear multiple hats in that area.

Then you would have a series of both local contracting hires, and sometimes one or two American direct hires, depending on the size of the program.

So I was the junior procurement dude. The procurement director is the head contracting man or woman for the mission. That person usually reports either to the deputy mission director, or the mission director.

The director is the head contracting position for the entire country, or in some cases a region. They would have one or two deputies. In some big missions, like Cairo, there might be more than a couple deputies, but usually the deputies would manage a certain portfolio of practice areas. You might have ag, education, and private sector, and somebody else might have construction and governance.

But in your case, you were the deputy for all of them, or you had a particular place?

Yeah, I was the deputy for all of them, at least at the beginning, because it was pretty small and we were rotating in and out. It grew a lot over the years.

How long were you there?

I was in and out of Afghanistan for about 18 months. My role was odd because I was responsible for Afghanistan, but my duty station was actually in Bangkok. I would go in for four to six weeks, with one or two-week breaks in between.

After 9/11, there was a surge in demand for mid-career folks. I had been working on supply chains in the private sector but had wanted to get into the Foreign Service for years.

Because I did procurement in my normal life, they had me come in as a contracts and agreements officer. After I finished my training, they told me about a short term assignment. I had to go to Afghanistan the following week. This was early 2003, about a year into the Afghan war, and Iraq had already started. I flew to Kabul on a UN flight, got picked up in an armored Suburban, and whisked to the embassy by some Blackwater guys. It was wild.

How did you solicit bids and contracts?

We were doing quite a number of requests for proposal, RFPs. These were the typical RFPs you see for contracts at the Department of Defense (DoD) or State.

There were a lot of authorities then for doing non-solicited contracts, grants and agreements, just because of the security environment. There were very few groups that had the capacity to work in those environments. So there was a broadened authority for those types of actions.

When I was there, they hadn't yet started a lot of the direct granting activity with local host governments. There was a lot of money that was either going directly to the government of Afghanistan, or there was work on joint tendering with global NGOs. The money was flowing through the government of Afghanistan with approval from the U.S. government. It was very complex.

How did local contractors in Afghanistan find out about Requests for Proposals (RFPs) that they could bid on? Were they listed on SAM.gov, in the local papers?

It may be different now, but at the time, it was very difficult to find local contractors to assign direct contracts from the U.S. government. We typically gave the contracts to U.S.-based prime contractors who would then go out and find local subcontractors. KBR or Louis Berger or Deloitte would also post them on their own websites and email their listservs about opportunities. But a lot of it would happen via a local tender process.

Some competitive grants and cooperative agreements were posted on grants.gov, and there were some inter-agency agreements. We would send money to the Army Corps of Engineers to do construction oversight, or to the United Nations Development Program (UNDP), the World Food Program, WHO, things like that. We also took some unsolicited proposals.

What was the rough breakdown, the pie chart, of types of contracts you managed?

I would say 50% of what I managed were contracts for economic development and agriculture with big U.S.-based contractors, guys like Chemonics or DAI. There have been a lot of acquisitions in this space so some of the names may have changed.

About another quarter of the money I oversaw went to refugee resettlement and some reconstruction efforts with UN organizations like the International Organization for Migration and UNDP.

The final quarter went into grants and cooperative agreements with U.S.-based organizations. Those spanned everything: building schools, which is in the education space but construction-oriented, building clinics, some agriculture programs, and Cash-for-Work.

We also worked alongside the State Department on small-scale road reconstruction, to try to decrease illicit poppy-growing infrastructure, things like that.

There’s a GAO report about road reconstruction that talks about challenges with the ring road we wanted to build in Afghanistan. In some cases, DoD officials couldn't identify the locations of roads they had funded. That wasn't your team, but how does something like that happen?

I think it's probably endemic to all agencies that were programming reconstruction money. As a country, we're not good at expeditionary development and reconstruction.

In all types of government contracting, the oversight really rests with the contracting officer and their delegated authority, the technical representative. When you multiply Afghanistan’s size, the lack of security, and instability made it extremely difficult to do program monitoring. Sometimes there was poor initial planning. Say there was a task order to build a 20 or 30-kilometer section of road. Maybe it came in with pictures, with an engineering design. The Afghan subcontractor likely provides the geolocation for it. Then the prime contractor submits it to the Contracting Officer's Technical Representative (COTR) or the contracting officer for approval.

It gets approved, the money starts flowing, you start seeing invoices, but because the environment was so difficult, there were many projects that someone from our government never visited.

Sometimes USAID would say, “Okay, we're going to give a bunch of money over to the Army Corps of Engineers to go out and check on it. They’re engineers, we're not. They've got guns, we don't. They can go out and check on all that stuff.” This happened in the DoD as well.

But there wasn't enough capacity. The Army Corps didn't have enough actual active duty folks or reservists that they could call up because Iraq was happening at the same time. They ended up bringing in civilians from the Pentagon or wherever they could to fill active duty roles. I ran into people that came from the New Orleans Levee Districts and things like that.

Everybody got super risk-averse. You had members of the State Department or civilians overseeing infrastructure, and if the reconstruction team did not have the military elements, the embassy would not approve you going anywhere because they were afraid you would get shot, kidnapped, blown up, and so on.

Another problem was the really short time on station. You had civilians coming out on temporary duty station (TDY) and they were there for maybe 90 days. Even the DoD and State department staff, USAID, ISAF or NATO forces that were in theater were probably only there on, maximum, a 13-month assignment.

If you factor in Rest and Recuperation (R&R) leave and vacation, out of 13 months you might've only had to be in country for 36 weeks or so.

Wow.

If you played your cards right.

The location of that road would just get lost because nobody kept the records. There were lapses in oversight because so many invoices came in, they were spending so much money, and people would just pay them without the right documentation.

Help me understand why folks had such short in-country cycles?

That is a great question. The civilian side of the government often ends up following the example of the DoD in these post-conflict, insecure environments. Whatever it is that the DoD is doing, everyone else does the same thing. And they had set up a system of rotating units in and out.

I think their perspective, rightfully so, was that this was a multi-year, multi-generational endeavor. This wasn’t a campaign where we're going to Europe to defeat the Nazis and just staying there until the job is done.

At the outset, after Tora Bora and running out the Taliban, they probably thought “Oh, man, this is a 30, 40, 50 year engagement.” But unlike going to Korea or Turkey or a base in the UK, you couldn't go with your family. So they got onto this cycle of one-year rotations. They had a really hard time attracting civilians to these posts, so they would offer more R&Rs and they'd pay for you to go away for a week. There was a big annual changeover of people, and you were just relearning everything again and again.

Given that sense that this was going to be a really long-term project, why did USAID and other agencies keep shelling out money for projects they couldn't oversee adequately?

With USAID in particular, nobody ever won any awards in the government by making their budget smaller. We would just think, “We will be better next year.” And, frankly, the Office of Inspector General (OIG) and Special Inspector General for Afghanistan Reconstruction (SIGAR) reports didn't really start until five or six years in. And so you didn't have an oversight mechanism within USAID for somebody to go, “Gosh, this is just not working.”

So you've got the institutional trajectory of, “If a lot of money is good, more money is better,” and nobody gets to the end of the fiscal year without spending every bit of money that they've got. Everybody was wanting to grow programs.

USAID is unique because unlike the State Department, which has a fairly large U.S.-side footprint, USAID has relatively few people in DC. Most all of the staff is in the field. You’re pushing through $18 billion in development funding annually, all of that is happening out there, and the infrastructure to actually provide centralized oversight in DC is lacking. The missions have an immense amount of autonomy in deciding what to fund, informed by what the mission director wants to push, and a little tied into who the ambassador is.

It’s all politics to a certain extent, right? Everything is really driven from the president down through the executive branch and depends on the administration. Everybody wants to show taxpayers the results, and they think, “More money will make it better and we'll be able to show more results.”

It’s not big enough and it's not sexy enough for congressional oversight committees to really dig into. They’ll bring the Secretary of State to the Hill to investigate foreign policy issues all the time. Hardly anybody's dragging the USAID administrator up there and saying, “Why can't you find the 15 roads that you built?” or “Why did you build 400 schools that nobody ever uses?” It’s big money, but it’s not very big money. Another thing is, it doesn't generate any domestic jobs, for the most part. It's not a base, it’s not a weapons program, so nobody cares.

I’m looking at the GAO and SIGAR reports, and they talk about the lack of upfront planning. They say things like, “The need for planning cannot be overemphasized. Audits frequently identify weaknesses in planning that impair the effectiveness of USAID programs.” Talk to me about some of those failures.

Yeah, I think that is generally true of the government's approach to foreign aid, and probably for any region or geography. There's very little infrastructure built into a USAID foreign mission or an embassy to develop even a one year strategic plan, or a multi-year strategic plan for our diplomatic engagement with a particular country.

We don’t have a 10-year development roadmap, it's all on 2 or 4-year cycles, really tied to our election cycles. And because we’ve been operating under a continuing resolution for the last decade, Congress isn't weighing in on what we ought to be spending money on.

The decision making is not strategic, it becomes extremely tactical. The programs that get funding largely depend on whoever the ambassador is or whoever the mission director is. USAID does not actually implement the programs, it’s a contracting organization.

To a certain extent, whoever’s the lead over these particular programs may decide, say, it’s really important that we invest in horticulture in Bangladesh. And maybe the new person comes into the agriculture program and they’re a small grains person, or a livestock person, and that’s the stuff they like to do. Let’s create some programming around that. Then they sell it up the chain.

At the end of the day, USAID doesn’t do any of the work they program the money for. We’re either hiring contractors or NGOs to go out and execute these programs. All that USAID really is, is a contracting organization that tries to funnel money into things that they think will possibly affect American foreign policy. Often the linkage between the programs and our foreign policy isn’t very clear. Every time you get new leadership, things can change.

And the contract periods are not very long. You would have massive infrastructure projects that need to be done, and maybe you were given a five year contract. Usually the maximum term is a five year contract and maybe there's an extension, but a huge infrastructure program, like building a dam and planning hydroelectric, just the design phase, site selection, and permitting that would need to happen takes two or three years before you actually get into construction.

So often when things don't get completed, it's because we're not actually taking a long enough view.

It’s surprising to hear that given that it seems like the global development field is now focused on measurability, asking “Does this replicate? How can we tell this money's having any impact?”

Based on your account, this was not really a priority for USAID while you were there.

No, I will say at least from a development practitioner standpoint, they are pretty serious about monitoring and evaluating development outcomes. “Did this thing actually work? What's the pathway to success if we do something similar?” I actually think the learning processes are pretty good and there’s been a lot of improvement over the years in driving programmatic design to get the desired outcomes.

Some of the bigger NGOs and USAID contractors actually have a really good track record of submitting a proposal that says, “Here’s what you should do versus the statement of work that you sent out, and here's why we think it'll work.” And they have a ton of data from similar projects in other countries.

When we shift priorities, like we did with Afghanistan, we have nothing to show for hundreds of billions of dollars spent.

Weirdly, Iraq has been a better development outcome than Afghanistan, even with all of the turmoil. I think the programs for Iraq were a little bit better designed, and, to an extent, we're still there, and so a lot of the work is continuing.

One example of an unbelievably successful multi-year commitment is PEPFAR. It has broad bipartisan support and has been amazingly effective. There’s the counterpoint example: a long-term, multi-administration commitment to something. It was a moonshot but they used data and kept doing program refinement and over many funding cycles. There are several other things that could be as successful as PEPFAR. [We interviewed Mark Dybul on PEPFAR's design in the first Statecraft interview.]

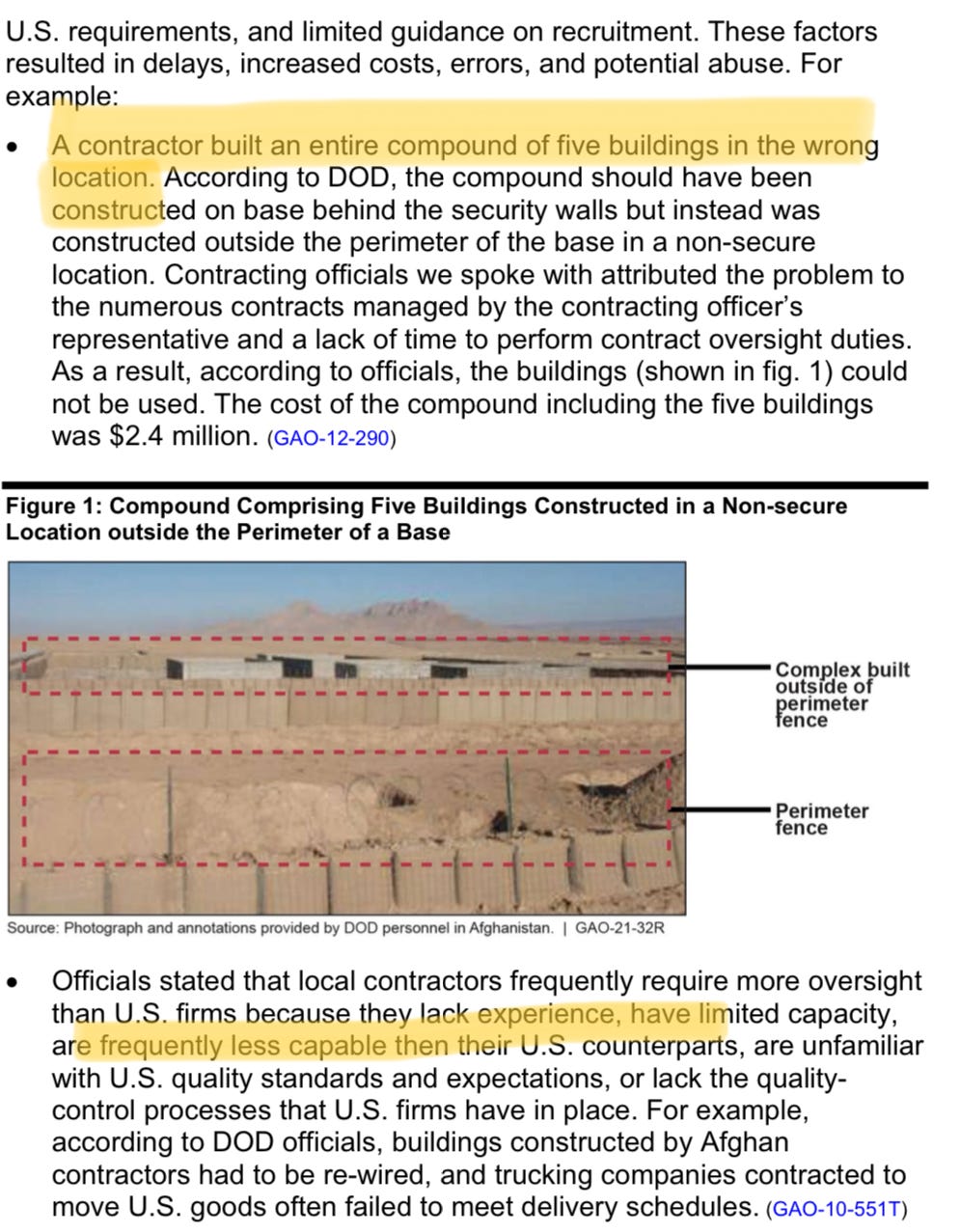

So far we’ve focused on the US side of this, but let me ask about the contracting environment in Afghanistan itself. According to one 2010 ranking, Afghanistan was one of the three most corrupt countries in the world. The GAO’s artful turn of phrase is that local contractors “are frequently less capable than their US counterparts.” What does that mean in practice?

Yeah. It's true that the quality of the work that we got out of domestic contractors in Afghanistan, and in other countries too, was not to standard, and the oversight left a lot to be desired.

The U.S. government sort of distanced itself by saying, “They’re a subcontractor, that’s the problem of the prime.” They’d claim to hold the prime accountable, but that was not well enforced.

Depending on the location of the project, your options for subcontractors were limited by whether you could guarantee security. You often chose construction groups or implementation partners tied to the provincial or local government officials, who in turn had other ties. The money that was allocated for security, a lot of that was being channeled back through the subcontractor. Once the money went from the prime to the subcontractor, it totally got lost. You couldn't track it where it went.

There was, frankly, a tacit understanding that sometimes those contracts were what it took to make sure your project could go forward. Some projects moved forward in a passively secure environment because of the contractor’s ties to the local government.

When you say “passively secure,” what do you mean?

That there wouldn’t be kidnappings or attacks on the workers. Sometimes there would be property damage, attacks or theft of equipment. Nobody liked that, but what we were really trying to protect against was attacks on the workers, or kidnappings. We might have had 2,000 “cash for work” workers on a road reconstruction project or a school building project, and a considerable number of expats in the field. We spent an immense amount of money on security contractors, and some were eventually exposed for corruption.

So some of the money gets passed back into the local warlord network as the cost of doing business in that region.

Yeah, it's the cost of ensuring security that got passed back into the network. We had all these anti-terrorism funding provisions. But if you signed a contract, you were personally liable for a construction firm in the host province, and there was no way that I could validate that they didn’t have ties to some warlord or Taliban group. So as a result the money just went to them as a subcontractor, through a prime contract.

Did the model of working with primes directly flow from those anti-terrorism funding provisions?

That’s a good question. The U.S. government has used the subcontracting model for a long time across many types of contracts, from DoD contracting weapons systems, to local industrial development, to helping pass money to women- or veteran-owned businesses, 8(a) programs, et cetera. So small business set-asides have to an extent always been embedded in US government contracting law.

But it became more important in post-conflict reconstruction because you had to use the local infrastructure networks. You were finding fewer and fewer capable Western prime contractors, and you had to use the local infrastructure networks. There was a lot of practicality around it, because maybe only local subcontractors had the necessary equipment in country to do that work. But it did shield the government from some of the more complicated issues on the ground.

The 2008 GAO report on road construction talks about the Afghan government’s inability to hold up its end of the bargain on maintaining roads, the DoD's inability to locate roads, and USAID's inability to fund useful road projects.

Obviously it’s easy for us to sit here now and say that nation-building in Afghanistan was a failure, but the 2008 report was already pretty damning. Why did we keep funneling American taxpayer money to multi-year projects that we knew were bad places to park it?

You're right. It was obvious that this wasn’t working very well by the second term of the Bush administration, but they were so invested in it that they weren't going to take their foot off the gas. When Obama was elected, it became, “Iraq: bad war. Afghanistan: good war. We’re gonna do the surge.” We had the surge in troops, but there was also a diplomatic surge, so more money, more foreign aid.

By the end of the Bush administration, they thought it would be someone else’s problem, and then Obama doubled down in his first term. They pared it back a little bit in his second term, but he was committed for eight years. So now you have 16 years of, “I'm not willing to say that my choices were wrong.” Until Trump, nobody really asked if it was working.

Then you got this amazingly idiosyncratic presidential administration that was really skeptical about what we were doing internationally. You wouldn’t have expected it, but they ended up asking a lot of the right questions.

From Bush to Obama, there was politics and inertia. It was just easier to keep doing the same thing than to ask difficult questions and do major course correction.

You’ve given some good reasons for suboptimal procurement. Could things have gone differently or were we always doomed to have rampant corruption and inability to locate roads and oversee projects?

I tend to be maybe more positive about this than maybe I should be. I think things could have gone differently if we had a clear sense of what we were trying to accomplish, a rational sequence for doing it, and, frankly, a lot less money. I think that when the money started flowing in during the surge, there was too much for the U.S. government and the implementation partners to manage, and the infrastructure for it didn’t exist.

USAID had been shrinking for years. There was a reduction-in-force (RIF) during the Clinton administration and they didn’t have the capacity to manage billions of dollars in a very complicated environment. The cadre of foreign service officers had shrunk.

If we had clear aims and a slower ramp and didn’t also have to manage Iraq as well, we could have prioritized what we thought were the key things, because there was so much to do. We were trying to rebuild the government, provide some stability and coalesce around Karzai, redo the banking system, redo land tenuring, build the ring road, the Kajaki Dam hydroelectric project, all at the same time. We undertook too much.

I think the ring road project was probably the right call, the whole country needed that interconnectivity. It probably would have made more sense to then focus on telecoms rather than reinventing agriculture far away from Kabul. And that would have allowed us to ramp thoughtfully.

Another part of the context is, when I first went into my training in February 2003, all of the organizational leaders were off planning for Iraq. This was as we were starting the biggest development initiative the US government had done arguably since Vietnam, and Afghanistan was already on autopilot. It didn’t have to be that way, right?

You mentioned the Kajaki Dam, which was a failed attempt to build a major hydroelectric dam in Taliban-held territory. Could you tell our readers a little bit more about the vision there?

Yeah. There was very little electric generation in Afghanistan. The idea was to retrofit the dam and put in a new turbine, and the added electricity would spur economic development. It would also give the Karzai government legitimacy by showing that it could build infrastructure that would make people’s lives better. It ended up being complicated, expensive, and mad.

[For more on this story, see Afghanistan Waste Exhibit A: Kajaki Dam, More Than $300M Spent and Still Not Done]

Was that another one of those cases where USAID just got locked in?

Yeah, it became the thing that had to get done. It became a political imperative, like, “We can't tell Washington that we failed.” We lost all perspective around what it actually meant for the development of Afghanistan.

If you went back to 2002, 2003, what advice would you give yourself? Would you have done anything differently?

Yes. There was still a lot of national unity post-9/11 and a sense of national service that we don't have today. It wasn't a golden era by any stretch, but we are definitely more jaded as a nation now.

What I would say to myself back then is, “The American taxpayer did not hire you to just push somebody’s political purposes. Be critical, ask better questions.”

I should have put a picture of Colville, Kansas, my hometown, on my desk to remember that those guys paid the taxes to get you here to do this, and you should ask how this benefits them. You get tied up in the power of the black passport, the prestige of a job in the foreign service. Don't lose sight of what a privilege it is to serve.

You came from and went back to private sector supply chain and procurement work. How would you change USAID procurement generally? Is there a magic bullet or a set of levers that you would pull to improve its capacity?

That’s a great question. Someone once told me the government budgeting and procurement process has a perverse efficiency to it: there’s a real rationality in how it works.

One thing I would say is, the DoD has chief acquisition officers who oversee agency acquisition strategy. I think USAID could benefit probably from more centralized acquisition, where what happens out in the missions is connected to an infrastructure in DC, and more in sync with State.

This is going to be absolute heresy to foreign service contracting officers everywhere because they value their independence. But we should be syncing USAID’s acquisition policy more closely with the Secretary of State and from the President all the way down.

USAID could learn from other agencies that manage procurement and acquisition well, like the General Services Administration (GSA) or DoD. USAID does not want to be seen as linked to DoD because we serve State, but there’s a way to still maintain field independence and take better advantage of new procurement vehicles. There’s been some pretty good innovation in this space over the last 5-10 years.

We just interviewed Rick Dunn, who pioneered other transaction authority at DARPA. What you’re saying dovetails nicely with his view, that people should be using these authorities much more than they currently do.

Oh yeah, a thousand percent. That's a good one. USAID’s tried to do some DARPA-esque things. But they haven't tapped into quite the right authorities around that.

Later this month:

How the CIA managed its Afghan bases

Building Iraqi government agencies from scratch

Does the State Department need more process?

Thanks to Rita Sokolova for judicious edits to the interview transcript.